A 60-year-old distressed Ranjan is lying paralysed on his cot, outside his home in the slums of Kota, Rajasthan. “I have not seen a doctor in three years,” says Ranjan. However, recently, to Ranjan’s relief, Arvind, a community health worker, reaches his home; he not only inquires about his health but is also able to measure the vital signs—pulse rate, body temperature, respiration rate, blood pressure among others. As Arvind enters the data on a mobile application, the application immediately flags the alarming 204/111 blood pressure reading, which prompts him to make a phone call to the doctor. “I found Ranjan in a near-fatal health situation when I was checking his vitals. It was alarming!” says Arvind, clutching his service bag.

Over the call, the doctor confirms to Arvind, the community health worker (CHW), that Ranjan’s blood pressure was indeed alarming and if not brought down, he was at risk of suffering another stroke. Emergency medication and blood pressure monitoring over the next couple of hours for every 30 minutes is prescribed. However, Ranjan’s family does not have a blood pressure monitor at home and are unequipped to monitor him. “I am from a remote village in Kota and have never got my medical condition checked,” Ranjan expresses. With a situation to handle, Arvind gathers other frontline community health workers to help him and arrange the medication from a local dispensary. They monitor Ranjan’s blood pressure every 30 minutes for the next five hours, routinely sharing the readings with the doctor over the phone. Gradually, over the next few hours, Ranjan’s blood pressure drops to an acceptable level. The on-ground intervention with the help of a centralised team of medical experts have averted a more than likely health emergency with the help of technology, popularly known as ‘telemedicine’.

The State of Telemedicine in India

Over time, telemedicine has become a new buzzword floating relentlessly in medical conferences, health discourses, and the startup landscape. The surge in telemedicine applications has revolutionised healthcare services by paving the way for remote healthcare technologies by adapting, modifying, and creating a phygital telemedicine model that works for some of the most vulnerable people.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Indian public health ecosystem has witnessed a paradigm shift to telemedicine, addressing the needs of harder-to-reach populations. The second wave of COVID-19 was devastating for India, with the number of cases consistently breaking world records. The situation became dire with rising cases, a lack of medical supplies, a rise in deadly fungal infections, and limited human resources to manage the burden. In addition, lockdowns had taken a big toll on livelihoods and the economy as a whole. Although the wave has abated and vaccination rates in the past months have increased. However, the trend in countries across the world indicates that spikes in viral transmission are still possible, especially with the emergence of new variants. Within this context, it becomes important to use the tools at hand and prepare for upcoming infection surges in the best possible way. One key tool at disposal is telemedicine, a surveillance and care tool that allows caring for communities that find themselves isolated and without access to quality care.

How Telecare Complements the Existing Public Health System

Lack of access to care and increased out-of-pocket expenditures (OOPEs) could be addressed through early diagnosis and treatment of ailments, especially in the hard-to-reach population. In places with remote health infrastructure, community members do not prioritise seeking care unless it hinders their daily wage work as reaching the nearest hospital would also result in loss of wage and costs incurred for travel. Due to this health-seeking behaviour, the ailments get diagnosed at a progressed level, increasing the OOPE and potentially reducing the quality of life.

A possible solution to address the lack of access to care is to introduce telecare programs, which have the ability to diminish geographical boundaries and give access to timely consultations such as the one received by Ranjan. Telecare has the potential to bring relief to an overburdened public health system, take pressure off unmanageable caseloads, and ensure timely response to the target population. What makes the telecare mode different and relevant now is its cognizance of the comfort and social determinants of communities while offering healthcare services. Call4Svasth is one such telecare model that goes beyond offering consultation to the individuals in harder-to-reach communities and enables a holistic system of care.

During the pandemic-induced nationwide lockdowns, India witnessed a surge in health-tech applications such as Practo, 1mg, PharmEasy, and more. There were also organisations that stepped into design applications to serve the rural populations and curate specialised need-based modules for the underserved. This has resulted in the adoption and acceptance of digital-led innovation in telemedicine initiatives by the government that have laid the foundation for a digital ecosystem. Telemedicine solutions were a godsend to many health practitioners who were looking for opportunities to serve the population but also keep the flow of income going during the pandemic. As the application of telemedicine services rapidly grew, in March 2020, the Government of India introduced a set of guidelines for the practice of telemedicine, which were prepared by the Medical Council of India in consultation with the NITI Aayog in an attempt to bridge the gap of accessibility and affordability.

Following the pandemic, the government has also laid special emphasis on the Telehealth ecosystem in India. Its two flagship programs for the same are Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission for accessing physical wellbeing support and a 24×7 tele-counselling program.

Central Budget for Telemedicine

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare has received an allocation of ₹86,200.65 crore [budget estimate] for 2022-23 which is a mere 0.23 per cent higher than the revised estimate of ₹86,000.65 crore in 2021-22. Allocation to the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare in 2021-22 was ₹73,932 crore, an annual increase of 7% over 2019-20. In 2020-21, the Ministry was allocated ₹67,112 crore at the budgeted stage, which has been increased by 24% to ₹82,928 crore at the revised stage. This increase is primarily due to an allocation of ₹11,757 crore for the COVID-19 Emergency Response and Health System Preparedness Package. In last year’s budget, finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman allocated ₹2,34,846 (FY 2021-22) to the healthcare sector. The allocation was more than double compared to the allocations made in the preceding year.

Why Does Telemedicine Usually Fail?

There are several reasons why telemedicine might usually fail, in spite of the guidelines and world-over experience. In India, especially in rural areas, it is important to understand the complexity involved in designing and implementing telemedicine programs. The design of the intervention and the application should be patient-centric so that it delivers real-time health solutions. It is fundamental to understand the pain and needs of the community, which can be done by working in collaboration while developing an intervention that paves the way for health equity. Here are some reasons analysed by Call4Svasth, a community-led integrated telecare program serving vulnerable populations in India, that show why telemedicine can fail or have undesired results on the ground but telecare exceeds expectations.

Firstly, the lack of contextual realities often impacts the quality of telemedicine. The importance of design and implementation of a rural-centric intervention has a direct impact on the ground. A well-designed and context-appropriate teleconsultation can make a significant impact in addressing the healthcare equity challenge in rural and semi-urban India. A nurse working with Call4Svasth says, “It is important to design interventions and offer solutions keeping community needs as the centre.”

Secondly, there is a need to acknowledge and factor in the existing gendered digital divide. “Women are not allowed to visit doctors, and this contributes to lack of information and awareness resulting in decisions about their [women’s] healthcare being taken by the male members of the family,” says a nurse. In South Asia, the women in rural households do not own a mobile phone; it is a shared asset amongst the family. In India, women are 15 per cent less likely to own a mobile phone, and 33 per cent less likely to use mobile internet services than men. In 2020, 25 per cent of the total adult female population owned a smartphone versus 41 per cent of adult men.

Reimaging Telecare For the People, By the People

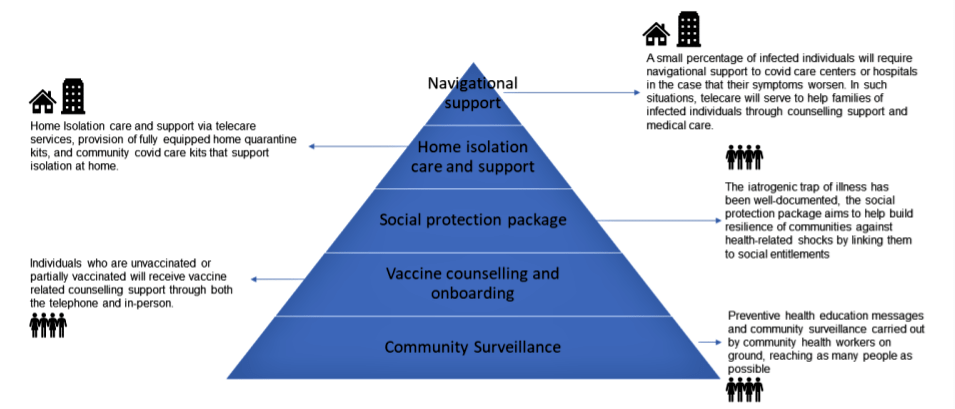

Telecare differs from traditional telemedicine helplines by virtue of its hybrid nature; the range of services it offers and the depth of its intervention. The name telecare consists of the three solutions it offers. Firstly, telemedicine as an access to medical experts over the phone; secondly, tele counselling as an access to mental health services over the phone; and thirdly, telehelp as an access to social protection schemes over the phone.

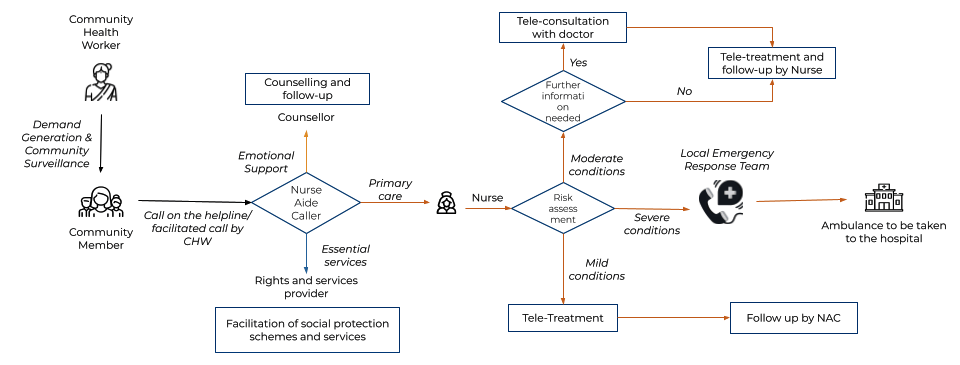

So far, telecare has successfully reached over 9,00,000 vulnerable households [across urban poor, rural poor, and other unique settings] as per the program estimated by Call4Svasth. Telecare can save time and money for rural communities by reducing the need for travel to receive care. Additionally, instead of depending on vulnerable populations to reach out to healthcare providers, the providers stay in touch with such populations without depending solely on smartphones through their community health workers (CHWs). While the care and counselling services are available through teleconsultation, the core of telecare is the feet on the ground, through frontline workers who generate demand and take care of localised delivery. While clinical counselling and care can be provided via telecare, frontline workers are trained to generate awareness.

Telecare is grounded in technology, using telephony solutions ,customer relationship management (CRM) and electronic health records (EHR) systems to effectively monitor and streamline caller support, bringing together the team of doctors, nurses, nurse-aide-callers and community health workers. It is an integrated digital platform with hyper-localised, community-led, cost-effective helplines run by trained nurses, nurse aide callers, counsellors, and social protection officers. The telecare platform extends holistic care through a telephonic model to address physical, emotional, and social determinants of health.

How Can Last Mile Delivery and Grassroots Involvement Be Achieved

Acceptance of telecare among the vulnerable population will only come along when there is a behavioural change in the community for which grassroots involvement is key. In the model designed by Call4Svasth, community health workers are recruited from communities where the program is deployed. The community health workers are salaried employees and are the face of the program on the ground. The training of community health workers includes using diagnostic devices like oximeters, blood pressure monitors, and glucometers to measure vitals. They develop empathetic communication, and interpersonal skills, learn to navigate the Call4Svasth app with ease and are equipped to handle emergencies. They are also the last mile delivery of the program and are instrumental in spreading awareness of the services along with facilitating the helpline calls in the community.

The community health workers are also solving the predominant digital divide—community members with little or no access to phones rely on the health workers to make calls. They also assist the community in operating phones to make calls, send old reports, and receive prescriptions. This has played a pivotal role in communities with high digital illiteracy.

In addition to training community health workers, other factors which require attention while designing a community-centric model are holistic care, continuum of care, and focus on health information. Physical and emotional well-being, access to health information and social protection schemes are all interlinked; addressing them in isolation is a temporary fix and does not ensure long-term care.

Crucial learning from the Call4Svasth program is that a system where the community members are the face of the program and advocate for it on-ground is more likely to succeed than a program with no local champion.

Through the interlinking of health services, Call4Svasth treats the members in accord with their complex ecosystem rather than treating each of their complaints in silos. This contextualises the service to the realities and expedites the adoption of the program in the communities making it holistic in its approach.

“My husband passed away during the COVID pandemic, and I have no one to look after me and my children,’ says Nagma, a widow from Anekal in Karnataka. Nagama had called the helpline to share her financial worries following her husband’s death. The social protection officer at Call4Svasth helped Nagma identify the widow pension scheme she was eligible for. For the next few weeks, the officer worked with her to avail of the pension from the relevant government departments. During this time, the officer recognised the emotional stress Nagma was experiencing and explained to her how a counsellor might be able to help her. Upon Nagma’s consent, the officer put her in touch with a counsellor.

In India, health neglect is high among the vulnerable population as it is generally not their priority. This, coupled with the utter lack of access to reliable health information, leads to a treacherous pattern of avoidable illnesses. Providing a one-time teleconsultation with doctors does not bring about the expected impact. The community members are not driven to seek a follow-up unless the consequences gravely affect their well-being and livelihood.

“I am clueless about what is happening to me. I go around the hospital which is impacting my livelihood and I don’t know what to do about it,” says Gopal, a vegetable hawker. In the Call4Svasth model, a continuum of care is provided for the community and people such as Gopal. The nurses follow up with those requiring medical attention and are provided with doctor consultations till their recovery progress is satisfactory. Every alternate day, those who are being treated are followed up by a nurse over a call at an agreed-upon time to check their vitals, symptoms and medication. If at any point in time the progress is not satisfactory, they are reconnected with the same doctor for a follow-up consultation. While expressing gratitude to the community health workers, Gopal says, “I did not know when I would be okay, but today I am happy that someone can understand what I am going through.”

During the pandemic, the continuum of care was crucial while treating COVID-19 positive patients when the health of seemingly healthy patients was deteriorating unexpectedly. The COVID-19 protocols in the Call4Svasth application tracked the patient’s vitals for 13 days; patients who seemed healthy but did not show the required progress from the previous day were flagged by the application and connected to doctors immediately to help in identifying potential emergencies early on.

Vulnerable and marginalised populations face the ‘burden of time’. The health systems usually chosen by the marginalised population create a burden of time since the facilities are overrun leading to poor access to relevant and timely health information. In the model developed by Call4Svasth, the health information-seeking individuals are given an equal if not more amount of time with the nurses or doctors to have their concerns clarified. By taking the time to inform the community about health, the agency is transferred back to them to take charge of their health. Having the relevant information and agency is the first step in changing the health-seeking behaviours of the community.

Take for instance the trans-people specific helpline, where frequently asked questions on hormone treatment, sex affirmation surgery, aftercare, and treatment complication are addressed. In absence of the helpline, the members earlier relied on word of mouth and quacks. By providing such information the trans community is better equipped to make empowered decisions. For any technology to work with the vulnerable population it requires to be simple to use and comprehensive. Keeping this in mind, the technology to support Call4Svasth was developed in-house.

India, a diverse country, has varied healthcare needs and the model developed evolves and adapts to these different community needs and resources. For initiatives such as this, the fundamentals of community-centred design are key. At present, the Indian discourse on successful telecare models is limited, but programs such as these are a step forward for bridging community-led interventions to address the gaps in treatment, access, and availability of healthcare services in low-resource settings.

Featured image is of a community health worker visiting a village; image courtesy: Swasti.