The Indian economy is the fastest growing major economy in the world. With rapid growth comes a rapid increase in energy demands. Given the need for protecting our environment, renewable energy is quickly gaining relevance. In fact, out of a power-generating capacity of 350 Gigawatts, 71 GW of India’s energy comes from renewable energy sources. The renewable energy industry is indeed the fastest growing energy-segment in the country.

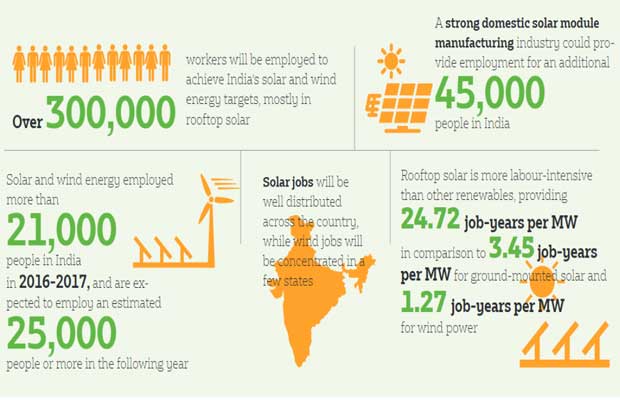

In addition to being environmentally conscious, the use of renewable energy increases the diversity of the sources used for energy production and enhances energy security, as its sources are practically inexhaustible. This becomes even more important for the less-developed areas of the country that do not have access to conventional energy sources. Moreover, as the renewable energy industry is more labour-intensive than the fossil fuel industry, it creates more jobs on average. It also makes economical sense; albeit being expensive to set up, renewable energy has negligible maintenance costs. A solar power system, for example, has an average productive lifespan of 30 years.

Today, with a 23 GW capacity, India’s solar power capacity has swiftly grown by almost nine-fold, from 2.5 GW in May 2014.

But despite the appreciable growth of the domestic solar industry, 80% of India’s solar capacity is imported in the form of Chinese or Malaysian solar panels, because Indian solar cells cost more. Consequently, cells cannot be domestically produced at a large scale by the fledgling industry. In comparison, the Chinese solar behemoth manufactures at rates subsidised by its government.

Are We Going To Waste A Gift?

Given these circumstances, the Directorate General of Trade Remedies has recommended an imposition of a safeguard duty (SGD) on the import of solar cells from China or Malaysia. This will be a 2-year imposition starting at 25% for the first year, 20% for the subsequent six months, and 15% for the last six months. It is meant to protect domestic solar cell producers from the overwhelming threat of cheap energy from its Asian neighbours. However, it is yet to be implemented because of petitions against its levy. If the introduction of the SGD in the Indian solar market is to see the light of day, it will go down as an ill-timed measure.

As discussed, Chinese solar cell manufacturers operated at subsidised rates. Recently, the Chinese government has decided to cut all subsidies for utility-scale solar projects. The resultant increase in production cost is likely to reduce demand by 40%. With China accounting for 50% of the global solar demand in 2017, prices for solar cells may drop by a whopping 35% in 2018, and a further 10-15% in 2019.

This decision by the Chinese government provides a great opportunity for India to boost its solar capacity by cashing in on the price-drop and importing as much as possible to quickly execute solar projects.

In this period, if the SGD were to be imposed, it will only counteract this opportunity. Its aim of protecting Indian manufacturers in the short-term will deny the country the opportunity to expand its solar industry cheaply and immediately.

Additionally, under the imposition of the SGD, capital expenditure necessary for solar projects is likely to go up by 15-20%. This will slow down the growth of the Indian solar industry. As a result, the number of installations of photovoltaic power plants will decrease. It has been estimated that in the coming four years, the solar industry will employ nearly seven lakh people.

At this stage, let us give credit where it is due. The government’s rationale behind their proposal to impose the SGD is indeed well-intentioned. Solar power tariffs are near the record low of ₹2.44 per unit. Any further decrease may push out the smaller players in the solar industry. The Indian producers will have the opportunity to increase their market share if the SGD is implemented. Yet, there are other considerations that retard the sustainable growth of India’s solar industry which has been disregarded.

The Sustainable Path Forward

The imposition of the SGD will not only lead to the country losing a great opportunity to capitalise on the immensity of Chinese production and will raise the cost of increasing the country’s solar power capacity. Given the government’s 2022 target, it will also put a stress on a developing industry that is unprepared to cope with the sudden increase of business and its concomitant higher expectations of quality.

In contrast, with the high demand for solar power in India, the short-term influx of cheap panels from China might temporarily reduce business for the domestic producers, but it will not push them out completely. In fact, the increase in solar installation projects across the country may even lead to increased employment across the sector.

The domestic solar industry needs to develop, but not through duties on imports. Sound development requires an efficient system to store energy, which is something that India lacks in. 15-20% of the energy produced from renewable sources is, in fact, lost due to inadequate storage facilities. In its stead, the government should provide subsidies that facilitate large-scale production, invest in research and development, which is required to continue to improve this technology and build efficient storage facilities.

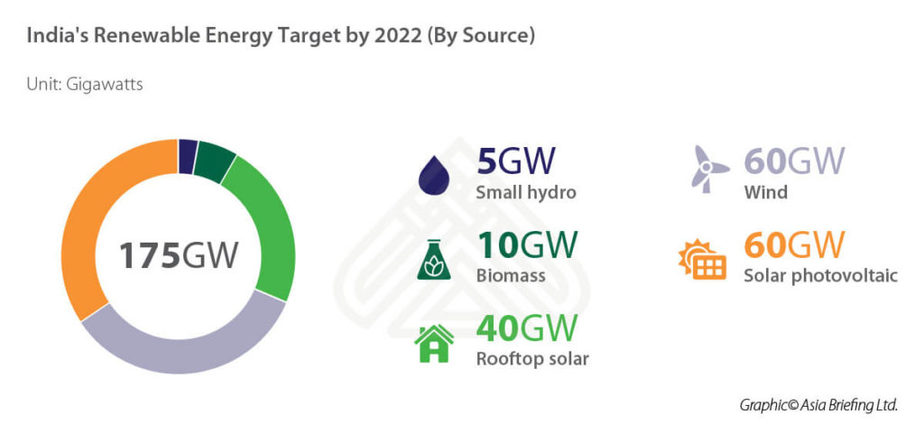

The government’s goal of 175 GW of renewable energy by 2022 is definitely an ambitious one. India’s current capacity for renewable energy is only 71 GW. However, as explained, in the last few years, the solar sector, in particular, has witnessed immense growth.

Long-term domestic energy goals can be better served by investing in better research on solar panel efficiency, better manufacturing practices and subsidies for solar cell producers, rather than a tariff on solar panel imports. So while the 2022 goal of 100 GW of solar energy is still ambitious, it is not entirely impossible if the imposition of the SGD is prevented.

[…] You May Also Like: Eternal Sunshine of Spotless Energy: Domestic Growth Through Safeguard Duties? […]