The new National Education Policy (NEP) is fresh off the press, and contains big plans for school education. In light of India’s all too famous marks-oriented education system, the NEP seeks to make learning in school holistic, and encourages young minds to be curious, creative, and critical. However, it remains to be seen whether our curriculum as it stands can actually achieve this-what are the exact learning tools we need to deploy to bring about this change?

Enter Katha, an NGO founded in 1988 by Geeta Dharmarajan (GD). Katha, through its variety of reading and publishing initiatives in children’s literature, “brings children living in poverty into reading and quality education.” Its multiple initiatives over the years range from children authoring their own books and stories, to setting up community libraries in underprivileged areas, to Katha publishing over 400 titles for children in different languages. Its award-winning education model currently benefits over 160,000 underserved children and 1,100 teachers annually.

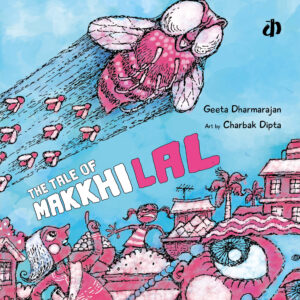

Katha’s focus on creating steady reading habits have helped over one million children develop a holistic understanding of the world around them, while also providing many with the confidence to creatively think about and narrate their own stories too. In light of Dharmarajan’s latest title for children The Tale of Makkhilal-which tells the story of why a community curiously worships a troublesome giant fly-Aarathi Ganesan (AG) sits down with her to discuss the learning potential trapped within children’s literature.

As the NEP seeks to revolutionise children’s learning in India, Dharmarajan sheds light on the pedagogical innovations we first need to make to make learning valuable for children: reading and writing more children’s literature is a great place to start.

AG: What I find interesting about children’s literature is that it is often not considered ‘serious’ literature in India, simply because it tells a ‘simple story’ to children. Would you agree?

GD: I completely agree! Given everything we have all learned from our different oral traditions, it’s rather surprising, if not sad, that we don’t think the story is very important in India.

After all, out of the 6,600 linguistic cultures that the world is home to, almost all of them use the story as a base for learning and transmitting culture-the same is true for our many cultures too. Noam Chomsky famously said that “grammar is the building block of every language,” however, I would counter that by saying that stories are the building blocks of every language! It is stories that evoke emotions and connections, and anchor us in our lives.

That value of a story, which is inherent in children’s literature, isn’t recognised as much. When parents look at a children’s book, it’s not something they always want to give to a child. As parents, we instead look at books that will be edifying for the child, which will make her do ‘well’ in the future. Right from the time a child is born, we often burden them with our own lost hopes and dreams. We don’t give importance to what the child wants vis-a-vis what the child needs. Our children end up buried under stereotypes and pressures, while the value of the storybook gets drowned in all of this noise.

Yet, that doesn’t mean stories aren’t powerful, especially when they are developed and explored by children. The power of stories is simply amazing!

AG: Could you describe how children’s literature developed by children can be a powerful learning tool for them?

GD: When children are encouraged to write their own stories, not only is their imagination doubled and trebled–a much needed 21st-century skill–but the power of writing their own stories and poems gives them a sense of ownership; this helps a child reclaim their own voice. It also helps them move along the trajectory of self-developed knowledge. How? Because our stories make us think, ask questions, and develop them further. As this happens, we question and think through multiple Big Ideas constantly.

That’s why Katha believes that learning through stories is important. It is this principle that defines our ASBL, or Active Story-Based Learning model. This model constitutes the classroom practices module of the ‘Story Pedagogy’ that I developed for Katha, which is now being used in government schools too. Story-based learning, at the heart of it, is about learning through asking questions. When a child learns to ask questions, her curiosity is awakened, and thus so are her critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

For example, when we first started our work in 1990 in New Delhi’s Govindpuri, our “deschool” had just five children enrolled in it, and two teachers, Savita (who is still with us) and Anita.

When we asked the children to tell us a story, they said they couldn’t tell us one because they didn’t know one. So, we asked them to go home and ask their parents to tell them stories, and to come back the next day. One child began narrating their story, then after that another, and then another. We recorded all their stories. The teachers would write down the story, and then the child would illustrate it. We’d then add each such ‘book’ by the child to the school library. Slowly, illustrated storybooks written by the children, who did indeed know stories and how to tell them, filled up the library!

This ethos continues in our work, especially in our new initiative SherNama, which is a creative story writing project that aims to platform stories of, by, and from children living in the margins. The name is inspired by the Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe, who once quoted the proverb, “until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.” Children must be their own historians. I don’t want someone to come in with a middle-class perspective and write for them about ‘maximum city’, which is what we usually do, even for adults. Children know what they’re going through, and when they write and articulate their thoughts on their own, adults can learn much from them, by understanding what the child is going through.

AG: The majority of our children’s literature is rarely written by children themselves, though-it’s written by adults who may often inject their own moralities or instructive ideas into a narrative for a child. Do you think the distance between a child and an adult’s perspective affects the ability of children’s literature to be a powerful learning tool?

GD: Children like to be taken seriously-they are always yearning for attention. By writing for them, an adult recognises the child and their experiences, which is why children’s literature written by adults is also important. We shouldn’t underestimate the amount of effort it takes to write children’s literature either. Every great writer, whether it was Rabindranath Tagore, Mahadevi Varma, Mahasweta Devi, Sukumar Rai, or MT Vasudevan Nair, they all also had the ability to write for children, which is much easier said than done.

After all, what is a story? It’s a big idea! We then colour in that idea with dialogue, characters, and images to make it understandable for children. But, to communicate that idea effectively to a child, to make them think, you really need to be a consummate artist. Most of us think if we can string words together in English, Tamil, or Hindi, that we can write for children. But, that’s simply not enough.

AG: One’s childhood is inherently shaped by social indicators, or dividers, of caste, class, gender, religion, and regional identity. Seeing as students can learn through stories and children’s literature, how can they help young learners learn about themselves, and the fragmentation they see both within and around them?

GD: I believe that all children are born with self-esteem, confidence, curiosity, and an ability to innovate. Children are always striving to understand the world they live in.

It is adults, who heap their insecurities and biases on children; they make them feel like they’re not good enough, or that they’re ‘different’. I’ve been working with young children in Tamil Nadu and Delhi since 1977, and whenever I’ve walked into a primary classroom, I have never ever felt a sense of any divisive thinking within the students themselves. Those divisions-whether social, cultural, or gender-based-are foisted on children from the top, be it by the media, politicians, parents, grandparents, or society at large.

For example, in Tamil, we have a saying “naalu peru yenna soluva?” which translates to, “what will those four people say?” It’s a saying used to prevent people, especially children, from straying from societal norms. When I was growing up, I heard it all the time. We were always scared of these unknown ‘four people’ because they could and would say something bad about us in public if we didn’t behave ‘appropriately’, especially as we were girls. Who we became finally depended on whether we abided by their norms or not.

So, social divisions are clearly pervasive; we need to build a non-divisive nation on our own to overcome them. But the question is, how do we do it? Can children’s literature, or literature for children, make that happen?

I think it can, but that desire to make children’s literature effective comes from the parents again, and as you said, most don’t consider the act of reading stories to be serious business. However, there is a small but growing minority of young parents who encourage children to read widely. They want their children to discuss big ideas, to be compassionate and kind, to overcome a divisive world. These could be the parents of first-generation learners, who see their children growing and becoming more empowered through reading and literacy. They can also consist of educated families, who have recognised the power of reading and literature to break stereotypes over generations, and push their children to read more so they can be truly free, fair, and fearless!

The success of children’s literature as a learning tool also depends on whether our educators at large see stories as capable of imparting long-term knowledge to children. For example, the last few lines of Makkhilal state, “be careful who you choose your God or King to be.” This is a light-hearted story about this giant, scary Makkhi flying around; people are afraid of his powers, so they worship him. But, that last question, in the context of this ‘simple’ story, is an extremely political one, that could stay with children for a long time. And if it does, perhaps they will continue wondering down the line, when they’re much older, about whether choosing to subscribe to an inherited God or King who doesn’t align with their thinking is the right thing to do. That is the educating power of a story, as we look to overcome divisions and monoculturalism.

But, is any of this self-reflection encouraged by the NCERT, or ICSE? We constantly define education in terms of ‘information’ alone. But, why is understanding Big Ideas on one’s own terms being left out of our curricula? When children think through ideas that they mature, decide what’s right or wrong for themselves, and develop a sense of the self. And perhaps, it’s only when they think for themselves based on their own wisdom, that these social divisions can be overcome too.

AG: When you go to bookshops, you generally see much more children’s literature written in English, rather than regional languages. Why do you think that is? Does that mean English is dominating this market, and limiting children’s publishing to specific languages? What more can be done for the larger population of children looking to read in regional languages?

GD: I disagree, English definitely isn’t dominating! In fact, if you visit the World Book Fair at Delhi, which is one of the biggest in the country, you’ll find that there are more regional language publishers catering to children, than there are in English. The quality may be different from English language publishers, especially given that the latter print on high-quality art paper, and sell their books at Rs. 100 or 200. But that’s also because they’re catering to a different audience.

The problem you’re addressing though, is one of visibility-and that often comes down to the distribution of book stocks across bookstores who don’t accept bhasha (regional language) books.

For example, when it comes to Katha, we publish Hindi and English translations of good original poems and stories from the bhasha. We find gems from India’s 2,500 year-old literary history across languages. But, given that global publishers now dominate India’s bookshops, all of us fiercely independent Indian publishers have been unable to stock our books in the shops. Marketing has become more difficult and more expensive for the likes of smaller publishing houses. In our case, our books are stocked in libraries across India, instead. So, situations like these can definitely affect the visibility of regional language publishing.

Regardless of this situation though, bhasha publishers should ensure that they continue to provide children with the best of children’s literature. The ‘best’ can be defined both in terms of externals-like paper or printing quality-or the content itself. What the content should be is important to examine, because the spaces for children’s identities within regional language publishing are sometimes limited. Restricted thinking abounds. You can either be a ‘good’ or a ‘bad’ child. There are no grey areas in between, often because the author’s inherited morality filters into the narrative.

But then, on the other hand, you also have the likes of M.T. Vasudevan Nair writing in Malayalam, or Gijubhai Badheka writing in Gujarati, or Paavanan writing in Tamil for Katha, and their stories for children are delightful and incredibly complex. We just have to strive more to push these voices forward as much as possible. We definitely shouldn’t simply translate English stories into regional languages to fill a gap.

Why? Because English children’s literature often looks at a manicured front lawn. It is trying to please the child who speaks English and perhaps also seeks to engage with other foreign children’s literature. That also explains why we have so many Enid Blyton and Harry Potter clones in the Indian market. Ultimately, we need to explore the ‘backyard’ of our own stories and culture too. Our writers and publishers need to courageously cater to India’s 300 million-plus children, without thinking too much about foreign audiences or awards. We have the freedom to write and publish what we want, so let’s be fearless and fair publishers for children!

Featured image courtesy of Katha. | Views expressed are personal.

Beautiful interview. Children’s literature in English is like a manicured front lawn. Loved that expression. And wonderful to learn about the regional authors. Will definitely check out their work. Great work Geetha Dharmarajan!! And connect with so many of your thoughts.