Situated in the town of Vengurla in Maharashtra, a resident of Redi tells me that it is the last village on the coast of the state’s Western Ghats region. With a population of around 5,000 people or 1,650 families, Redi has also been a centre of iron ore mining in the Western Ghats.

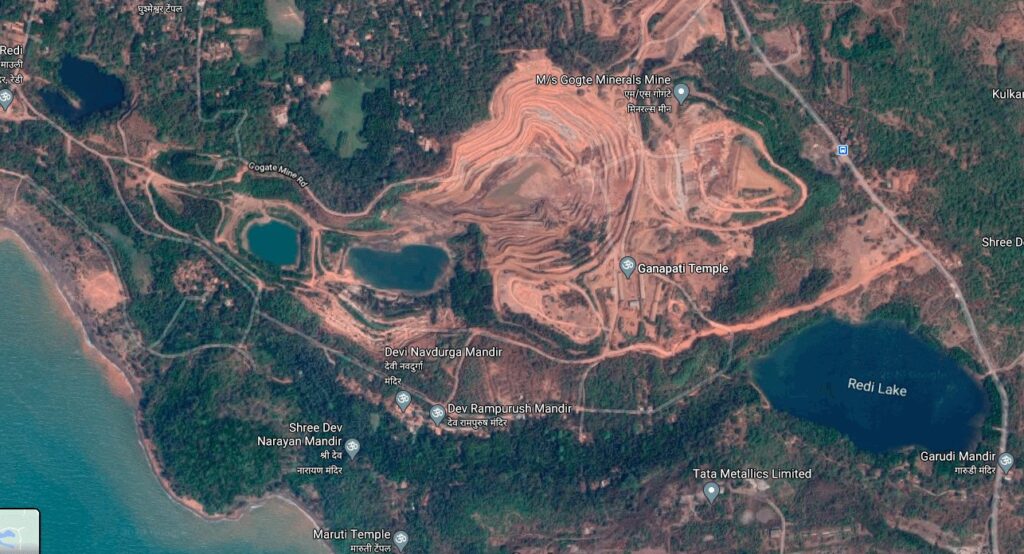

The topography of Redi’s mining region is undulating: the main ridge runs from east to west, sloping towards north and south, with the northwestern end of the mine ending in a valley. Mining in Redi began in 1950 and continued till 1992—due to the low demand for the low-grade ore being mined, mining activities were halted for 18 years before restarting in 2010.

The mine—spread over a private area of 94.706 hectares—is currently granted to Gogte Minerals with the lease validity lasting up to 2056. Mining activities are operated by Fomento Resources and Infrastructure Logistics Pvt. Ltd. (ILPL). The Redi mine practices open cast mining, post which ore dumps are created in and around the mining zones to store the extracted ore. Today, the ore from the Redi mine is largely exported to China through the Redi Port.

While humans have strived to enable development for national growth, it has ultimately altered our environments in its quest for both social and economic gains. As is seen in the case of Redi, it is important to outline the tradeoffs between development and ecological balance to leverage sustainable development.

How Mining Accelerated Redi’s Environment Decay

With the mining lease valid up till 2056, the ecological damage to the Konkan coast that the mine has unleashed is likely to worsen. This is a cause for concern as the Sindhudurg district in which Redi is located was declared an eco-sensitive zone in 1988. A biodiversity hotspot in the Western Ghats, the region is a habitat for many endemic species such as the Indian giant squirrel, an IUCN endangered species.

According to a resident of the village residing just 200 metres away from the mine, Redi’s environmental problems began in 1976: when mining took place below sea level. Today mining activities are carried out 50 metres below sea level which has altered the water table and groundwater quality.

A section of the leased mine lies within the Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ), at a distance of less than one kilometre from the Arabian Sea. Due to this close proximity, seawater has been seeping into the surrounding groundwater and freshwater mined pits. As a result of the mining, groundwater tables have also shifted.

While there is no direct dumping into the sea, the dumps of ore are found near the shore near Redi’s Ganpati Temple and in Kanyal. The water currents and ocean breeze carry the ore dust into the sea, polluting the surrounding pristine marine ecosystems. The mining silt that gathers on the shores has also impacted the beach morphology, dune vegetation, and the nesting grounds of various crustaceans. Local communities along the Konkan coast have been sustainably harvesting the many marine resources here using traditional fishing methods for years now. With the mining effluents draining into the Arabian Sea, villagers in Redi have observed depleting marine biodiversity. Over the decades, the continuous dumping of excavated topsoil from the mines near the Arabian Sea has also reclaimed about 34 hectares of land violating CRZ regulations.

A report by the Ministry of Environment, Forests, and Climate Change inspecting Redi’s mining activities further states that mining activities continued without obtaining environmental clearances to do so, violating the provisions of the Environmental Impact Assessment Notification, 2006. Additionally, as per environmental clearance norms, mining authorities have to undertake rehabilitation and reclamation of mined-out areas—and so companies have planted acacia trees around the mines and dumps. While the acacia trees are widespread and create an illusion of green cover, they have replaced native tamarind, java plum, kinjal, mango, and kokam trees, among others, which were habitats for the rich biodiversity of the Western Ghats. The acacia trees do not similarly attract wildlife. “There was a time before mining activities wiped out plantations and forested patches near the village when we used to see peacocks and other birds frequent our backyards,” says Govind*, a village elder. “Today, we see no wildlife.”

Mining has affected Redi’s built environment too. The village’s lanes and houses are covered with dust as tippers and dumpers pass through transporting ore from the mines to the dumping zones and the port. “Our houses are covered in dust all day,” explains a villager staying close to the Redi port. “When we sweep the dust off the floor, we can easily find the highest-grade ore particles.”

The dust covers plantations too, impacting their growth along with soil quality. “During the monsoon, the silt washes into nearby plantations leaving the land infertile,” explains Ramesh Kumar*, a resident of the village. “This leads to loss of farming activities in the village, with no compensation from the mining company.”

The Impacts of Mining on the Health of Redi’s Residents

Redi lacks the medical infrastructure required to treat the laundry list of health conditions its residents are facing as a result of mining operations, especially due to dust exposure and poor-quality drinking water.

Mining companies are expected to transport ore using separate roads that do not pass the residential zones of the village. In Redi, this doesn’t happen: the ore is carted from the mine through the village to the dumps and port. The mining company’s dumpers and tippers are also driven throughout the day on the ghat’s roads, which surround Redi. These vehicles do not follow road traffic regulations and are often rashly driven, causing accidents on local roads.

“As the tippers and dumpers filled with ore drive through the village all day, villagers are exposed to dust, further causing an increase in respiratory diseases like Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), recurring cold, and asthma,” explains a Redi-based doctor. He adds that for illnesses like COPD, general physicians prescribe steroid-based treatments which cause side effects like diabetes and hypertension in the long run. “Even though we understand the impact of mining on our health, we can’t oppose the activities because our livelihoods depend on it,” says a local shopkeeper and restaurant owner.

Moreover, as water tables in the village deplete, access to naturally available drinking water is becoming an alarming issue.

Water collected in the mines is pumped into a water treatment plant; the clean water is to be reused by the village. Yet, the water that villagers receive is still polluted, saline, and unfit to drink. So, they are dependent on the village wells for potable water. However, according to the residents here, the water quality in the wells has also degraded alongside the increase in Total Dissolved Salt (TDS) levels. Now, Redi’s residents are accustomed to boiling water to make it drinkable. Water from the treatment plants is used for daily chores like washing utensils and clothes. With the lack of access to potable water as a result of mining activities, cases of thyroid disease and kidney stones are also increasing in the village.

Mining Catalyses Socioeconomic Shifts in Redi

Most of the village residents depend on mining-related activities for financial survival: the mines operational at Redi directly hire over 200 villagers, as well as many village contractors who own and drive over 450 dumpers and tippers used by the site.

This financial boost has helped families improve housing facilities and amenities, with many shifting from earthen, tiled houses to concrete ones equipped with modern amenities. Many households now also own personal vehicles.

Yet, this employment is contractual and villagers fear losing it should circumstances turn. “Farming activities have stopped due to the loss of fertility in our lands,” said Sadanand Raikar*, a resident of the village. “There is no other source of income for the villagers of Redi but to work in the mines.”

Mining in the village has also brought with it the inflow of migratory mine workers. 30% of the drivers working on the trippers and dumpers hail from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh.

Through its CSR programs, Gogte Minerals used to sponsor educational programs for the school children, however, this initiative has been discontinued for the past few years. This supplementary education could have proven crucial to strengthening the village’s limited educational infrastructure: Redi has only five Zilla Parishad schools that provide education up till Grade 10. Students are forced to travel to neighbouring villages to receive higher education, while some even travel across state borders to Goa to receive a quality education.

“Now, people are educated and aware of the impacts of mining and do not want to work for the mining company,” Sushma*, a resident of the village says. “So, many are moving to Goa to explore better job prospects.”

The Future of Mining in Redi

Mining companies receive political support from Redi’s Gram Panchayat. It is for this reason that Redi’s residents expected the mining companies to support the village—yet, as we have seen, they are yet to be held accountable for the harm they cause to Redi’s ecology and its residents’ wellbeing.

For example, the 2020 pre-feasibility report for the mine states that the lessee, Gogte Minerals is in the process of obtaining additional land to dump waste and overburden (or the layers of rocks and soil that are removed in order to reach the ore). This land is to be annexed by the company from the Maharashtra government. Existing mining activities in Redi have already placed a huge burden on the environment: an extension of the leased area will most likely further degrade the surrounding ecology and biodiversity.

So, if mining is to continue for another three decades as per the lease period, it needs to be done sustainably: this involves understanding the tradeoffs between environmental degradation and economic benefits in the coming years.

For example, environmentally destructive mining once generated high economic outcomes as high-grade iron ore was extracted. However, with overmining in Redi, the ore extracted today is not of the same quality as found before, resulting in declining demand for it. All of this activity—for questionable economic benefit—is catalysing the numerous changes to Redi’s public health, environment, and economy. Given that the climate crisis is a reality, and the threats faced by the ecology of the Western Ghats and Konkan Coast, is continuing and expanding such destructive mining in anyone’s developmental interest?

Editor’s note: This article is based on the author’s in-depth study of unsustainable mining in Redi for their Master’s research.

*Names changed | Featured image: areas being mined in Redi, by Lourdes Sequeira.