In a country like India, with a rapidly growing population of young people and rising inequalities, the Right to Education Act (RTE), enacted in 2009, serves as a legal and constitutional safeguard for children in the age group of six to fourteen years to avail free and compulsory education. Since its enactment, the school enrolment data reached a maximum of 114.54% in 2016 (school enrolment data can exceed 100% due to the inclusion of over-aged and under-aged students because of early or late school entrance and grade repetition) from 96% in 2009. While the RTE has made considerable progress over the years, there exist several gaps and loopholes whose burden is thrust on children from marginalised communities like Om and Swati.

Back in 2016, when India recorded the highest school enrolment, Om and Swati were in school, and their enrolment was part of this record percentage. The RTE has ensured they both have access to free and compulsory education—irrespective of any geographical, economic, or social boundaries or identities they carry—which can positively impact their abilities to enhance their well-being, become economically productive, develop sustainable livelihoods, contribute to peaceful, and democratic societies. Unfortunately, while accounting for the record percentage, the factors outside of their classroom walls have not made it to any data gathering exercise.

This is the story of Om and Swati, which represents countless challenges and varying realities that children from marginalised communities face in continuing education.

◯◯◯

Om Kumar, 20, migrated to Mumbai in 2014 from a remote village near Darbhanga, Bihar. Along with his father, they settled in Mumbai’s Worli Dairy Slum. “I got admission in an English Medium Municipal School. Before that, I was in my village where I had studied in Hindi medium,” says Om. “Starting mein kuch samajh nahi aata tha ki textbook mein likha kya hai” [When I started, I could not understand anything since the textbooks were in English]. Over time, Om realised that all his classmates were also migrants and they came from either Marathi, Urdu, Tamil, or Telugu mediums. They also faced the same language barrier when they came to Mumbai. “Mere dost hi mere Google translator aur dictionary the” [My friends were my Google translator and dictionary whenever I needed help with translations] recalls Om.

In Greater Mumbai, 1,959 slum settlements have been identified, with a total population of 6.5 million, which forms 54% of the city’s total population. Mumbai’s slums represent India’s issues concerning overpopulation, drinking water access, pollution, land space, poverty, unemployment, health, and waste disposal.

A Day in the Life of Om—Similar, Even 7 Years Apart

At 4 am, Om steps out of his 7′ by 8’ room-sized house to deliver Sunny Brook’s Dairy Farm ‘fresh A2 milk’ to 30 families across Mumbai, including my family. He returns home by 7 am to fill water, cook himself breakfast, clean the house, and get ready to leave around 10 am to Veggyums [the restaurant where he works]. On his feet the entire day at the restaurant, he manages raw materials, building customers, packaging and delivering parcels, catering business, and as a cashier. He also juggles between two other jobs—selling pets and delivering vegetables at door steps. He occasionally finds time to study for his college courses between 7:30 and 8:30 pm. “My sister recently got married, and my father has taken a huge loan. His salary is far from sufficient, so I feel the need to work multiple jobs to support my father financially,” says Om.

A day in Om’s life is not significantly different from when he attended school. As a teacher, his attendance was a huge concern for me when I taught him back in 2015. He would attend school 60% of the days, as the remaining days were spent searching for jobs to manage his school and tuition fees. “Each day during my schooling was a dilemma,” Om shares.

On one hand, I felt privileged to be the first-generation learner in my family, although it came with considerable pressure to study hard and get better marks because of the sacrifices my parents were making, and the hope they pinned on me to take the family out of poverty. On the other hand, I felt I was wasting lot of time in school, which I could have utilised to earn money to support my father financially—going to school put a lot at stake! I do not aspire to be wealthy. I desire a life where my family is debt-free of all kinds of loans.

—Om Kumar

Mumbai’s Urban Disparity and Om’s Aspirations

Mumbai’s wealthy neighbourhoods are unique—areas with extreme poverty are located within the affluent areas. This inequality between the rich and the poor is starkly evident where Om resides. What concerns Om the most regarding this disparity is the unjustified privilege that the rich hold while his community members are disregarded completely even when both share the same neighbourhood. “At around 6 am, I stand in a long queue every day to fill water provided by the BMC. The entire community stands holding buckets, even during the heavy rains.”

“I cannot see the sunrise from my community because of the skyscrapers in my neighbourhood.”

—Om Kumar

“While I stand and wait for my turn, I see on the opposite side of the main road a few Mercedes, BMW, and Porsche are washed imprudently with incessant clean water,” says Om while sharing his resentment towards the disproportionate share of resources. “How can one justify this disparity living in the same neighbourhood?”

India’s richest 1% hold more than four times the wealth held by 953 million people who constitute 70% of the country’s population. The extremely rich and powerful are profiting from pain and suffering. This is unconscionable. Some have grown rich by denying billions of people access to vaccines, others by exploiting rising food and energy prices. They are paying massive bonuses and dividends while paying as little tax as possible. This rising wealth and rising poverty are two sides of the same coin, proving that our economic system functions exactly how the rich and powerful designed it to.

Swati’s Troubles with Accessing and Continuing Education in Rural India

In India, the tribal communities or the Adivasis live in far-flung forest areas that are often not easy to access due to regional terrains and remoteness. Traditionally, tribal life and livelihood are dependent on forest resources, which translates into rare instances of dependency beyond the community. As per the National Sample Survey Report (71st round), more than 12% of rural households in India did not have any secondary schools within 5 kilometers.

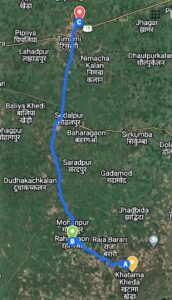

Swati Uikey, 21, from Khatama Kheda village in Madhya Pradesh’s Harda district corroborates these findings while narrating her experience in her native Gondi language. “Naa Mummy Papa rantaee jainare nede 12 mahina kaam kyator”, she says, meaning that both her parents work on farms as labourers throughout the year. “They leave for work at 9 am, and return for lunch at 1 pm; around 2 pm, they leave again for the farms and return by 8 pm. Post dinner, at 9 pm, they are back to the fields, returning only at 7 am in the dawn. That’s their daily schedule for the year, working for 20 hours on the farms [and returning only for meals]”.

The nearest school was in Rahatgaon, 8 km away from my home. There was no transportation, nor could my parents afford any private vehicle. Hence, for the ten years I was enroled in school, I walked for 8 km every day to reach school and another 8 km to return. I remember during school days, I would wake up every day at 4 am to study till 6 am. This was the only time I had during the day. After sunrise, I needed to do all household chores alone. At 8:30 am, I would leave with my family to work in the fields. From there, I would go to attend school to at 11 am. I would return home in the afternoon, cook lunch and dinner for my family and take care of my younger siblings.

—Swati

Managing both household chores and studies was very difficult, which in turn deprioritised Swati’s studies over work. She studied till grade 10 because the nearest Secondary School was in Temarni, 25 kilometers from her place. Enroling in a secondary school would have meant walking for 8 kilometers, first to reach Rahatgaon to find a bus stand; then waiting for an indefinite time for a bus to come; and then travelling 17 kilometers further to reach Temarni. The National Achievement Survey (NAS) 2021 report reveals that half of India’s students go to school on feet and only 9% opt for school buses.

“The biggest issue was not the travel. Since I live in a forest area, with a lack of street lights and a scarce population, travelling back alone in the dark is unsafe—eve-teasing, abuse, and harassment of girls and women on the roads is rampant in and around my village. I have been a victim of it multiple times, and it is traumatising,” Swati says. Staying away from home all day would also mean that her responsibilities at home would fall on her already overtaxed parents. According to Census 2011, rural children aged 5-14 (8.1 million) are more likely to be engaged in work than urban children (2.0 million).

She adds, “Nede kamaai kisi nedeii lakyator” [Whatever my family earns from their daily labour, they put it back on the farms]. The entire family is engaged in labour, especially younger boys like her brother who start as young as eight years old. Swati too goes to the farm, but only occasionally, to help with spraying pesticides, insecticides, irrigating land, and weeding. A common reason why children work in the fields is the practice of bonded child labour. “A child engaged in slavery, who gives his labor against the amount taken by his family as an advance, is known as a Parkhiya in the Madhyanchal region of Madhya Pradesh. Parkhiyas provide their labour to the money lender against the loan taken by the family for reasons such as health emergencies, marriage of daughters, or death rituals.” Children are not free to leave bonded labour unless their families repay the loan. Families are forced to sign an agreement with the money lenders under which, unless they repay the amount and interest taken, they cannot leave work. “Children spend their entire childhood and adulthood working daily for 14-16 hours as bonded labour and face all forms of exploitation and violence,” Swati shares.

To break this cycle of school dropouts for other children in her community, Swati has joined the Udaan Fellowship offered by Synergy Sansthan. Through the fellowship, Swati is engaged in sensitising and empowering girls and women in her community to promote education and fight against eve-teasing, abuse, harassment; this way, she hopes they can complete their education journey, something she could not fulfil.

◯◯◯

Back in 2016, as India was witnessing record statistics for school enrolments, the inequity and oppression that marginalised children, such as Om and Swati, experienced outside their classrooms on the daily differed vastly. Despite their different realities, when Om and Swati entered their classrooms, they were taught the same syllabus, held similar books, read similar stories, solved similar problems, and learned similar concepts, albeit in different languages. The enrolment data can tell us whether Om and Swati were attending school regularly or not, but what will continue to be invisible, intangible, and incalculable in the world of statistics are the hardships they endure. Until these problems are accounted for, marginalised children will continue to suffer, and the RTE’s statistics will continue to be lauded for recording high enrolments. Om and Swati’s experience illustrates that even the RTE’s success in 2016 was unable to account for the challenges.

What matters is where the children come from. It matters what their gender is or whether they belong to a particular class or caste. It matters where they live, in a remote tribal village or in an urban slum, and who they are surrounded by. It matters what they have and what they do not because it dictates the inequities they need to confront in order to justify their place inside the classroom. Where they come from and their status in society decides the kind of unseen battles of oppression they need to fight outside of the classrooms—oppression that is visible and invisible, internal and external, individual and systemic, internalised and transferred.

While the success of high enrolments is largely attributed to the Right to Education (RTE) Act, staying in schools has not been easy for children, in both rural and urban India. Is it then fair to expect that what is worth learning for Om in an urban setting will be the same for Swati in a rural context? Could our schools be aware and inclusive of the diverse factors that marginalised children experience outside their classrooms that affect their access to education? The Right to Education Act, which makes education a fundamental right of every child in our nation, needs to go beyond free and compulsory education to enable inclusive and fair education at the margins. While focusing on enrolments, the inequities and oppression that challenge every child, whether enroled or not, cannot go unaddressed.

Featured image: Children at their school sitting outside a locked room; Courtesy Teach for India.