Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is a legal mandate under the Companies Act, 2013.

It imposes a responsibility on companies having a net worth of ₹500 crore or more, or turnover of ₹1,000 crore or more, or a net profit of ₹5 crore or more to invest at least 2% of the average net profit made during the previous three years for a social cause defined under Schedule VII of the Companies Act, 2013. The law permits corporations to do this either through a non-profit set up by such a corporation itself, or through other non-profit entities such as public trusts, charitable societies, or section 8 companies which have been operational for three years or more.

Often, not all corporations have their own CSR arms and therefore, they must identify and work with other non-profit enterprises to fulfil their CSR obligations. For example, GenPact CSR supports Akshaya Patra (which provides mid-day meals in schools) and Teach For India (which works in education). Wipro CSR, on the other hand, supports Fourth Wave Foundation (which works with people with disabilities) and Pratham (which works in education).

Now, this appears to be a simple transaction. However, CSR puts the corporate in a self-assumed position of the grantor and the receiving non-profit in the position of a grantee. The underlying relationship of a giving grantor and a receiving grantee—and the related power dynamic between the two—tips the negotiating power against the grantee and puts it in a disadvantageous position.

This power imbalance also flows into the grant agreement that seals the CSR relationship between the two parties. Admittedly grant agreements must clearly lay out expected obligations of the grantee, outcomes of the grant, and ensure that there is 100% accountability for the funds dispensed. Unfortunately, grant agreements for CSR activities go beyond this and nearly stifle grantees in the name of ‘good governance’ and ‘compliance’.

The grant agreement reflects and amplifies the unequal power dynamic inherent to CSR, which manifests in the form of unfavourable, if not draconian conditions on the grantee. Where must the line be redrawn to create a more equitable social impact environment?

Unraveling the Grantor-Grantee Relationship

A grantor perceives itself as a ‘giver’ of funds and the grantee as their ‘receiver’. The relationship is often reduced to strictly monetary terms and nothing more.

However, a grant is much more than just money. It is an opportunity to bring about social change, wherein the grantor provides the financial resources and the grantee possesses the knowledge and power to create social impact.

In this scenario, the value of the knowledge, power, and last-mile connectedness a grantee possesses to implement a program should never be positioned ‘lower’ than monetary support.

Simply put: to fulfil CSR responsibilities, it is not only the grantee who relies on the monetary support of the grantor, but also the grantor who relies on the knowledge, networks, and power of the grantee.

Therefore, the power dynamic that places the grantor on a higher pedestal than a grantee is based on a false sense of entitlement. To say the least, a grantor and grantee must be construed as equal partners—especially when it comes to grant agreements.

Grant Agreements: Hardcoding Biases Against Grantees Knowingly Or Unknowingly?

Are grant agreements drafted with due cognizance of the various sensitivities of the social sector? Or, does the grantor’s legal counsel tweak vanilla templates of commercial agreements to formulate a grant agreement?

In our experience at Pacta, CSR grant agreements often appear to be drafted in the latter format.

The grant agreement—a legally binding document—lays down the outline, purpose, and scope of the grant. The rights and obligations as defined in the grant agreement set the tone of the grantor-grantee relationship.

Typically, the grant agreement originates from the grantor and the grantee can only review and suggest changes to it. This puts the grantee at a disadvantageous position from the get-go. Misconceived and reductionist notions of the grantee—which are shaped by the ‘benefactor’ pedestal grantors are placed on—are often mirrored across the agreement.

Some examples of draconian clauses hard coded into CSR grant agreements include clauses that give no termination rights to the grantee, no intellectual property rights over data collected or reports generated, and one-sided conditions allowing the grantor to withdraw and seek refunds of the funds disbursed.

There’s also the case of rigidity in fund utilization—or permitting little or no interoperability in budget line items—which goes far beyond the already stringent legal provisions applicable to nonprofits. During the project implementation of a CSR initiative, conditions often vary, and the grantee might be required to alter deadlines or budgeted line items. However, CSR grant agreements do not provide for such flexibility and mandate that every alteration must be pre-approved by the grantor, thus further delaying the already slow-moving bulwark of the social sector. For example, in a CSR grant agreement to provide education in rural areas, a provision that limits the cash withdrawals and payments for meeting monthly expenses to a maximum of ₹10,000 restricts the scope of activity of the non-profit organisation. First, a non-profit implementing an initiative in a rural area may find it difficult to manage cash payments within the defined limits. Furthermore, the condition to take approvals from the grantor for cash withdrawals beyond ₹10,000 adds to the difficulty of implementing the initiative.

But, should grantors take such a hard stance towards the grantee? The answer is no.

Under the current legal framework, non-profit organizations are subject to strict governance and regulatory measures. For instance, the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act, 2010 (FCRA) requires non-profit organizations to be registered with the government, file annual returns, and provide quarterly intimation of the receipt of foreign contributions. Under the Income Tax Act, 1961, organizations are further required to file income tax returns, conduct statutory audits, and file Tax Deducted at Source (TDS) returns. Similarly, non-profit organizations are not exempted from compliance with labour laws, sector-specific laws (such as those relevant to education or healthcare), or data protection laws.

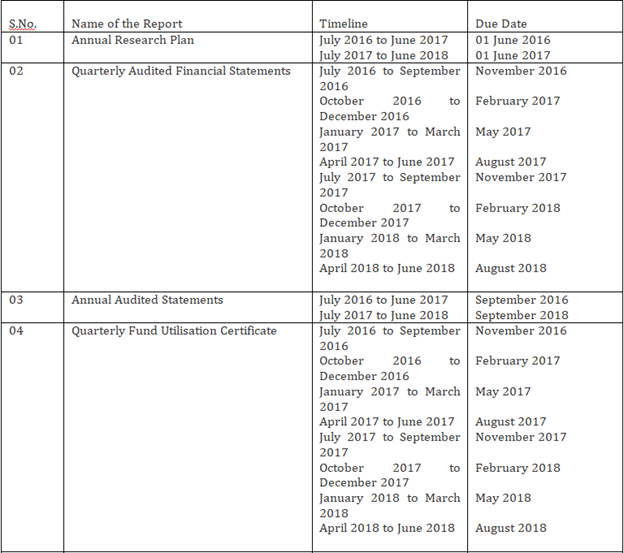

Given that non-profit organizations are already regulated by a basket of stringent laws, CSR grant agreements should take advantage of existing legal frameworks instead of creating additional onerous compliance requirements. For instance, a long list of financial statements, as indicated in the image below, can be avoided by relying upon the annual statutory audit carried out under the Income Act, 1961. The grantor may also align the audit timeline with the audit timeline mentioned under the Income Tax Act, 1961, that is, 1st April to 31st March of the financial year.

Nevertheless, the grantee usually undergoes several rounds of review and negotiations before finalizing the grant agreement, to hopefully overcome these hurdles. However, even during this process, grantees often face tone-deaf statements such as, “Why does the grantee need the power to terminate CSR grants? Why will they terminate the agreement at all? They need the money, right?”

Mind The Gap: Understanding the Grantee & Developing Grantee Capacity

A CSR grant document with complex reporting procedures, intrusive audit practices, and threatening deadlines might indicate that the grantor has little or no faith in the grantor. This must change, especially given the back-drop that just as for-profit start-ups raising investments go through a due diligence process, not-for-profit grantees also go through extensive scrutiny and paperwork prior to being selected for a grant.

It is not unreasonable then, to expect that the reporting and evaluation process for a grant is designed with due understanding of the grantee’s work and impact model. Scale is another important factor to be considered while drafting these agreements.

While we certainly don’t suggest compromising statutory compliance, a grantee’s scale and capacity for impact measurement and reporting must form an intrinsic part of a grantor’s understanding of the grantee.

Smaller nonprofits do not have the human capital and other infrastructure to meet the onerous compliance standards set out by CSR grantors. In such a scenario, it falls upon the grantor to bridge this gap and enable the grantee to develop capacity in domains of financial reporting, impact evaluation, and compliance/governance. Here are a few recommendations on how to break this cycle of ignorance, mistrust, and power imbalance embedded into CSR grant agreements.

- Reporting and Evaluation

Transparency is the key to the effective and proper utilisation of funds. While proper reporting procedures must be put in place to ensure transparency, they should be formulated after paying due consideration to the nature of the grantee. The agreement shall not be employed to impose avoidable reporting procedures that may potentially impose administrative burdens on the organization. The grantor shall aim at formulating a simple and flexible reporting clause that accommodates the needs of both parties.

- Audits and Accounts

Grantors often require the grantee to submit periodic audited statements of funds disbursed by the grantor, in addition to the financial statements that are usually prepared to meet the law of the land. Whether such needs are real and whether such reports need to be tailor made for the grantee must be asked and conclusively settled before placing them in grant agreements.

- Intellectual Property (IP) Rights

The IP clause protects the grantee’s rights over the data, data analysis, and research findings created using the grant funds during the term of the grant. When the grantor refuses to grant rights on IP created and treats it like a commercial “work-for-hire”, such a clause becomes a blocker in the grant-negotiation. Instead, the grantor can adopt good practices such as nudging the grantee to adopt open sourcing of intellectual property to the extent that is permitted by law.

- Publication Rights

Grant agreements often require grantees to publish their work and association with organizations to show the nature of work they are doing or are capable of. However, the grantors often retain the rights over the IP, restraining the grantee from publishing project related documents even after the conclusion of the project. The grantor must understand that the grantee is best positioned to publish research work. An effectively drafted clause providing attribution to the grantor, but simultaneously waiving the grantor’s liability of the content will both protect the grantor and allow reasonable liberties to the grantee.

- Termination Rights

A grantor should not be entitled to terminate the agreement unilaterally. Grantors need to acknowledge and accept the possibility of a scenario where the grantee might want to terminate the agreement. Therefore, an ideal agreement will have a termination clause that gives a mutual right of termination.

- Grant Nomenclature

William Shakespeare once famously wrote, “what’s in a name?” We say, a lot. The way parties are addressed as grantor and grantee reflects a unilateral give and take arrangement. Rather, the parties can be referred to as ‘grantor’ and ‘partner’ to allude to a partnership of sorts, or even go by their entity names to signify equanimity in the relationship.

- Grantee Feedback

Once the grant process concludes and the objective has been achieved, it is pertinent for the grantor to pursue the grantee for feedback—which is not necessarily standard practice right now. Such feedback gives voice to the concerns and challenges faced by the grantee. Grantee feedback has also allowed organisations to ensure transparency, provide non-monetary support to grantees, and build strong relationships with grantees.

In the grant-making process, the grantor-grantee relationship is often tainted with mistrust, a sense of entitlement, and a lack of understanding. CSR grant agreements must therefore be conceived as documents that aim to strengthen ties between the corporate and social sectors, and that balance out mutual expertise to achieve effective social impact. Afterall, that is the original intent of making corporate social responsibility compulsory.

Featured image on Wesley Tingey on Unsplash.