“Grassroots, systemic, holistic, scalable”—there is no dearth of descriptive buzzwords when it comes to the work non profits do within the development sector. However, while overuse may have rendered the meanings of these words shallow, there is one striking commonality linking nonprofits within the sector—their resolute pursuit to advocate for and empower the underserved.

This is the linchpin that binds together government actors and civil society in an enduring bond. This relationship beckons us as citizens to learn from it, and leverage the powerful potential of advocacy to challenge systemic development issues.

To engage in advocacy is simply to participate in the democratic process and influence public policy. At its core is the desire to work with the system to design large-scale reforms and to assimilate diverse perspectives into the process of policy design. A sweeping term, advocacy encompasses everything from formal report submissions and initiating Public Interest Litigations (PILs) to informal conversations, building civil society groups, and capacity building for government and non-government actors alike.

Nowhere else is this mediation and cooperation better used, or needed, than in the education sector.

Take, for instance, the preceding four articles of this series, where we explored the nuances of reforming public education systems in India. We covered the need to redesign curriculum, improve teacher-training processes, facilitate data-driven governance, and bring parents into the folds of the education system. Each one of these aspects is possible through leveraging the critical—and hard-earned—partnership between government and non-profit actors, a key facet of ‘development’ to end this series on systemic reform with.

What Impact Does Advocacy Really Have On Education?

“Public policymaking is a process, rather than a single, once for all act,” notes Richa Singh in the Oxfam India Report on Civil Society and Policymaking in India: In Search of Democratic Spaces. It is a dynamic stream of gathering inputs from the labyrinths of the government machinery and interested private actors, to suit evolving grassroots needs.

Without advocacy, the chasm between the needs perceived by the government and nonprofits and the ground realities of the stakeholders will widen, rendering policies inadequate in their outcomes and stagnant in their purpose. By closing the feedback loop between stakeholders, advocacy efforts push policy design to be more reflective, contextual and have built-in accountability structures.

For example, now in its 16th year since institution, the Right to Information Act 2005 (RTI) is a glittering milestone in the growth of public advocacy as a channel for development work. A result of years of campaigning and action from individuals and organisations in itself, the Act is an excellent case study on the success of advocacy—on how mobilising diverse voices and deliberate actions can influence public policies. And in turn, RTI has galvanised public action further, bridging the gaps between government processes, citizenhood, and grassroots activism.

Public advocacy has not, however, been without global skepticism.

There is always the concern of “the mischief of factions,” as famously noted by James Madison in the context of the USA. Be it in India or otherwise, fears abound that public advocacy places undue focus on singular issues without a holistic lens, or that those with influence skew public policy towards their own interests.

However, in viewing the government as a sum of the individuals working within it—and not as a faceless monolith—one could argue that the dangers of skewed perspectives and misplaced policy are higher without the layer of public scrutiny and action than with it.

For example, an important formal structure of advocacy is to participate in legislative processes by responding to calls for public inputs on impending policies. This was done after the Draft National Education Policy (NEP) 2019 was released, wherein public feedback was gathered by the Ministry of Education. One of the numerous changes between the Draft NEP 2019, and the final NEP 2020 document, included the scrapping of the provision for private Boards Of Assessments (BOAs). Most recently, the Justice A.K. Rajan committee invited public inputs on the impact of NEET-based medical college admissions in Tamil Nadu, in response to strong public debate on the exam in the state.

Civil society actors within the education sector in India have additionally paved the way for informal advocacy by instituting structured channels for discussing and influencing policy design. The Nexus of Good Foundation is one such example: it identifies success stories from the field and facilitates the growth of peer networks. There’s also the Right to Education (RTE) Forum that was formed as “a collective national initiative of the civil society” to monitor the implementation of the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education (RTE) Act, 2009. Collaborative peer spaces such as these, which can be easily supported by ordinary citizens too, nurture the potential of advocacy interventions to catalyse education reform. The RTE Forum, for instance, conducted a National Consultation on Draft Education Policy 2019 after its release in collaboration with Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability (CBGA). The consultation sought to build a critical discussion on the fiscal implications of the Draft NEP in relation to school education, leading to greater public engagement in the evolution of the final document.

On the occasion of International Day of Education & National Girl Child Day, RTE Forum is releasing a Policy Brief on #GirlsEducation

Date: 22nd January 2021, Friday

Time: 11 am to 1 pm.Link: https://t.co/ImS1IIhYGX…

Meeting ID: 846 5011 2935

Passcode: 947171 pic.twitter.com/8AVeZjT1zn— RTE Forum (@RTEForum_India) January 20, 2021

Judicial modes of engaging in advocacy—such as through PILs—also democratise access to justice for every citizen, and have seen immense success, such as in the case of Vishakha Vs. State of Rajasthan. This PIL, filed in the background of caste-based sexual violence, formed the basis for the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act 2013. The Act mandates the formation of internal complaints committees within educational institutions, so that all stakeholders within them can seek redressal in the case of sexual harassment.

So, What Kind of Advocacy For Better Education Works Best?

How non-profits choose to address India’s educational issues, and how they advocate to solve them, differs. Many organisations opt to create a deeper impact instead of scaling their interventions to larger groups of students. This creates pockets of excellence where best practices are adopted at a meagre scale.

However, education is a multifaceted field of action: layers of actors work in parallel towards improved learning outcomes for a large and dynamic group of young beneficiaries. So, to create in-depth interventions aimed at achieving quality public education at scale, it is invariable to address all levers of the education system simultaneously. Madhi’s journey and experiences indicate that for problems that demand urgent redressal, it is critical to identify solutions that suit scale, in order to avoid compounding crises due to delayed action.

Given the government’s well-oiled machinery and extensive reach across India’s expansive and diverse demography, partnering with it is the most efficient way for nonprofits to deliver interventions at scale. It is important for organisations to make the conscious choice to influence policy discourse from the nascent pilot stages. As the Former Secretary of School Education, Mr. Anil Swarup, quipped at Madhi’s recent conclave on building government partnerships, a “nexus of good can happen when the public and private come together”. In the context of the widening gaps in access to education as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic such partnerships for immediate and large-scale action become much more relevant to collectively emerge from the crisis.

How Do We Impactfully Advocate For Education?

“I do not think very highly of NGOs and am always suspicious of their intentions. They all come with their own agenda—to show the government in poor light and to tell us they know better.”

This was something a government official told Madhi during our first meeting with them at the beginning of our government partnership journey in early 2017. A year of meaningful communication and project implementation later, we had the privilege of learning that the same official’s belief had changed. They now “trust that Madhi will recommend only the most relevant approach [for education reform].”

Over the years of building a long-term partnership with the Government of Tamil Nadu, we have learned from our missteps and identified three key insights on nurturing ‘successful’ government relations while scaling education reforms.

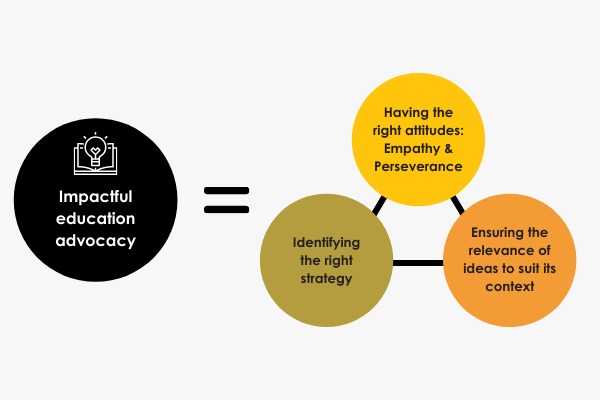

- Identifying the right strategy

Pooja Kulkarni, Special Secretary to the Tamil Nadu Government’s Finance Department, points out that complementarity is the underlying theme of any partnership with the state. That is, the private partner’s project implementation should aim to improve the government’s pre-existing resource capacity.

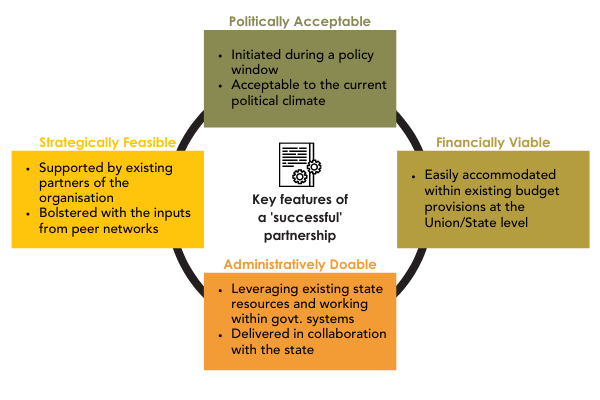

Identifying a gap where the private actor and the government can work together, and nailing down the nuances of the partnership—such as funding sources, division of responsibilities and accountability structures in no unclear terms—are key to beginning such a partnership. Drawing from the seven-part rubric to evaluate a successful Public Private Partnership (PPP) strategy by Anil Swarup in his book ‘Ethical Dilemmas of a Civil Servant’, the following framework can aid organisations in evaluating the right partnership strategy while approaching the government.

- Having the right attitudes

Empathy and perseverance. Not a single day goes by for those engaged in government relations where these attitudes are not called for in spades. Understanding that it is indeed a partnership towards an aligned goal, is key to sustained advocacy efforts.

For example, while the credibility of advocacy practitioners depends on their grasp on grassroots realities and their proven expertise, neither can act as a substitute for the knowledge of intricate bureaucratic details that government officials possess. As Vikas Garad, Deputy Director, of SCERT Maharashtra explains, “nonprofits are only in the system to help out the government. Everyone within the system must feel the same [level of trust and respect]. This will help the projects’ long term sustainability, and in building the state’s trust for the organisation.”

Dedicating focused attention and resources towards the softer aspects of building government partnerships is therefore important for organisations. This ensures that adequate processes and internal monitoring systems are in place to drive advocacy on a regular basis.

- Ensuring relevance

A prerequisite for effective partnerships, and in turn advocacy, is the relevance of the ideas shared to the respective socio-political context of the project, to the work by and learnings of other government partners, and to the timing of the conversation within policy design stages. In other words, advocacy needs to be within a conducive policy environment that will “help make the whole greater than the sum of the parts, through judicious use of policy instruments,” and needs to be presented at the right stage in the policy design process.

To that end, we must ensure that all recommendations are derived from the bottom-up, to fit the specific needs of both the beneficiaries and other actors. Collaborating with other organisations and individuals to hone policy recommendations, and learning from ongoing work by others in the field, can go a long way in ensuring that government partnerships yield the most effective solutions for its beneficiaries.

Moving Ahead

“Once the question was ‘How can development agencies reach the poor majority?’, now it is ‘How can the poor majority reach the makers of public policy?’” [1]

The bane of policy design and execution in large countries like India is that unique contexts are not easily catered to. Without that critical piece of the puzzle, there is great transmission loss from paper to project implementation, always at the cost of the end beneficiary. Advocacy is integral to bringing context to the planning table and facilitates the birth of innovative solutions at multiple implementation stages such as through launching blended teacher training processes, creating customised data dashboards for governance, and more.

Even as we emphasise the need for customised policy design, we cannot forget the guiding principle behind engaging in state partnerships—the pursuit of scale at depth. As a result of the COVID-19 related school closures over 28.6 crore children from pre-primary to secondary levels, have been affected across India [2]—the sheer breadth of the crisis demands at-scale solutions.

Of course at-scale, contextual policies across the many complex segments within the education system translate to revolutionary impact only when they are effectively implemented in an integrated manner—the ethos of which inspired us to write this series of articles on the ‘Five Tenets of Education Reform’. The interlocked issues of the education system cannot be addressed in silos. We hope that through sharing our insights on unravelling the elements of holistic education reform, we can collectively take a step forward in creating sustainable transformation in learning opportunities for every child.

For more on how to reform India’s education system, curated by The Bastion and the Madhi Foundation under ‘The Five Tenets of Education Reform’, click here.

[1] Bratton, M. (1990). “NGOs in Africa: Can They Influence Public Policy?”, Development and Change, (21).

[2] UNICEF The Remote Learning Reachability report, Aug 2020.

Featured image: a demonstration on educating the girl child, held on Women’s Day (the 8th of March this year, supported by the Right to Education Forum. | Courtesy of RTE Forum via Twitter.