It was 2 am when Alahrakha Islmailbhai Dhimar’s phone rang in the middle of September 2021. Gujarat was reeling under floods, as he strained to hear the voice at the other end over the rain lashing down on his home in Tukda Gosa, Porbandar district. Large evacuation and rescue operations were underway, and Dhimar was being called to participate. The National Disaster Response Force had spent over 12 hours looking for a young man lost near the waters of Gosabara wetland—just a few kilometres away from Dhimar’s home—but to no avail. Dhimar and his neighbours hopped on their fishing boats to head into the wetlands’ waters which they knew so well. Within twenty minutes, the young man was found and returned safely.

Over the years, when there would be floods, Dhimar and his fellow Macchiyara community members—who are traditionally small-scale Muslim fishers— have helped rescue those stuck at sea or the wetland, besides recovering bodies of those who didn’t make it out alive. But in May 2022, the same life-saving Macchiyara community approached the Gujarat High Court to seek death through euthanasia for their 600 members. The petition signed on behalf of the Gosabara Muslim Fishermen’s Society alleges discrimination against Macchiyaras in accessing the Gosabara wetland and sea waters since 2016 – access that is crucial for sustaining their fishing livelihoods– while the Hindu fisherfolk seem to be allowed to do so indiscriminately.

“We met various authorities and wrote to them too, from the District Magistrate’s office to the Fisheries Department and the head of the Revenue Department. We sought help for alternate livelihoods and securing our government entitlements. We even wrote to the Chief Minister and the Prime Minister. But when the matter did not move at all, we have now petitioned for death at the High Court,” says Dhimar, speaking on behalf of the Macchiyara community who filed the petition “A person will only be ready for death when their rozi-roti [livelihood] is finished. Ours has died in the last six years”, he adds, poignantly.

While this recent development at Porbandar may appear to have left a communal aftertaste between Hindu-Muslim fisherfolk, the undercurrents present a myriad of ecological contests and caste-class intersections amongst Porbandar’s small and large-scale fishing communities. Perhaps more than religion itself, this sociocultural context defines access to marine and freshwater ecosystems and livelihoods from its produce.

Caught Between Protecting Birds and Fishing

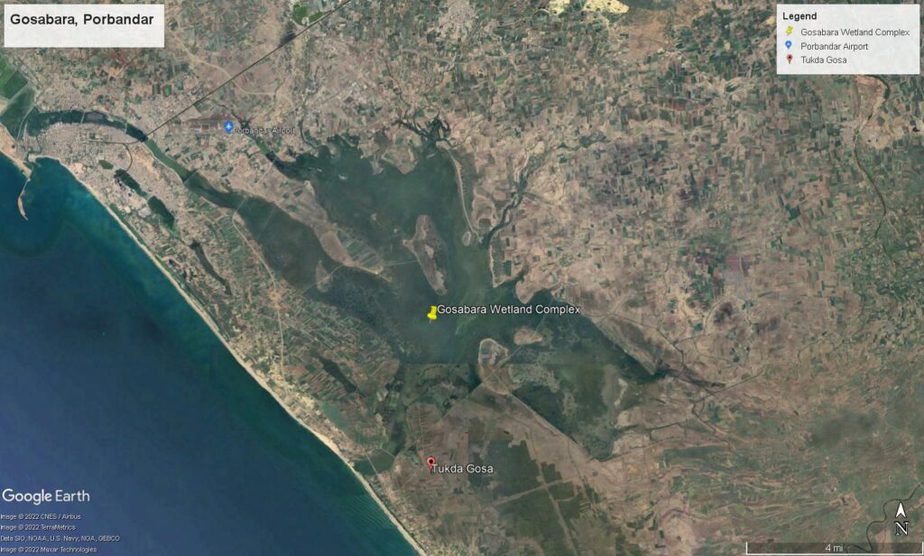

“What is currently happening in Porbandar is a result of conflicting interests between various stakeholders in the Gosabara wetland,” says GA Thivakaran, Chief Principal Scientist in Coastal and Marine Biology at the Gujarat Institute of Desert Ecology (GUIDE). His comments mirror developments of 2015, where the Gujarat High Court directed the state government to decide whether this wetland should be declared as a sanctuary or not. This came after a Public Interest Litigation was filed the previous year, which claimed that many migratory birds visit the wetland, and face severe threats from fishing since “they get caught in the net”, along with active poaching of the birds.

Spread over 100 sq km, the wetland has a unique ecology. In its south, it has the Karli freshwater natural reservoir, fed by four seasonal rivers, and the north of this wetland is marked by Karli Tidal Regulator which attempts to prevent the saline water of the hugging Arabian Sea from entering this freshwater body. “The combination of salt-water and freshwater supports both marine and freshwater birds at the same time which makes its ecology a rich one,” says Thivakaran. An estimated 112 species of birds are found here.

Till the state government mulls over making this area a protected one or not, the Court in 2015 had ordered that no fishing or hunting activity would be permitted. Six years later, the status of the Gosabara wetland is still undecided. In the meanwhile, the Bombay Natural History Society declared the wetland as an “Important Bird Area” in 2017, and in February 2022, a two-day bird census was conducted. Fishing has remained banned through the years and the 87 households of Macchiyaras—the only community here who were dependent on the wetland for fishing— have been adversely impacted.

The Macchiyaras of Gosabara Wetlands

“We have been fishing in the meetha paani [literally translating to “sweetwater”, by which he refers to the wetland] for at least five generations. We’d fish for about eight months between July to February when rainwater would feed the wetland through the streams,” says Dhimar. The Macchiyaras are traditional fishers who use small and non-mechanised boats to venture the waters. To fish, they use gillnets—vertical panels of the net, or the Pagadiya method—fishing on foot with nets.

“Wetland fishing is fundamental to their [Macchiyara] cultural heritage,” says Dr. Derek Johnson, a professor at the University of Manitoba who has conducted doctoral and post-doctoral research on Gujarat’s coast and small-scale fishers.

Their oral history states that they came to the coast of Gujarat many generations ago by following rivers from Sindh. They were originally inland fishers who learned to fish in the marine environment at the end of this migration. As a consequence of this history, they retain a preference for fish caught in streams and estuaries. Banning them from fishing in this wetland is thus not just a livelihood issue, but also an identity issue.

— Dr. Johnson

With the probability of the region being declared a bird sanctuary, the Macchiyaras find themselves entangled in a battle that pits them against the ecology of the wetlands. But as Thivakaran points out, this might be a false dichotomy. “There is no doubt that the wetland has one of the richest avifaunal [bird] biodiversity of North India. And, when we were doing a survey in the wetland in 2016, we also observed a few poaching incidents, so the cause of worry [of the High Court] is not entirely without basis. But, the overall fishing that we witnessed there was only by small-scale traditional fishers, who do not impact the ecology of the wetland much. In fact, moderate fishing promotes healthy ecology in the water,” he says.

Since 2016, in the absence of any other livelihood option, the community has been forced to sidestep the ban to enter the wetlands, for which they have subsequently been arrested. Some others chose to shift from inland fisheries to a similar yet vastly different sector— marine fisheries.

From Inland to Marine Fishing, the Question of Rights Remains

This shift was accompanied by new investments for Macchiyaras. “The sea needs bigger boats than the ones we use for inland fishing, so we bought new boats. It’s an expensive proposition, so some of us took loans from relatives, others mortgaged jewellery,” says Dhimar. After the initial investments, marine fishing was proving to be a good option, where earnings through the catch could range from ₹1000 to ₹10,000 on a good day.

While this shift helped sustain their livelihoods, in a few months, the communities found their fishing licences needed to get renewed. Officially, no fishing licences have been renewed since the ban in 2016, following circulars from Porbandar’s District Magistrate’s office. In effect then, all those Macchiyaras who held legal permits to enter the water for fishing could not make legitimate entries anymore without renewals.

After years of constant discussions with the Fisheries Department, the community managed to renew their fishing licences in April this year. But again, it came with a catch. “We have permission to fish, but not to park our boats in the sea. This will require a signature from the District Magistrate, which has not happened so far,” Dhimar says.

Because of this missing link, the Macchiyaras began working in larger fisherfolk’s boats as labour. They fish for them and pay the owners of the boat some money as tenants.

When we were fishing and selling on our own in the wetland, each kilogram of fish brought us about ₹100. Now, after paying the thekedaar [contractor who hires them], we are getting about ₹10 per kg. But we keep thinking that at least we are getting some income, and so we continue.

— Dhimar

Pradip Chatterjee, Convenor of the National Platform for Small-Scale Fish Workers (NPSSFW) reminds that such discrepancies between the right to fish and the right to sale are not isolated.

Across India, while small-scale fisherfolk can catch the fish, they sell it via auctions to large contractors. These contractors offer very low prices, like around ₹32 per kg in Madhya Pradesh. This is why, the rights of small-scale fishers—the right to catch and sell both— have to be ensured and protected. NPSSW also issued a statement requesting the government to redress the grievances of the Muslim fisherfolk of Gosabara earlier in May.

As Gosabara’s fishers moved from inland fishing to marine fishing, they faced another challenge in the open seas—fierce competition from large fishers and trawlers. It is in these interactions that the issue seems to have taken a communal turn, while a class-caste angle seems to weigh heavy too.

Competing with Large-Scale Trawling, Deepening the Exclusion

In India, while the proportion of mechanised boats is lesser than the traditional non-mechanised ones, their catch surpasses those of traditional boats by a large margin: as of 2015, just 25% of the mechanised boats produce 75% of India’s fish catch. In Gujarat, such a push for mechanised, large-scale fishing began in the 1960s, with the state promoting growth-oriented interventions in the fishing sector. As trawling became economically valuable but ecologically unviable, small-scale fishers in the Gulf of Kachchh region started facing the loss of livelihoods due to competition of the coastal space with industries. This became evident in documented conflicts between small-scale fishers and trawlers towards the end of the 1960s.

So, who are these trawlers? In Porbandar, they mostly come from the Kharva caste, a Hindu fishing community that has dominated the more lucrative processing and international trading sectors of the local fishing economy, along with a few other Hindu groups and the odd Muslim exception. As Dr. Johnson writes of his research in Porbandar’s neighbouring district of Junagadh in the book Conflicts, Negotiations, and Natural Resource Governance, the Kharvas’ family enterprises own multiple trawler vessels, “as many as 40 per enterprise,” while even the most successful small-scale fishing based families of Macchiyaras cannot “approach the economic clout of the urban-based trawler owning families.” In fact, the Macchiyaras often depend upon the Kharvas, for processing and other upper links of the fish market chain.

“While we [small-scale fishers] have been facing the problem of permissions and licences to enter the ocean, the same is not the case with the larger fishers and trawlers of Kharvas. They are much more connected than us, they have discussions with the Chief Minister’s office with such ease, while we think twice before even meeting the District Magistrate!” says Dhimar, highlighting the social capital that the Kharva community might be benefiting from in entering the marine waters, while the Macchiyaras have been running pillar to post for the same.

“Gujarat’s fisheries are in trouble not because of small-scale fishing in inter-tidal spaces but because of rampant trawler-driven overfishing and coastal zone industrialization. This is part of the structural disadvantage done to the Machhiyaras,” Johnson adds. “In most villages, they have no access to schools and poor access to administrative, legal, health, and other government services. They are also subject to social discrimination. Kharvas, in contrast, are an important coastal community that has used intensive fishing, processing, trading, and involvement in other non-fishing economic activities to climb the economic and status ladder since the day’s several generations back when they were treated analogously to Dalits.”

Echoing a similar sentiment, Dhimar reminds us that it’s the discrimination from the State that has left the community disappointed, more than the discrimination from other communities. “Amongst us, the relations between Hindus and Muslim communities are very cordial,” he continues. “We go to each other’s wedding functions too. But, when it comes to the benefits of fisheries schemes from the administration, we feel that we are discriminated against [by the administration], while the Kharavas have been able to make use of them.”

“What is currently happening in Porbandar is not necessarily a communal issue, but that of exclusion [of the small-scale fishers],” says NPSSFW’s Chatterjee. “We have seen such exclusion in other parts of the country within the fishing sector too, which are mostly of one caste against another. In the case of Porbandar, as a strategy further ahead, NPSSFW has also planned meetings with Kharvas along with Macchiyaras in the near future.”

The government’s push for economic growth in the fisheries sector is bound to bear fruits unequally, depending on the caste, class, and religious structures of power involved. Clubbed with the intent to protect birds’ habitat, the minority Macchiyara community finds themselves pushed into a corner, an exclusion that has resulted in a desperate plea to put an end to their suffering via euthanasia, a plea that is yet to be admitted in Court. “It feels like mental torture, where after stripping away our livelihoods and access to marine and inland fishing, the administration hopes that we would leave the place,” Dhimar laments. “How can we leave a way of life?”

Featured image of Modhva fishing village in Gujarat (for representational use). Image credits: Koshy on Wikimedia Commons.