This article is the first of #FinancingDevelopment, a series analysing the finances behind India’s development journey, in collaboration with the Centre for Financial Accountability.

In India, private firms running services are not democratically responsible to the public. This remains to be an issue with large-scale infrastructure projects in which private companies are involved. It has become normal now for private companies and the government to negotiate contracts for public works without seeking inputs from citizens. There is hardly any public accountability, transparency or scrutiny for such infrastructure projects.

What makes these issues even more complicated is ‘commercial secrecy’ wherein companies are not subject to demands under the Right to Information Act (RTI). Most commercial information such as revenue projections, profits, or interest rates are not publicly available. When private companies fail to deliver, the public has no power to intervene, and the government, both local and national, does not always have resources or expertise to bring these companies to account.

According to economist Rathin Roy, Economist and Managing Director,ODI; Senior Visiting fellow at the Centre for Policy ResearchI; Former Director and CEO, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP), the government has been facing a ‘hidden’ budget problem. A succession of disasters, including demonetization, the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) and a 1.45 trillion rupee tax cut for companies, completely destroyed the economy. In order to make up for the corporate tax cuts, the government was compelled to drastically increase the cost of inelastic goods like petroleum products. Lower- and middle-class consumers indirectly bear the expense of the increase in direct taxes; as a result, their spending falls and further slows GDP growth, suggests Roy.

So why does this situation arise? The lack of due diligence and safeguards for private entities’ operations and policies creates a highly privatised environment, further widening the scope for unaccountability, which affects employment. It is a usual practice for private entities to hire their own trained personnel to manage the assets they have paid for. Often, it is the foreign capital that is driving the creation of this infrastructure, which means that domestic and small retailers are not given importance on such development finance projects. Further, a situation might arise where a large number of infrastructure projects are owned exclusively by private and foreign investors—ushering private monopolies. The lack of effective due diligence and adequate safeguards could result in the concentration of India’s public assets in the hands of a few. The end result of this could be the exploitation of common people and small investors, environmental degradation and economic uncertainty.

While it is easy to point fingers at private entities, it is also critical to assess why the government is unable to address the repercussions caused by such private infrastructure investments in India. How did we get here?

The Politics of Investment and Development

To make investing in India’s infrastructure exciting for private investors, the government has been rolling out several policies, regulations and tenders. This is seen in fast track investment approvals, incentive programmes, subsidies, land banks, and a more liberalised criteria for environmental clearances. For private investors, speedier the processes, higher the returns—a fact that the government also understands well. The government also finances infrastructure projects through loans, debt or equity investments, and monetary authorities such as the Reserve Bank of India does this through the lowering of bank rate. Availability of easy and cheap credit is key to driving infrastructural growth and has an impact on construction industries, transport and co-operative sectors.

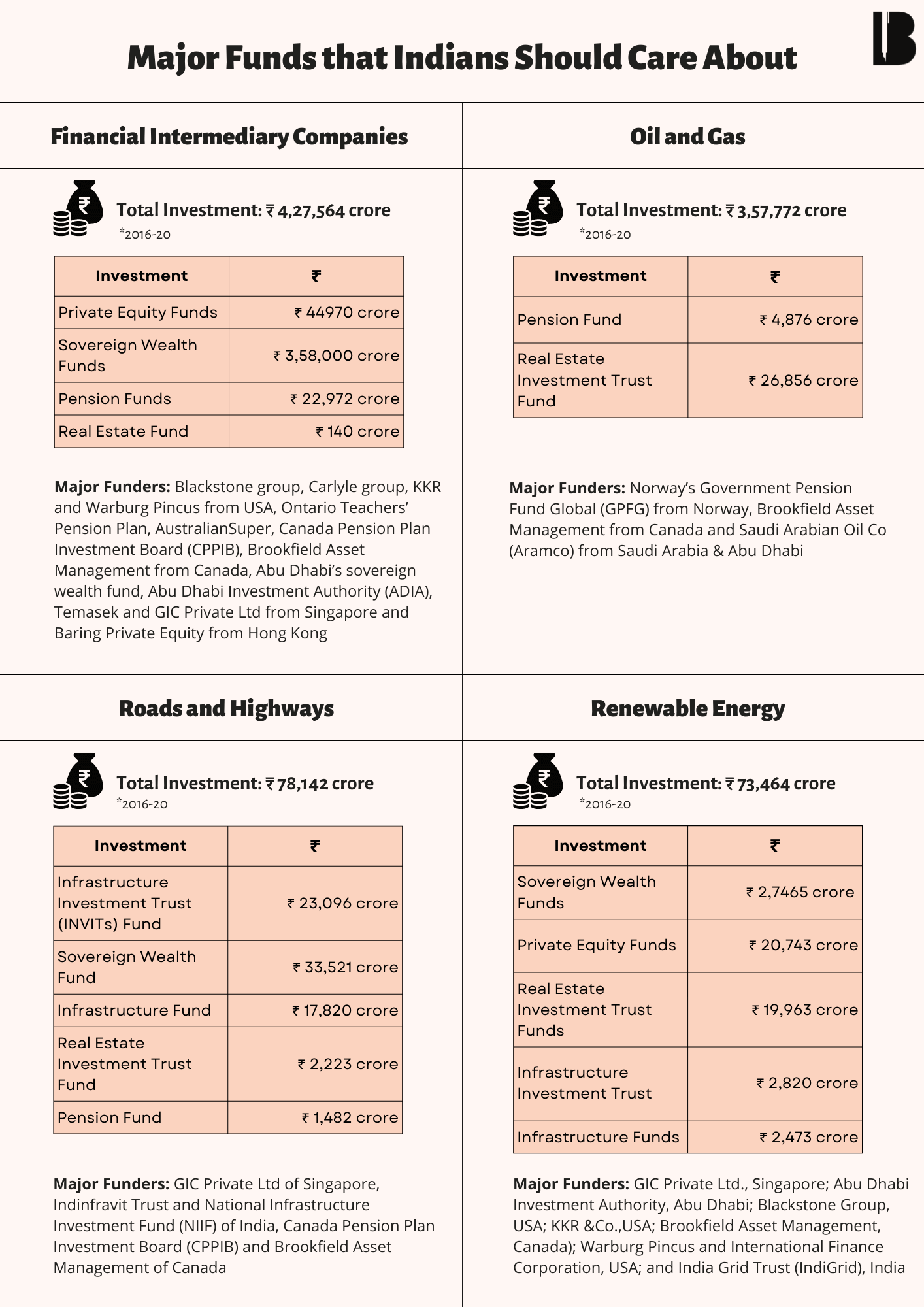

Delaying the granting of environment and forest clearances raises concerns over timely completion of significant projects. To address this challenge, the government has established a single body known as the National Investment Approval Board (NIAB) to approve such infrastructure projects. This makes NIAB in charge of accelerating clearances for mega project proposals above a certain financial threshold. As investments and development in India continues to be driven by political and commercial interests, as citizens, the three sectors to care about and watch closely are roads and highways, oil and gas, and financial institutions.

Over the past few decades, it has been observed that the government is good at devising plans on paper, but has not been able to implement and maintain them in the desired manner. Due to such inconsistencies in the government’s plans, the private sector is usually brought in to improve the efficiency, productivity and operations of projects. What is expected from the private sector is producing additional resources to revive the economy and leverage monetised assets, which will contribute in building new infrastructure. Finding enough resources to construct physical assets is a challenging feat due to the claimed infrastructure deficit. This remains a claim since there is a gap in understanding whether these projects are absolutely required as there are other factors too for infrastructure deficit—infrastructure is built for whom, what are the services being provided and to whom does it benefit. One way the government could raise the required capital for these initiatives is by enlisting private investors to make investments in goods and services, which will help in mobilising private capital—both domestic and foreign. Infrastructure projects ultimately need to improve the lives of the citizens.

The Changing Course of Public Service Delivery

Private entities start their business operations in India to generate profits, while the government’s strategy is to provide the public with quality services. The ability of the Indian private sector to invest at large scale is also doubtful and according to the Centre for Financial Accountability’s research, investments made by foreign firms are considered crucial. How does this change the language of public service delivery, what are the setbacks and advantages of such a strategy, and what happens when the objectives are not met?

A sharp rise in private investments would probably lead to monopolisation and inflation. Monopolies and lack of accountability in the provision of essential services could influence the stability of the macro economic and social environment. As both public and private funds begin to own shares in public assets, private entities could demand that their management should not be controlled by the public sector, which would create conflicting interests. In the case of inability to deliver, private entities could refer to the economic and political stability of long term contracts and assurance of independent regulations.

A job market with inconsistent employment patterns may arise from placing ownership in the hands of private players. This means that the future may see a labour market straddled with erratic job losses, hires, and wage reductions. Private businesses would prefer to exclusively work with labour that meet their technical standards and are highly competent. This would mean that the less skilled labour might be at a disadvantage and face uncertainty, leaving them to the whims of the market.

Another, more crucial question is the successful operation and implementation of the projects in which private companies would invest. Who will pay the price for such massive failures if these projects fail to produce the intended results? In order to make up for these losses, the ordinary population will probably experience higher taxes and inflation.

Since the taxpayers are already paying for the public resources, there is no reason for them to also pay a private entity to use them. To put it simply, the construction of toll roads is done using budgetary allocations from tax collections, however, once the roads are constructed the citizens have to pay toll charges over and over to use the roads. Over the past several years, the taxpayer’s money has been used to construct public assets in industries including mining, communications, power, ports, trains, and transportation. These resources, which make up the nation’s essential infrastructure, are now all of a sudden being made available to private investors and there is often little clarity on the compensation offered to the taxpayer.

Towards a $5 Trillion Economy by 2025—What’s at Stake?

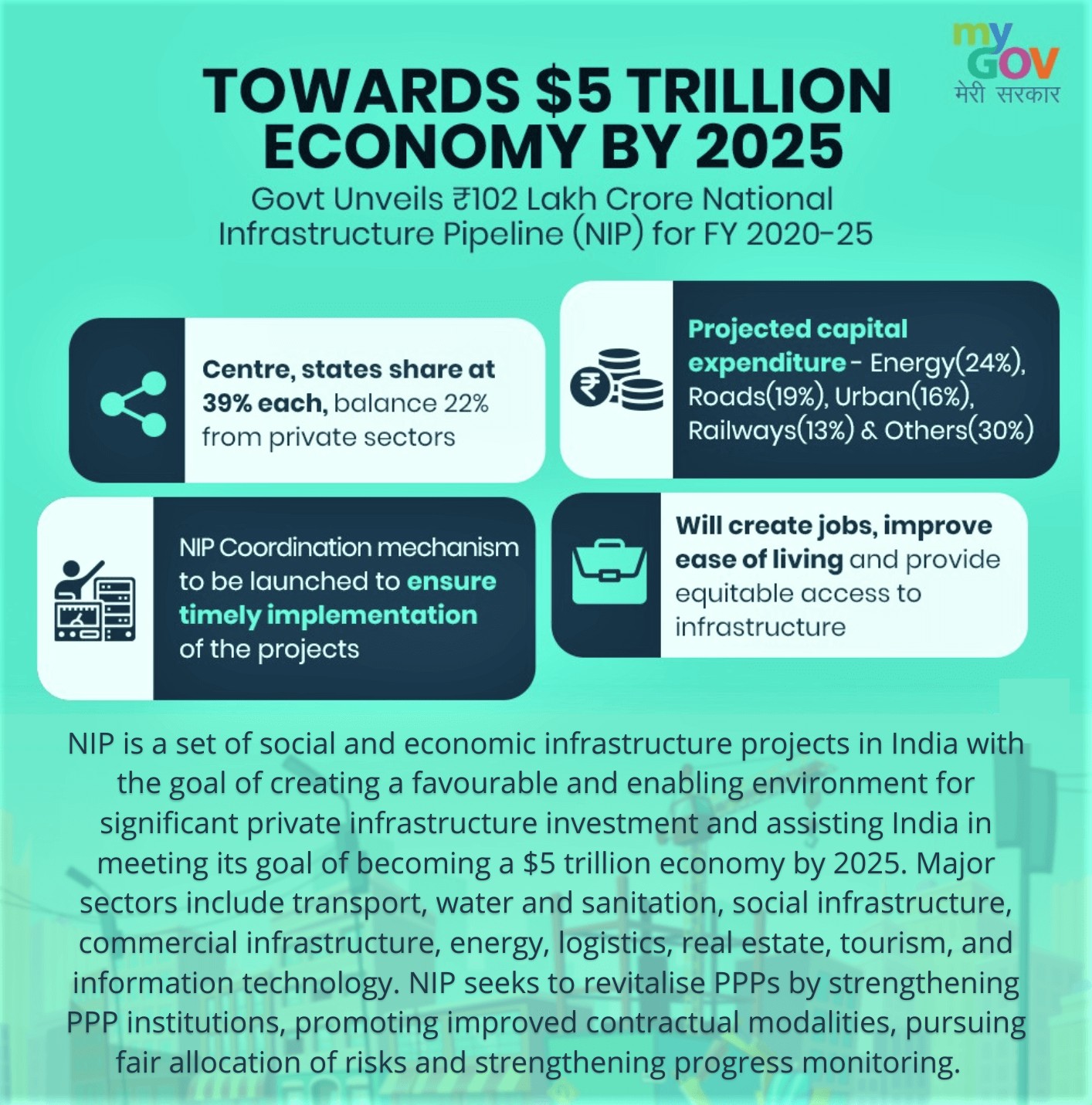

Many programs have been launched by the government to boost private investment in the country. In 2019, the government announced the implementation of infrastructure projects under the National Infrastructure Pipeline (NIP) with an initial capital of Rs 102 lakh crores over a period of five years starting 2020.

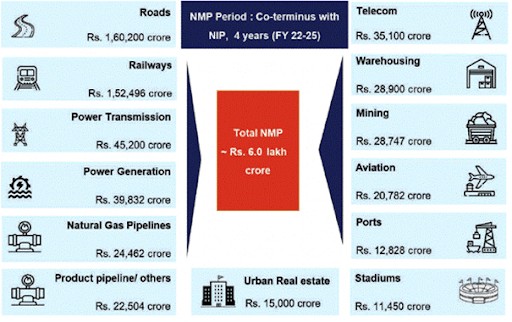

The implementation of NIP also implies the setting up of a new Development Financial Institution (DFI), monetisation of infrastructure assets through National Asset Monetisation Plan (NMP). To meet the NIP’s goals, the Finance Minister unveiled the National Monetisation Pipeline (NMP), which aims to raise ₹6 trillion (USD 81 billion) over four years, from FY 2022 to FY 2025, by leasing out state-owned infrastructure assets.

The deployment of all such major programs with the aim of expediting the process of privatisation and allowing private players to invest heavily in mega projects could have a range of impacts on India’s overall social and economic system.

The Need for Legal, Regulatory, and Conflict Resolution Systems

A major concern is that services offered by the private sector may get costlier for the end users. Once the government loses control over utilities, the general people will be affected by rising user fees imposed by operators of highways, trains, airports, power grids, and more. If charges levied on services are exorbitant, it will lead to exclusion of users and will not remain reasonable and affordable for all. Then there is also the fear that the government’s subsidy to the poor and needy may be reduced if tariffs increase. The infrastructure sectors are not only accessed by the affluent class, but by all. There are no specific guidelines or rules on how much tax will be raised on these assets and services nor enough clarity on checks and price limitations that the government will place on these private participants.

For instance, unlike airports, roads and trains, which are used by everyone including the poor and low income groups, even the poor—the fares, station entry fees, and costs for using public restrooms must all be considered in determining whether they will remain affordable to the masses.

Private investors owning and controlling these projects, it is suggested, would affect the interests of common citizens in the long run because there is not enough clarity in various regards. For one, the legal, regulatory, and conflict resolution systems are not explicitly clear. This calls for strengthening the standardisation of social, environmental, and labour aspects to prevent violations for profit maximisation. Secondly, there are concerns about the valuation models. The lack of recognisable revenue streams across various assets discourages diverse participation, and could potentially lead to vested interests and corruption. Lastly, no process for resolving disputes has been specified in the government’s approach.

For instance, in the case of India’s inland waterways where multimodal terminals are built, there are financial, social and environmental standards that remain absent. In the case of Sahibganj Multimodal Terminal in Jharkhand, a project funded by the World Bank, “the revised estimated cost is ₹4,633.81 crores.” The World Bank’s loan itself is approximately ₹2,376 crores of the sum.

The Sahibganj Terminal, for example, exhibits sunk costs of two other kinds. There have been heavy social costs paid by the local population, with around 485 families in Sahibganj being displaced for the project. Alongside this, there are costs borne by the environment. While the Jal Marg Vikas Project (JMVP) has been presented as an environmentally friendly project, the risks it poses to aquatic ecosystems and riparian communities remain underacknowledged.

The success of integrating private companies into mega projects will be measured by the quality of the infrastructure available and whether they will remain accessible and affordable to all. Development driven through private interests ultimately benefits only a few, leaving the core purpose of public goods behind.

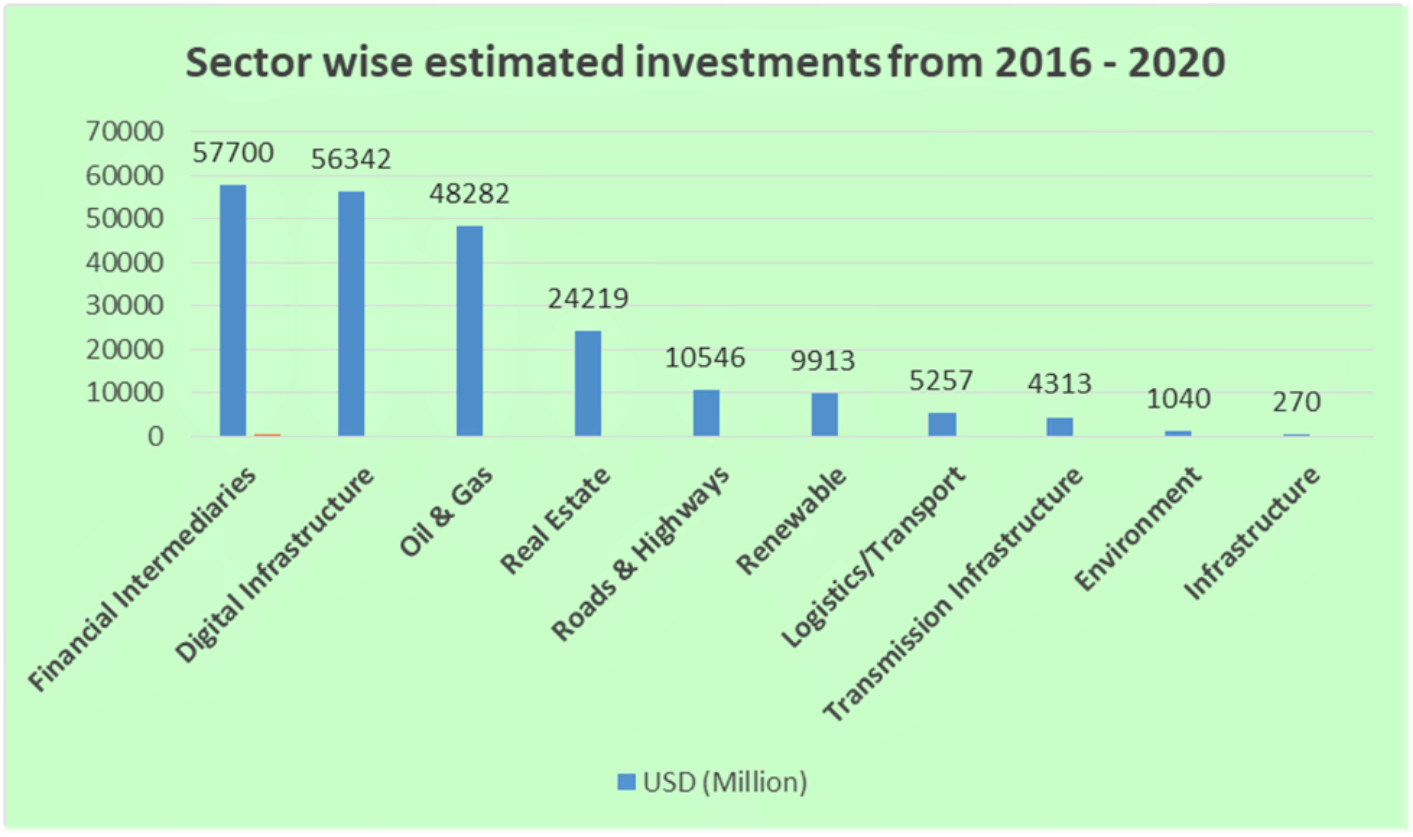

[Note: The data is gathered from public sources over a period of five years, from 2016 to 2020. Due to the limited scope of the study, the currency exchange rate used to convert USD into INR has been set at ₹74.1 per USD, which is the average dollar rate for the year 2020.]

Featured image is of infrastructure projects in producing crude oil and gas, roads and highways, and solar energy by private entities; courtesy: National Investment And Infrastructure Fund Limited, India Grid Trust, PIB

[…] This is Part Two of #FinancingDevelopment, a series analysing the finances behind India’s development journey, in collaboration with the Centre for Financial Accountability. Read Part One on the risks of private infrastructure projects here. […]