As Finance Minister, Nirmala Sitharaman finds herself at a unique moment in India’s history. She has just announced a Union Budget bearing a number of policy measures to revive the country’s economy from a devastating pandemic that has taken over 1.5 lakh lives and displaced millions of vulnerable livelihoods. The FM’s“get well” speech in the Lok Sabha conveyed that the Government aimed to tackle the crises induced by the COVID-19 pandemic by focusing on disinvestment and self-sufficiency (read: “Atmanirbharta”), but a standout was the increased outlay towards health and well-being.

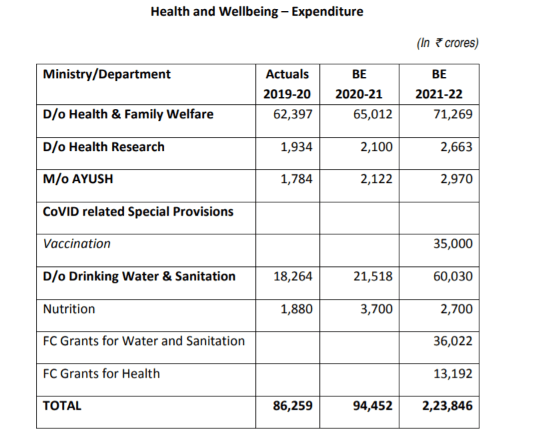

The government has estimated an expenditure of ₹2,23,846 crore on health and well being, which has been lauded because it is a 137% increase from the budgeted amount last year. While prima facie this seems to be a huge and necessary improvement, it is important to note that large chunks of this outlay includes spending on water supply and sanitation. The Jal Jeevan Mission, for example, has been included, although it is a project that aims to increase tapped water supply to urban households. Sizeable allocations have also been made towards nutrition and preventative measures, besides a ₹35,000 crore allocation for COVID-19 vaccination.

Playing a Forced Hand

At the outset, an increase in allocation toward health schemes would have been unlikely under non-pandemic circumstances. As of 2018, India spent only $275 per capita on health (in purchasing power parity terms), in comparison to China’s $935, Russia’s $1488, and Brazil’s $1530. Typically, a country’s focus on health is measured by the share of public health expenditures of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which stood at 3.54% for India as of 2018.

In order to understand how healthcare has been approached vis-a-vis budgetary allocations, it is useful to consider how similar changes in public spending were induced by extraordinary junctures in post-independence India. For example, between 1974 and 1984, public spending (as a share of GDP) nearly doubled, from 12.5% to 23.5%. The same shift can be seen in fiscal expenditures during the Global Financial Crisis (2008-2011).

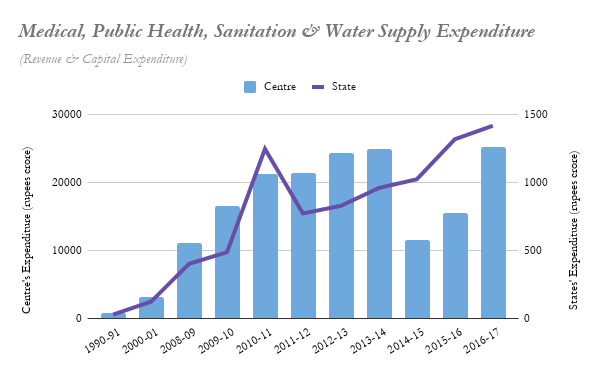

Albeit at a slow pace, since the 1990s, the Centre and states’ expenditures on public health have been increasing. Spending on health was cut by nearly 53% in 2014-15, and the following year also saw it take a backseat in terms of priorities. Two shocks are noteworthy in this time frame: 2014 was the year of the ‘Taper Tantrum’ crisis, following The Federal Reserve’s decision to potentially reduce quantitative easing in the United States of America in 2013. 2014 also marked a change in political regimes at the Centre.

The 2021-22 allocations are of consequence because health and social-spending in India have been historically low. As the 2020 Economic Survey notes, out-of-pocket expenditures on health are among the highest, accounting for nearly 17% of total household expenditure in India. These present compelling reasons for India to implement longer-term changes in healthcare spending to protect households, especially poorer ones who face the heaviest burden of healthcare expenditures.

Centre-State Responsibilities for Revival

Initial data from the Union budget suggests that the level of spending on health measures related to COVID-19 is unprecedented. This is not particularly surprising, because India has never faced a pandemic as widespread and damaging as COVID-19. There have been localized outbreaks and epidemics such as H1N1 (swine flu), H5N1 (avian flu, that recently resurfaced), and the 1994 plague in Gujarat. Such outbreaks have typically been dealt with at the state level itself, with some help from central health agencies.

The 1994 bubonic and pneumonic plague was largely confined to Surat city, although the Union government worked to mitigate the spread of misinformation and panic in other parts of the country. It became the Surat municipal corporation’s responsibility to fumigate and sanitize areas where the plague had spread, with little aid from the Union government at the time. Centre-state coordination during the H1N1 epidemic since 2009 have remained restricted to the Union monitoring the spread of disease; states would work to contain the virus with the best of their available resources at the district level. In Pune, for example, the Union health ministry set out guidelines and monitored the H1N1 virus, whereas state authorities in Maharashtra worked towards creating capacity for handling more cases and screen potentially infected persons.

As for the coronavirus, it is important to keep in mind that health expenditures are not solely incurred by the Union; in fact, health continues to remain a State subject, with the pandemic prompting calls to shift it to the Concurrent list. The key argument is that since the Union and states share responsibilities and expenditures when resolving a health crisis, which requires a cooperative federalist approach. As with earlier outbreaks, the COVID-19 virus has spread heterogeneously across states, thereby prompting different intensities of response from state governments. Many states have had to dip into contingency funds to meet expenditures (medical equipment, gloves, etc.

Recent reports suggest that the Centre plans to use funds from the PM-CARES Fund to meet vaccination-related expenditures. The FM’s budget speech mentioned that grants will be made to local bodies to meet expenditures related to vaccines, among others. Measures such as the 500+ crore boost to the Ministry of Health Research is a step in the right direction, as the country continues to monitor the efficacy of the vaccines in the coming months.

Between 1990 and 2017, the combined expenditure on health by the Centre and states has been stable, at 4-5% of the GDP. Through these years, although budgetary allocations have grown, there are compelling indicators that show that this growth is insufficient. In 2018, the out of pocket health expenditure of Indians was nearly 62.67%. Given that only 15% of the population has health insurance, it is likely that the pandemic has increased the already high burden of out-of-pocket health expenditures over the past year.

Can such prioritisation be sustained?

In specific, the Ministry of Health has been allocated ₹71,269 crore, which is nearly 9% greater than last year’s budgetary estimate, but still less than the ₹78,886 crore which the Ministry ended up actually spending.

Data from the most recent National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) indicates that child malnutrition (especially under the age of 5) has worsened. This is something that needs to be focused on beyond budgetary allocations. Mission Poshan 2.0, which is a consolidation of existing child nutrition schemes — the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS), Anganwadi Services, Poshan Abhiyan, Scheme for Adolescent Girls, and the National Creche Scheme — is said to also be targeting 112 aspirational districts in the country. The fact that it aims to improve nutrition amongst three sections of the population (children, pregnant women and lactating mothers) is an indicator that beyond outlay, the focus needs to prioritise program design.

Lastly, it is worth considering whether this jump in health expenditures is likely to be sustained, and what effects that might have. The country’s fiscal deficit has ballooned to 9.5% of the GDP, which is a clear consequence of the unplanned expenditures that COVID-19 has prompted from the Union budget. This is of concern because meeting the target (set at 6.5% of fiscal deficit) for the next budget may be a challenge given the uncertainties surrounding COVID-19 (including new variants, and struggles in other countries for vaccine distribution). Part of the funds will be raised from ongoing disinvestment and privatization of public sector units. Having said that, a pre-budget survey from Bloomberg indicates that India’s condition is no outlier in the world.

The BJP-led NDA may well look back at the 2021-22 Union Budget as one of their biggest priority checks, after what has been a tumultuous year. On paper, especially in relation to our historical negligence, they seem to have come good on vis-a-vis recognising the importance of a healthy population. Yet, most of the allocated expenditures have focused on preventive health measures, which may not create the kind of lasting capacity needed to manage future health emergencies. If and when COVID-19 related expenditures can be scaled down (following vaccine distribution to far-reaching parts), the next point of focus should be on nutrition and mental health — which received no increase in outlay, what with the FM including “well-being” and “anxiety” probably for first and last time in a budget speech.