In November 2021, the National Health Authority (NHA), the nodal agency concerned with rolling out the Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission (ABDM) programme, released a consultation paper on the Health Data Retention Policy (HDRP). This policy could be a promising move that can promote access to reliable and quality health data by laying out a framework for sharing and using health information through interoperable systems. More specifically, the HDRP poses the limits to the retention of health data by healthcare facilities, with attendant recommendations on health data classification, modes for retention, and exchange of such data.

Though well intentioned, the policy abounds with ambiguities. There is little clarity on the HDRP’s scope and applicability given the amorphous definition of “health facilities” guiding the policy. Similarly, the HDRP’s recommended blanket period of retention for different classes of health data as well as treatment of data in anonymised form needs to be re-examined to account for the potentially hazardous ramifications to the privacy, security and rights of data principals [the patients concerned].

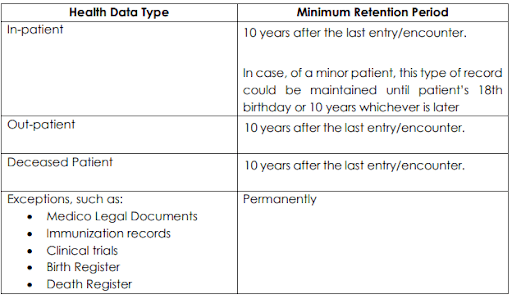

The implementation and enforcement of the HDRP are two interrelated questions that beg for greater clarification and support from the state. The HDRP adopts a taxonomy-based approach to decide the periods of retention. However, this taxonomy is futile considering that under Section 5.2 of the HDRP, in-patient, out-patient and deceased persons data are all meant to be stored for 10 years each. The other exceptional cases such as medico-legal cases, immunisation, birth and death registries are meant to be stored permanently.

What’s Under the HRDP’s Ambit?

While the Health Data Retention Policy (HDRP) consultation paper asks stakeholders if the policy should be applied horizontally across the health sector or be restricted to entities participating in the Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission (ABDM), certain concomitant concerns arise.

Firstly, the National Health Authority (NHA) is specifically mandated to implement the ABDM programme. As a result, the HDRP does not possess constitutional authority to enforce horizontal policies for the health sector. This is because the NHA fails to pass the test for legality established by the Supreme Court in its K. Puttaswamy verdict.

The Test for Legality

The K. Puttaswamy verdict is crucial inasmuch that it lays down a four-part test for infringement of the right to privacy which includes: legality, legitimate goal, proportionality and procedural guarantees. To begin with, the test for legality mandates the existence of a law to back state action on health data retention. The NHA fails this test for legality as it is an extra-constitutional body set up through executive action with a limited mandate to oversee the implementation of the Ayushman Bharat Digital Health Mission. Consequentially, the NHA has not been established by an act of law (parliamentary action) and hence, fails the test for legality under the K. Puttaswamy verdict. Therefore, the NHA cannot call for sector-wide coverage of the HDRP since a legal mandate is required to implement such actions.

Secondly, the HDRP necessarily abides by the definitions set out in the NDHM Health Data Management Policy (HDMP). The health facilities under the HDRP, as stated in Section 4(p), include “hospitals, clinics, diagnostic laboratories, health and wellness centres, imaging centres, pharmacies and others as may be specified by NHA from time to time” only. This amorphous definition, without clarity on “other” facilities to be defined by the NHA, risks excluding new and emerging digital platforms like telemedicine and app-mediated healthcare service providers that collect and process patient’s personal and health data all the same.

As a result, the policy potentially leaves widely-used ovulation and fertility tracking apps, like Flo, known for selling user data, out of its ambit. In a similar vein, the uptake for telemedicine services in India has only risen during the pandemic, with the telemedicine market peaking at a whopping $163 million in March 2021, but the policy fails to cover this segment.

Also Read: Femtech Says It’s Empowering Women, but Is It Commodifying Them Too?

The HDRP fails to keep up with the transformative digital health ecosystem that it seeks to govern. Such a glaring omission, in the context of previous healthcare data breaches in India, has resulted in the leak of 68 lakh records.

Does Anonymisation of Data Make the HDRP Any Better?

The Health Data Retention Policy (HDRP) suggests a blanket retention period of 10 years for different types of datasets corresponding to in-patient, out-patient and deceased persons’ health information. However, storing sensitive health information for long periods of time comes with considerable risks, particularly due to perilous data breaches threatening India’s healthcare system. Without adequate safeguards against these threats, the HDRP ignores the security and privacy risks.

To make matters worse, the HDRP hosts a provision to share anonymised health data with health information users. While patient consent is necessary for processing of personal health information, it is not necessary under the HDRP to obtain the same for sharing anonymised health data. To this end, re-identification of anonymised health information is a credible possibility, given that there is no fool proof method of anonymisation globally.

The absence of an overarching framework to govern the use of personal and non-personal data in the Indian context complicates such recommendations—there is no operative data protection legislation to redress harms arising from re-identification of data and consequent loss of individual as well as group privacy. Specifically, the absence of stipulations on how non-personal data is used and for what purposes could imply that such data might not be used in the best interests of the patient community, as patients cease to have control over their health data once it has been anonymised.

Also Read: Data Data Everywhere, Whose is it to Give?

Another significant, but oft-ignored perspective on sharing of anonymised data is the value it possesses, how it is distributed and who benefits from it. Decisional autonomy [the ability to exercise meaningful control over use and sharing of one’s own data] is grossly neglected within the current consent architecture of the HDRP. And so, it is the health facilities and public agencies that emerge as final arbiters of health data exchange, not individual patients and patient groups that helped produce this information in the first place.

Here’s How the HDRP’s Implementation Could Look Like

Who would be the appropriate regulatory authority to oversee the implementation of the Health Data Retention Policy (HDRP)? This question, an important one, begs attention. The National Health Authority (NHA) is not constitutionally empowered to implement the policy as it fails the test for legality established by the K. Puttaswamy verdict, as established earlier.

In the absence of a specialised sectoral authority for health data, the proposed Data Protection Authority (DPA) could be designated as the apex authority to enforce the HDRP. The DPA, as contemplated by the Data Protection Bill, 2021 can not only ensure protection of the interest of data principals, the patients, but is also empowered to adjudicate on issues arising from data misuse.

The enforcement of the HDRP requires building institutional capacity of health facilities to transition to a digital ecosystem for health record maintenance. This is a debilitating bottleneck for small clinics and public health facilities, particularly those in rural India, which suffer from poor internet connectivity, absence of trained personnel and inability to bear the steep costs involved in digitisation of health records. Factoring the ground realities, the HDRP remains glaringly silent on furnishing support necessary for digital transformation of India’s health systems.

Reimagining the HDRP for a Better Digital Health Ecosystem

The Health Data Retention Policy (HDRP) must be re-imagined from multiple perspectives. To begin with, informed consent must be the bedrock of any framework seeking to store, process and share data of patients. It is crucial for the HDRP to imbibe this principle while seeking to regulate health data. Data principals should be included in every step of the data value chain and their free, fair and informed consent should be sought before data, in any form, is further processed and shared with requestors.

To achieve this, an ‘opt-out’ option for data principals, which could restore their agency and control over data-related decision-making, needs to be included. This will ensure that patients have the choice to opt out of anonymisation and sharing of their anonymised information. Global precedent exists. The United Kingdom’s National Health Service (NHS) introduced a national opt-out service that helps record the preferences of individual patients on data sharing and prevents the NHS from using the data of unwilling patients for any purpose.

The HDRP’s provisions on time periods for health data retention could borrow from The Indian Medical Council (Professional Conduct, Etiquette and Ethics) Regulations, 2002, which suggest retaining patient data, both in-patient and out-patient, for a period of 3 years, from the date of hospital visit or commencement of treatment. Any move to extend the period of retainment must be authorised by explicit patient consent that should be obtained each year. Embedding this additional safeguard will ensure decisional autonomy of patients.

If the above is ignored, this ‘one-size-fits-all’ system to health data retention—10 years for in-patient, out-patient and deceased persons’ data—is an undesirable move for many reasons. For instance, the patient’s out-patient information about prescriptions of antibiotics is not as important as, say, in-patient data on the nature of cancer treatment administered to another patient. However, for the HDRP, all data— in-patient and out-patient—have to be stored for 10 years. This not only maximises the privacy risks due to data breaches and re-identification of anonymised data, but also creates undue regulatory and compliance burden on health facilities, in particular to the smaller clinics and dispensaries that may not have the digital capacity to maintain records for so long.

The passage of the proposed Data Protection Bill, 2021 is indispensable to upholding consent and other data rights of individuals. The HDRP must not only comply with the provisions of the aforementioned Bill but also be rolled out nationally only after India implements a comprehensive data protection regime for its citizens.

Featured image is of a doctor examining a patient during and making note of her health at a free health by Bharat Nirman Public Information campaign in Tamenglong district of Manipur in 2011; Image courtesy: Ministry of Information & Broadcasting (GODL-India) via Wikimedia Commons.