There has been a phenomenal growth in the number of metro rail projects across Indian cities in the last decade, despite hard evidence that contests the metro rail’s financial viability, comparative environmental benefits, and overall success at improving access to public transport. Existing metro systems in Indian cities have performed miserably in improving urban accessibility, which is reflected in the fact that the current ridership of the country’s 13 operational metros remains 50 to 1,500 per cent less than official projections.

Yet, the discreet charm of the metro remains vital in the political rhetoric and policy discourse—especially given the announcement and construction of new metro projects in 21 tier-2 cities across the country.

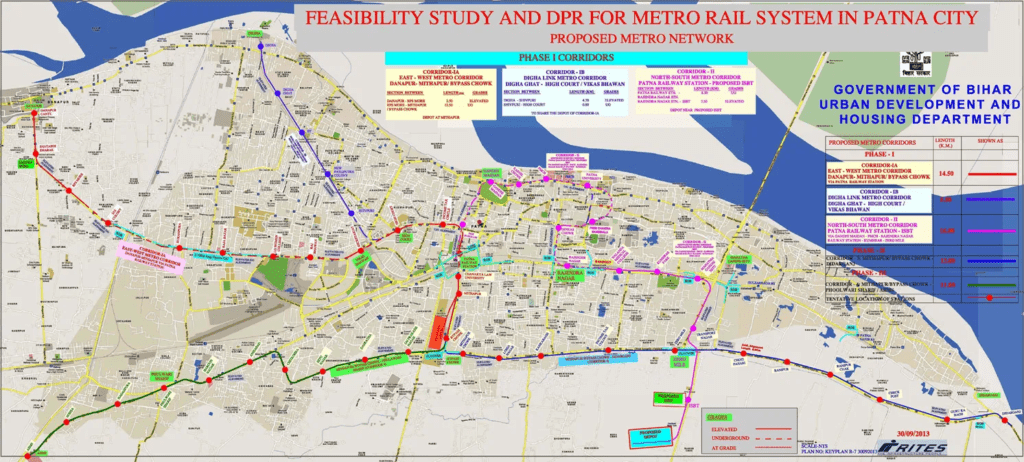

The metro rail project currently under construction in Patna is one such example. First approved in 2011 by the erstwhile Planning Commission of India, the detailed project report (DPR) prepared by the Rail India Technical and Economic Service (RITES) received clearance from the Bihar state government in 2016. Yet, the exclusionary model of the Delhi Metro Rail Corporation—one of India’s pioneering metro rails—is being replicated in the planning of metro projects in tier two cities like Patna. This one-size-fits-all approach to urban transport infrastructure does not take the existing ground realities into account, which leads to inefficient, and often detrimental, mobility outcomes in smaller cities.

The Metro Dream

Various scholars have argued that metro projects in India are the dream projects of many politicians and an essential constituent of the global branding of cities as “icons of progress and efficiency”.

Rashmi Sadana, Professor at George Mason University, has argued that the appeal of metro projects stems from the distinctly middle-class aspiration of a “global” standard of infrastructure that they seem to offer. In the process, they also restructure property values across the city, as is evident from the significant 15 to 20 per cent increase in land prices along the metro corridors in Delhi. This land capture further comes at the cost of reduced investment in other transport options such as buses, bicycles, and cycle rickshaws on which most people depend for their everyday travel. Similar patterns seem likely to unfold in the case of Patna.

Construction for the Patna Metro system began last year, and the first phase is expected to be operational by 2025. Three more phases of the project are already planned with an estimated total budget of ₹13,600 crores for a 75-kilometre long network. The DPR pegs the average daily ridership to reach a high of 2.1 lakhs by 2026. The project will be owned and operated by the state-run Patna Metro Rail Corporation, with the Delhi Metro Rail Corporation involved in planning and operations. Apart from equity contributions from the Centre and state government, a sovereign-backed loan from the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) is financing 60% of the project’s capital requirements.

However, the metro rail is not the only urban mobility infrastructure that has received policy attention in the city. Alongside this project, many large-scale road construction and up-gradation projects have been sanctioned by the state government, some of which are indicated in the Patna Master Plan 2031 prepared by the Urban Development and Housing Department in 2016.

Among these projects are the Ganga Pathway project connecting Digha to Didarganj at an estimated cost of ₹3,390 crores and the New Ganga Bridge Project, connecting Kacchi Dargah in Patna to Bidupur. The AIIMS-Digha elevated road is yet another large-scale infrastructure project inaugurated in 2020, to be constructed with international funding. The Outer Ring Road project, a proposed 140 kilometre, 6-lane expressway encircling Patna, is also on the cards, with an estimated cost of ₹4,800 crores. Apart from these construction projects, existing roads like Station Road, Ashok Rajpath, and Bailey Road are proposed to undergo widening operations too.

Yet, while many of these projects have been sanctioned to ‘decongest’ Patna’s roads, the Master Plan and budgetary allocations pay little attention to actually improving bus-based public transport and shared and non-motorised transport. “The government has virtually stopped investing in public transport and safe infrastructure for pedestrians and bicyclists in Bihar,” says Mahendra Yadav, a national convenor of the National Alliance of People’s Movements. In a 2017 study among 400 bus users in Patna, it emerged that a significant number of passengers were dissatisfied with the frequency and timely operation of buses. There were complaints about lack of availability of information at bus stops, steep fares and longer routes that discourage large scale ridership.

“The mindset of the government and the bureaucrats is such that they want to sell the metro as a gift while ignoring the pending demands for improving the bus system, providing separate lanes for bicyclists and ensuring equal road rights for all people, not just car users.” Yadav has also formed the Paidal Cycle Yatri Manch, a democratic forum of pedestrians and bicyclists in Patna. Recently, the forum organised a public meeting to discuss the need for a dedicated policy for securing pedestrians rights.

How Useful is the Metro Rail?

While the upcoming road-based projects can improve feeder connectivity to the upcoming metro network, they might also offer stiff competition, given the rise of private transport in the city.

The Master Plan document acknowledges the steep growth in private vehicle ownership over the last couple of decades. The registration of new cars in Patna grew by 90 per cent between 1996 and 2001—a trend partially attributed to the non-availability of accessible and affordable public transport and low-interest loans for purchasing private vehicles. The Master Plan reveals that most of the trips in Patna are shorter than 5 kilometres and that walking is the predominant mode of transport for the city’s residents. On top of this, the 2011 Census records that 54 percent of work trips in Patna cover distances of up to 5 kilometres. Census data also tells us that while less than 5 percent of work trips involve cars, more than 20 percent of the city’s commuters regularly use shared transport (including paratransit, buses, and trains). That this is the case reveals the glaring mismatch in terms of directing the investments to meet the actual travel needs of Patna’s people.

These plans for increasing road space for automobiles makes choosing private vehicles attractive and convenient for people in spite of the short distances they may actually need to travel. This is especially likely given the COVID-19 pandemic, and the frequent lockdown restrictions and risks of infection associated with shared public transport.

This situation could prove to be costly to both Patna metro and the commuter. As Sanjay Anand, coordinator of the Paidal Yatri Manch Bihar and an expert associated with the Sustainable Urban Mobility Network (SUMNet) says, “the metro is neither convenient nor cost-effective in cities like Patna due to the associated hassles and lack of feeder services from metro stations to the interiors [which can be accessed largely by private vehicles]. It will only be accessible to the affluent classes, and can be used for occasional special trips for ordinary people.”

These problems have emerged in the DMRC model as well: in 2019, the average trip length for a Delhi commuter was 11 kilometres, wherein “the average bus user in Delhi spends around ₹11 per trip while the Metro user spends around ₹29 per trip.” All of these factors could suppress ridership and compromise the Patna metro’s financial viability too.

An alternative way forward

As of now, the metro project appears to be more of a real estate project with some symbolic cultural importance rather than a substantial value addition to sustainable urban mobility in the city. It seems unlikely that it will get private vehicles off the road or provide affordable and accessible means of public transport to all of Patna’s residents.

These biases in public infrastructure can be countered through alternative imagination and planning. Patna’s Master Plan 2031, for example, advocates for pedestrian-oriented road design that encourages residents and workers to reduce their dependence on personal vehicles and use public transport more often. This objective also finds reflection in the Patna Smart City Project, which lays down improvement in walkability, creating bus stops, and intermediate public transport stands as some of its objectives. While these initiatives look promising on paper, it is necessary to provide more clarity on the modalities of their implementation. Reports from the ground show that no concrete projects have been initiated so far to make Patna pedestrian-friendly. “None of the guidelines for pedestrian facilities laid down by the Indian Roads Congress have been implemented in the city. These are only promises on paper that do not take into account the experiences or needs of the common man,” says Anand. In order to build awareness around the rights of pedestrians and hold the authorities accountable, SUMNet has been leading demand-based campaigns, with a larger aim of bringing about reforms in legislation.

In this context, how do we address the most pressing question of whether the upcoming metro in Patna is an appropriate response to the traffic and mobility problems faced by its citizens? With simultaneous large-scale investment in road widening and flyovers for exclusive use by private automobiles, the government is not prioritizing sustainable urban development. If several lakh people will use the metro according to the government’s projections, why should there still be such a high expenditure on adding more roads? Why are thousands of crore rupees being channelled to exclusively car-centric projects while there is no significant investment in creating safe infrastructure for pedestrians and bicyclists? Our questions along similar lines posed to the state transport department received no response from the official email ids. It is important to note that the Patna Metro Rail Corporation does not have a website even after three years since its inception. No information regarding public relations is available in the public domain either.

Experiences from the energy-guzzling cities of the developed world tell us that historically there has been a focus on new construction in response to the lack of people-friendly transport, a provenly misguided way to improve urban mobility. Ad-hoc addition of an energy-intensive transit system like the metro without systematically cutting down investments on flyovers and road expansions in Patna is highly likely to add to the overall ecological footprint of the city. This is likely given the life cycle emissions given out during the production of various components of the metro system, and the fact that coal is the predominant source of electric power used to run it. Moreover, as the recent experiences of the COVID-19 lockdowns confirm, running expensive metro systems leaves state governments more vulnerable to economic shocks and unpaid loans.

It seems that the government’s interest is in the proliferation of construction projects instead of raising the levels of accessibility to public transport. Those who need affordable and environmentally appropriate public transport will have to wait.

This article has benefited from the support provided by the People’s Resource Centre. | Featured image: traffic in Patna, Bihar; courtesy of Satwik Shresth on Unsplash.

Hii Debapriya and Nishant. I am Shalini, a Post graduate student of City Planning at IIT Kharagpur, and I was doing some research about the impacts of Metro on the land use and urban form of Patna for my final year thesis when I came across this article of yours which has made me think of this entire study in a different perspective and questioning the feasibility of metro in Patna. So I really appreciate your work and would like to connect to both of you for some further discussions on the topic. My email id is [email protected]. Please do connect.