The ministry does not maintain separate data in respect of migrant workers who have died in road accidents during the lockdown.

That was the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways’ Minister of State responding to a question in Parliament about the number of deaths of migrant workers that took place on roads and highways during the first wave of COVID-19 in 2020.

40 crores. That is the estimated number of migrant workers in India. The Ministry’s response indicates how migrant workers are looked at by the State. Instead of malice or malintent, there seems to be confusion as to how to address the issues about migrant workers’ data. The fact that the workers are participating in distressed migration means the data point is moving across geographical areas. This creates a demographic which is dynamic, tough to track, and extremely vulnerable in its nature. The onus is on the State to address the vulnerabilities of migrant workers.

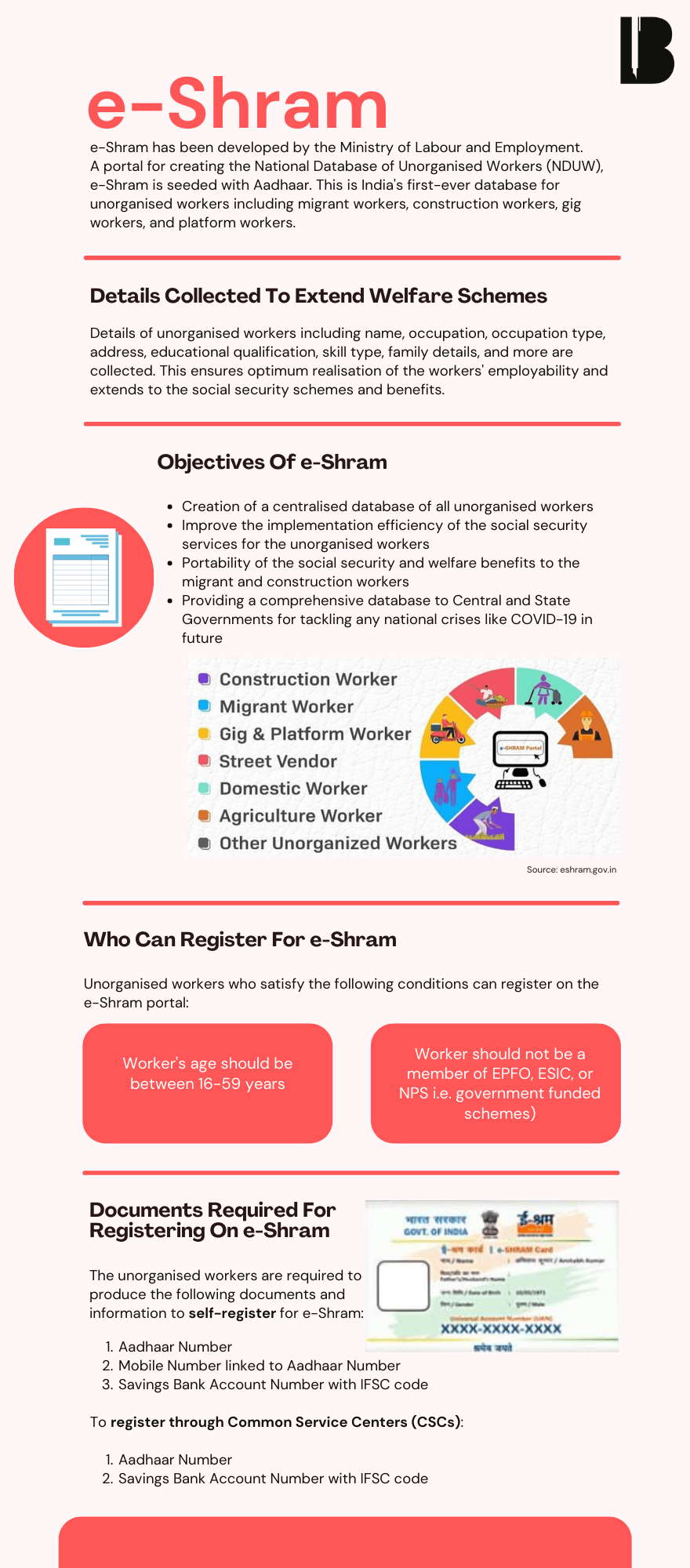

Steps being taken to tackle this problem are the wider implementation of Aadhaar combined with the new e-Shram portal that will be used for collecting information. Informal sector workers are disproportionately migrant workers. e-Shram aims to create schemes and policies that will provide benefits to workers in this sector, which is a welcome step after the migrant crisis of 2020.

The conversation around data protection in India isn’t resolved in terms of legislation yet. This leaves us with the question—how exactly will data be managed? Post the Joint Parliamentary Committee report on Data Protection Bill, 2021, critics argue that end users have weakened rights over their own data. It is important to look at the implementation of e-Shram and what data collection and storage practices it uses.

An ongoing study by Swaniti Initiative, an organisation working with elected officials to explore development solutions in grassroots India, looks at these questions. The study focuses on strengthening the social protection of the informal economy and of migrant workers across multiple districts in Maharashtra. It also recognises the need to move beyond data-informed policy design to a data-protected policy design. Collecting data and creating dashboards may not be enough. With special focus given to digital India, there also needs to be a focus on digitising government policies and services resulting in a shift to policy mindset.

The Difference Between a Data-Informed Policy and a Data-Protected Policy

Data-informed policies use data as the catalyst to create policies that understand the needs of the people. It provides services to people based on their needs. Data-protected policy elevates the person from a data point to a citizen with actionable rights over their individual information. The individual as a citizen is at the core of this idea.

How e-Shram Can Change The Way Data Is Used

e-Shram portal has a useful and quick self-registration page that requires three things to register as an unorganised worker—Aadhaar card, phone number linked to Aadhaar card and a bank account. Government functionaries on the field mentioned that registration of workers into e-Shram is a high priority task since it also uses Aadhaar as the point of access into the system.

Aadhaar Ka Aadhaar Kya Hai Bhai?

So what is the basis of Aadhaar? The power of Aadhaar in India can be truly understood when it facilitates an individual’s supply of food grains or medicines. The systematic and deep penetration of Aadhaar across the country is exemplary. A simple test is to just ask yourself—how many people do I know around me who don’t have an Aadhaar card?

Take the example of a recently piloted migrant tracking system in Maharashtra’s Nandurbar. The pilot system aims to provide Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS) services. The ICDS offers services such as supplementary nutrition, pre-school non-formal education, nutrition and health education, immunisation, health check-up and referral services. These services are of great value to the children of migrant workers who usually suffer from acute malnutrition due to constant distress migration.

Bringing migrant workers under such a scheme may be challenging. But the quickest way to bring migrant workers under the ICDS is through their Aadhaar. If Aadhaar isn’t available, the local Anganwadi workers track the migrant workers with the help of ration cards, voter IDs and personal phone numbers. If all these options fail, the muqaddam’s (contractor) phone number is the only option. This builds a case for Aadhaar as a powerful tool integrating citizens into service delivery systems.

Aadhaar makes everything easier for us and we can get them (migrant workers) the help they need faster.

—Data Entry Operator, Nandurbar

While Aadhaar enjoys a massive base of users, it does come with its share of challenges. There have been documented cases of exclusion faced by citizens because of Aadhaar. ‘Lives of Data’, a book by Sandeep Mertia, documents stories of such citizens. One such story is of Dashya Bediya, an Adivasi farmworker whose fingerprints are repeatedly rejected by the system because his hands have become rough due to the nature of his work. In an attempt to get a positive response from the biometric machine, Dashya goes on to apply layers of Vaseline on his fingers. All this to prove his own biometric data to a machine. Such appalling instances are common and Aadhaar must account for real challenges.

While biometric data is of concern, the questions around Aadhaar and its privacy issues are equally important. Privacy concerns need to be addressed in order to move towards data protection. Should Aadhaar be scrapped then? What if maintenance is better than an overhaul? Experience shows that instead of scrapping Aadhaar as a system, its redundancies could be worked upon.

“Will you please tell me about yourself?”

“Tell us why you need our information?” Asked a migrant worker in rural Maharashtra to the field officers while discussing personal data required for the provisioning of welfare schemes and services.

We need help but please tell us what these questions are for.

—Migrant Worker, Rural Maharashtra

Migrant workers shift across geographies often with their families. This is a challenging situation to be in since the destination of work is unknown and people around belong to diverse groups, not necessarily similar to those of the migrants’ nativity. The only person they seem to trust is the muqaddam who belongs to their community and travels along with them. The muqaddam holds power when it comes to the provisioning of services to migrant workers. The fruition of systems such as e-Shram is heavily dependent on the muqaddam. The question that arises then is how governments deal with the provisioning of services factoring muqaddams?

Gathering data with help of Anganwadi Sevikas is an ideal way of gathering data pertaining to welfare schemes. Among the migrant workers’ community, the Anganwadi Sevikas are trusted and usually perceived as someone who is here to help.

Collecting data is a challenge because it is tough to search and weed out where the migrants are…and then gain enough trust from them to go talk and get the data we need.”

—Field Functionaries, Chandrapur

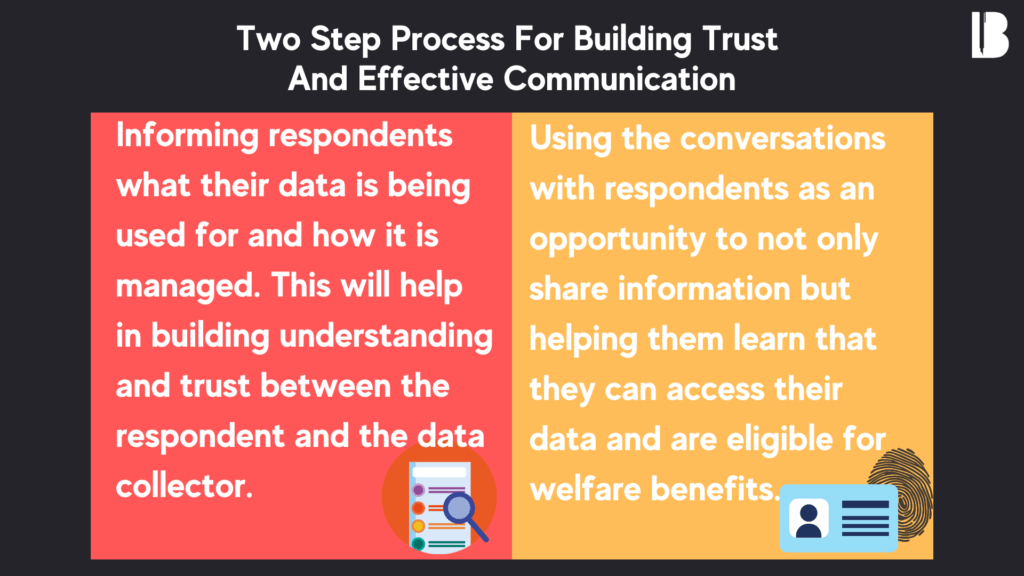

Only trust isn’t enough, the questions around data linger in the minds of migrant workers who toil day and night to make ends meet. “Why should we give you our data” is a common yet challenging question that field functionaries collecting data are asked. Many potential beneficiaries respond with a straightforward “no” during field surveys. The bottleneck identified is that the migrant workers are not told why their data is required and how it will be used. On the contrary, when the benefits are shared “there’s an uptake in the schemes we are collecting information for,” says an official in Chandrapur.

It is worth noting that every minute spent by the migrant workers answering questions, is a minute they could be engaged in work to earn wages. This is a huge trade-off, especially given that there is no visible or immediate benefit migrant workers receive for answering questions and providing personal information to the government.

Making Migrant Workers A Part Of The System

Two learnings emerge to make provisioning of services effective for migrant workers—Data collection through informed consent. The field conversations prove that these learnings are actionable. This can be achieved through a two-step effective process wherein a trust gaining exercise and an Information Education and Communication (IEC) tool is employed costing nothing.

Including these steps as part of the Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) will prove to be beneficial to migrant workers, as experience suggests. In some districts, select field functionaries have tested these steps and have indicated incorporating consistency.

Migrant workers need to be assisted further with a visit to Common Service Centres (CSC). CSCs are dedicated government access points to initiate essential social welfare schemes, public utility services and more. A CSC can be located using a CSC locator or visiting the nearest government office. It is vital that this option is made available to all, checking where the data is and which schemes can be availed with their data will create a sense of ownership. The connection between citizens and their individual data that can be accessed, edited and reviewed frequently is a good step forward. Holding these conversations on access to personal data will ensure that migrant workers are a part of the system.

The Dreams Data Promises To Migrant Workers

Transforming migrant workers’ data that transcends beyond demographic data points to protective data could be a step forward in addressing distressed migration. Data that is used to protect and serve the migrant workers will create possibilities of aspirational migration instead.

If the e-Shram portal can estimate the needs of migrant workers based on seasonal, geographical, and emergency factors such as COVID-19 to create buffer stocks of services across the country, it could then be said that we truly have created a safety net across the nation. And this would be a monumental achievement. However, e-Shram still has certain teething issues—at present, it is only available in English and Hindi and the screen reader access option meant for visually impaired users doesn’t lead to an integrated screen reader. These design changes, if implemented, could offer larger benefits leading to wider usage of e-Shram.

Other issues to be addressed are about all the data that is collected, logistics and hunger, and digital infrastructure. A senior bureaucrat working on the field says, “It is much easier to transfer data from one location to another, but food grains don’t work that way. Data flows, food does not.” The underlying logistical problem of leveraging surplus food grains needs to be examined. India is not a grain poor country. Every year we lose colossal amounts of food in storage facilities, making this one of the factors for India ranking 101 out of 116 countries in the Global Hunger Index. The World Bank reports that only 41.1% of the grain actually reaches Indian houses from stockpiles. Digital infrastructure does not always mean there is a robust physical infrastructure to support all the dreams it shows us. This loss is blamed on corrupt and inefficient logistics. We suffer from a paradox of plenty that data hasn’t solved yet. What really will the data achieve then?

Instead of developing a policy that is data-informed, we could consider a policy that is protecting migrant workers who share their data to access food, healthcare, education and other welfare measures. A data-protected policy will consider migrant workers as a unit to protect and serve. India has the experience to leverage this opportunity which can be seen in the implementation of e-Shram. The need of the hour is to create a policy that protects both data and citizens while effectively provisioning services.

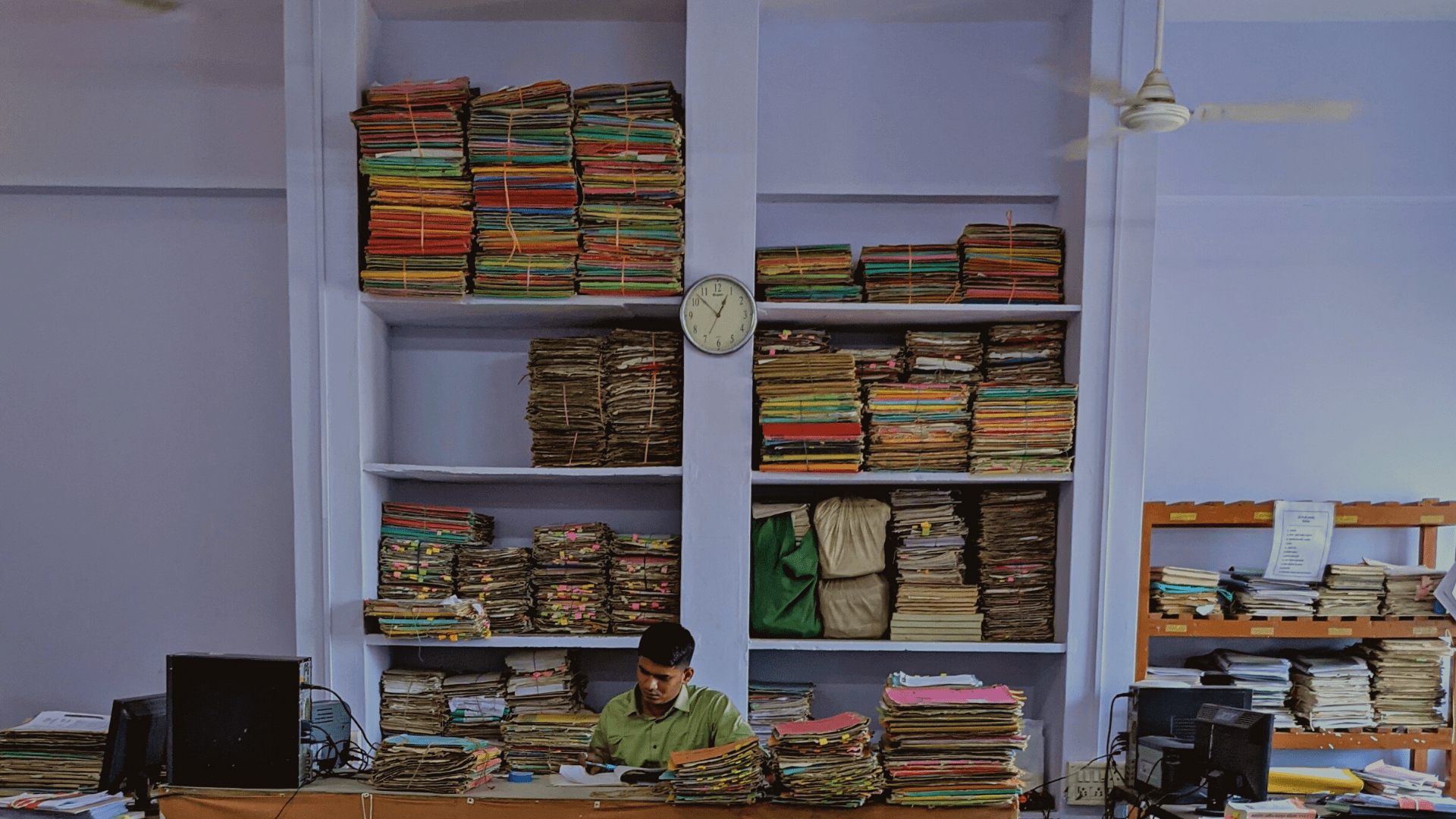

Featured image of records stored in physical files in a government offices, all of which need to be digitised to implement schemes for the informal sector by Sujay Pan.