Over the four years spent traversing the Himalayas in Uttarakhand and speaking with agricultural communities, Chinmaya Shah had made an astute observation about cropping patterns. A Project Coordinator with Chaukhutia-based Institute of Himalayan Environmental Research and Education India, Shah noticed that it had become a rarity to find madua, also known as ragi or finger millet, being cultivated anymore. The Agricultural Census’ statistics match his observations about this historically popular crop. From over 11,000 hectares under cultivation in Uttarakhand in 2005-06, madua was being grown in only a little over 9,000 hectares in 2015-16.

“After harvest, the madua requires an intensive pounding process to peel it off from the husk,” explains Shah. “It has some 1-2 layers that need to be removed to get to the valuable grain. This labour-intensiveness is one of the reasons why many cultivators have moved away from what is a traditional pahadi crop.”

In an attempt to make madua lucrative again, the Uttarakhand government applied for its Geographical Indication (GI) tag this April. The application includes ten other food items unique to the state, including Rhododendrons, red rice, and pahadi toor dal. GI tags represent the geographical uniqueness of a product; they certify that the product has originated specifically from a particular region, and is of a certain standardised quality. In India, the Geographical Indications of Goods Act, 1999 lays down the legal architecture to register a GI. Ranging from Darjeeling Tea to the oranges of Kodagu, Jammu and Kashmir’s saffron, and Gujarat’s Kesar Mangoes, over 400 GI tags are currently registered in India, including those for handicrafts, art, and manufactures.

“GI tags are a great way to highlight local produce at national and international markets, and it definitely evokes a sense of pride and identity for those associated with cultivating it,” Shah continues. “But, how much does such a tag help [overcome] the backend agricultural challenges that have long-existed in cultivating those crops?” While some Indian GI-tagged products have led to their international popularity, they are plagued by a limited ecosystem for helping farmers with competitive prices, and the threat of reducing biodiversity in the pursuit of particular products.

Higher Prices, But Not Everyone Benefits

In 2007, Kerala’s Navara rice that is grown in Palakkad district received a GI tag. This traditional, short-variety of rice is grown without any fertilisers to keep its various medicinal properties intact. With the tag, it was expected that the crop would be able to fetch higher prices, thereby incentivising farmers to cultivate this traditional rice variety. But, things didn’t go as per plan.

Even today, many farmers remain unaware of the GI tag that their crop has now been associated with. This is primarily because of a missing step in the registration—the GI was registered without prior consultation with local stakeholders to agree on standardised practices for growing this rice.

The registration for GI tagging is a people-centric process, which requires only an association of persons, producers, an organisation, or an authority to represent the interests of those producing the said goods and then file an affidavit on their behalf. Experts then run a thorough scrutiny and examination of the products. Post that, the association and the crop’s growers have to be on the same page about the common adoption of practices to grow the product, which would then ensure a standardised quality, further confirming competitive prices in the market. In other words, anyone in the said geographical region can grow or create the product using the GI tag—even beyond the Association that initially registered it—as long as it meets the quality standards commonly decided upon.

But, with limited awareness, only a few aware rice farmers in Palakkad have been able to create a dedicated customer base and export orders, with some selling their produce as high as ₹300 per kg. Uninitiated and small-scale farmers receive just about ₹30 per kg for the same Navara rice.

This push to get a certain product into the larger market could benefit from maintaining a careful balance with local markets. Anshul, a co-founder of Himachal Pradesh-based Shunya Farms, a leading organic and permaculture farm in the region, speaks of his experience. When he lived in Himachal Pradesh, he found that the local markets never had the famous Kinnaur or Spiti apples of the state. “Those were being supplied to major cities in the country and abroad, and what we had locally were actually imported from Chile!” he says.

When big pushes to incentivise certain products happen, it also reshapes the lives of local communities. And in times like the [COVID-induced] lockdown, we have seen how precarious the international market can be, and how important it is to have rich local markets to sustain local populations.

—Anshul, Shunya Farms

For growers to benefit from better prices and markets—both internationally and locally— the tag alone would not suffice. An ecosystem supporting the farmer’s knowledge and decision-making would be needed, along with better agricultural technologies.

Shifting Focus from the GI Product to How It is Produced

“If the motive is to incentivise madua cropping, the focus has to be on the harvest and post-harvest of the crop, because those processes remain labour-intensive whether or not the GI is registered,” Shah suggests. The same problem exists with Navara rice too. Even at premium prices, research from 2021 found that prices were not outweighing the costs of growing this labour-intensive traditional rice crop.

This labour dependency on growing a product could also benefit from low-cost modern interventions. “In Uttarakhand, when people process madua in the traditional Jhanghar (Kumaoni for handmade and labour intensive stone mill), they would often use the same device for pounding other grains. This would often cause a mixture in the flour, due to which the traders offer a lesser price than the market price. Low-cost, easily accessible innovations and machines are needed for the people to meet the quality of the product along with the GI certification,” adds Shah.

A similar problem of costs of production outweighing the high prices resonates with Darjeeling’s Tea as well—India’s first GI-tagged product. The tag has certainly helped improve the quality of the tea (through strict rules of chemical use and new tea leaf-plucking methods) and boosted its allure in international markets. Yet, the costs of producing and marketing Darjeeling Tea still outweigh these benefits, indicating that more support is needed in marketing GI-tagged produce.

Also Read: Brewing in Uncertainty: The Lives and Livelihoods of North Bengal’s Tea Plantation Workers

In the best-case scenario wherein farmers may have a supporting ecosystem alongside the GI tag for their products, a sequence of events leads to a troublesome reality. As more farmers find an incentive to grow a certain GI-tagged crop, it could lead to monocultures, thereby reducing the biodiversity of said region. This is not as far-fetched a reality as it may seem, as the case of Mexico’s GI product, tequila shows us.

A Delicate Balance Between Incentivising Monoculture and Maintaining Biodiversity

The popular alcoholic drink distilled from agave has held a geographic indication since 1974, and is produced exclusively in Jalisco, one of the five Mexican states. But over the years, as the drink became a popular choice in the North American market, the ecological and cultural factors—or terroir, as French literature puts it—underwent a gradual change. As more farmers shifted to growing agave, there was a decrease in the genetic diversity of species and varieties. In time, traditional knowledge and techniques waned, what with the incidence of pests the usage of pesticides increasing to ensure high productivity of what has now become an invaluable plant.

“When such changes to the biodiversity occur—whether through an intensification of the GI tagged product or even other climatic reasons—the GI-tagged product itself faces a threat of losing its uniqueness, its flavour, and everything that made it special,” comments Anshul.

Additionally, in the case of tequila, the smaller producers were slowly moved to the sidelines, as larger industries entered, creating an imbalance of power and distribution of costs and benefits. Closer to home, the production of Darjeeling Tea also shows an unequal distribution of costs and benefits. The dominant production system in Darjeeling consists almost entirely of large-scale tea plantations that span 200 hectares per plantation on average. The role of the local communities is limited to plucking leaves. Further, converting natural ecosystems to monoculture agriculture—like tea plantations—leads to the loss of habitat and biodiversity, something which has been documented in the case of Darjeeling Tea. In fact, a 2021 research paper now shows that in order to increase the biodiversity of the region, tea plantations should introduce native shade trees along with others that can help create ‘sub-habitats’, which make plantations ‘biodiversity-friendly.’

As GI tags attain popularity and move towards great success, it is imperative to include communities and their traditional knowledge systems of growing and managing the various products. Apart from madua, Uttarakhand’s latest GI tag propositions also include the state’s official tree—rhododendron or buransh. Unlike the other products that are majorly grown on private lands, this flower is accessed commonly from the forests between February and April for its medicinal properties popular amongst pharmaceutical industries, besides being used locally to prepare squash and chutney from the rhododendron flower.

Where increasing interest and demand for the tree may accelerate due to the upcoming GI tag, controlling its over-extraction is of key concern. This is where Uttarakhand’s Van Panchayats must be roped in during the GI tagging process. Research has already documented the various methods adopted by Van Panchayats to monitor the tree’s sustainability—yearly rotations in the areas from where the flowers are harvested, and allowing only 60% of a tree’s flowers to be plucked while the remaining blooms are left for regeneration.

Communities and farmers need to be an important stakeholder in the pre- and post-registration GI tagging processes to weave in decisions to protect traditional knowledge systems and ensure quality and sustainability of the GI-tagged products.

Uttarakhand’s GI tagging proposition comes at a time where there is the advantage of hindsight of the consequences of other GI products. While it is heartening to see that the Himalayan state has proposed the tags for some traditional crops that seem to be slowly disappearing, for maximum advantage, the entire process of growing the crops needs to be accounted for—ranging from involving the communities, local associations, and NGOs in the pre and post-registration process, all of which needs the support of low-cost agricultural innovations as well as adequate marketing of the products at hand. Devoid of those, perhaps Shah’s observation of dwindling madua cultivation in Uttarakhand may prove to be an unchanged prophecy unchanged in the coming years.

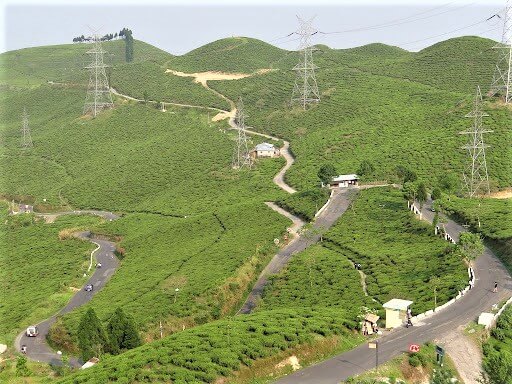

Featured image of ragi millets being cultivated in Uttarakhand via Twitter