Having lived in Kashmir as an educator, but not as a learner, Mubeen Masudi brings to the table a unique perspective on education. Although born in Kashmir, his father’s transferable job meant he grew up across the country and studied in Tier-1 cities. Mubeen is very conscious of the distinct privilege he enjoyed over his peers who were educated in Kashmir, over even those who had the same economic background and talent as him. In 2007, he became the first Kashmiri Muslim to make it to IIT Bombay–the first in 49 years. He returned to Srinagar in 2012, with an aim to improve the quality of education in Kashmir, and has lived and facilitated learning through many lockdowns since. This provided Mubeen with first-hand experience of how difficult it is to facilitate learning under a lockdown, far before the pandemic stalled education system. Incidentally, the second student to make it to IIT Bombay after him in 2016, was from his own organisation RiSE Institute.

“When I first returned to Kashmir I wanted to provide students with the right kind of support and guidance to pursue their ambitions, and to bridge the gap between talent and opportunity. But these lockdowns made me realize that learning requires way more than that. As long as conflict persists, the educational opportunities that the rest of the country have and that Kashmiris have can never be equalized. If the rest of the country studies for one year, Kashmiri students effectively study for an average of 6-7 months,” says Mubeen.

Of Aspiration and Achievement

The uncertainty of life in a conflict zone proves to be the biggest hurdle Kashmiri students face. According to Mubeen, “The biggest challenge is that they can never plan for themselves. They are used to having short-term annual goals, where the priority is simply to get promoted to the next year. They can never anticipate what the situation in Kashmir will be like even in the next six months. If there is a major lockdown, preparation for competitive exams goes for a toss.”

RiSE works across a large range of educational aspects, but primarily focuses on facilitating entry into higher education institutions. Working primarily with students from Grades 10-12, they have conducted talent search examinations, organized counselling and coaching for competitive exams, and assisted with college applications. Since 2012, they have seen a tangible increase in the number of students admitted to institutions in Kashmir, other parts of the country, and abroad.

“We’ve been able to expose students to more opportunities, which has cultivated greater interest [in education]. In 2018, one of our students, Adeeba Tak, made it to the University of Pennsylvania on a 100% scholarship to study Mechanical Engineering. For a girl from South Kashmir to achieve this is an unprecedented result. Stories like this create relatable role models and since then, we’ve had many more students approaching us for US college applications, with more students securing admission in top American colleges,” says Mubeen.

What about the school system that prepares students for entry into higher education institutions? Mubeen maintains that the school system is in a terrible state, and observes that it gets progressively worse in higher secondary grades. It is a challenge for a conflict zone to attract the best talent, in the form of competent teachers. Decades of conflict have only compounded this state of affairs, making poor education a generational problem.

For those of us outside Kashmir, grappling with the challenges of a lockdown for the first time, Mubeen draws an analogy. “For a student in Grade 10 in Delhi, they’ve lost a few months. The priority [there] is simply to complete the syllabus and get done with the exam. That student will not focus on olympiads or extracurricular activities, but just on the bare minimum to help them get through this exam. The priority of parents, schools, and the government, would also be the same. This is what the constant reality looks like for students in Kashmir–where the only priority is being promoted to the next class. Everything else is a luxury because you never know how many months you will get in an academic year”.

With the syllabus barely, if not rarely completed, and many students left to study by themselves, co-curricular and extra-curricular activities are a distant dream.

This academic year, schools in Kashmir have been closed since August, and just opened for 2 weeks in February–but this cycle repeats year after year. “Most competitive exams are supposed to be equal entry points into higher education institutions. Everyone is equal on paper and must take the same exam, yet you have someone from Delhi with 12 years of education, competing with someone from Kashmir with effectively 6 years of education. I’m 100% sure that if my father didn’t have a transferable job, and I had studied in Kashmir, I would never have made it to IIT Bombay or any good engineering college for that matter. I got incredibly lucky,” adds Mubeen.

Schools open in #Kashmir after winter vacations. Never seen children smiling while on way to the school. Don’t think one can photoshop such lovely pictures. pic.twitter.com/QVv0642pEY

— Aditya Raj Kaul (@AdityaRajKaul) February 24, 2020

Sheikh Faraz, one of Mubeen’s students at RiSE, gave his 12th board exams in the midst of the lockdown in November 2019. With the internet shutdown last year largely hindering his application to top-tier US colleges, he is now remotely preparing to give the JEE entrance in July. How has the JEE preparation been going amidst the lockdown? “August was a crucial time for those of us answering the JEE exam this year,” explains Sheikh. “We were 18 months into the preparation and were in a good mindset. The shutdown created this psychological block, and we were really unable to find the motivation to study for months. We’re now trying to get back on track and bridge the gap but it’s difficult to get back into rhythm when everything ahead looks uncertain–every two weeks they still take away our 2G for two or three days.”

The Challenges of Identity

Having worked with many government schools across Kashmir, Mubeen remarks that he hasn’t observed much of a gendered gap in access to education. In fact, girls’ schools are better equipped in terms of infrastructure and faculty and see a higher number of students and attendance rates. “Kashmir is equitable in that sense. J&K is the only state in the country whose medical college has 50% reservation for girls–over the past 10-15 years, 50% of the doctors graduating have been women, which has only encouraged more women to apply,” he says.

The challenge, however, has been negotiating with many parents who are apprehensive about sending their daughters outside of Kashmir to pursue higher studies. With the increasing visibility of right-wing politics across the country, Mubeen observes this hesitation when it comes to sending sons as well.

“From what I hear from my students, they’re very comfortable with the shift to foreign universities, whether in the US or UK–for the first time, they feel truly free and cannot be questioned for what they think, and don’t have to fear action being taken against them. But in India, they face the double whammy of being Kashmiri and then being Muslim,” Mubeen explains. “Nearly 96% of Kashmiri residents are Muslims. In general, it’s extremely challenging being a Muslim in India–it has always been difficult, but the past five years have been particularly bad. To add to that, the layer of Kashmiri identity makes things harder. For instance last August, Kashmiri students had to watch people around them celebrate what was being done to them, which naturally made them very angry. In Kashmir, you are taught that whenever outside Kashmir, one shouldn’t respond irrespective of the provocation. You always live in fear of being attacked if you speak your mind–and that does happen.”

Safoora Zargar’s Detention Against International Law Standards to which India is a state party: American Bar Association Appeals For Her Immediate Release#ReleaseSafooraZargar and all other students and anti-CAA activists. https://t.co/sKVqJMbF5k

— Umar Khalid (@UmarKhalidJNU) June 13, 2020

With the demographics of Jammu and Kashmir largely shaped by conflict, evident through the dominance of Muslims in the Valley and Hindus in Jammu, the reality is that the youth of different religious groups within Kashmir themselves may experience conflict and education in painfully different ways.

J*, a Grade 12 student at RiSE, has decided to apply to study abroad. She shares that the political situation has solidified her resolve, seeing the environment post the abrogation of Article 370, and the manner in which Muslims and Kashmiri Muslims were targeted during the anti-CAA protests. “We’re apprehensive about studying in India, as Kashmiris,” says Sheikh Faraz, who is giving the JEE exam next month. “I’ve always thought Delhi was a calm and tolerant space, but when my cousin joined a private university there last year, he was severely teased and abused after the abrogation of Article 370. He had a really tough time, especially given it was his second month away from home. If our marks are good enough, our teachers have advised that we go down south. They tell us it is relatively safer there.”

The Internet Variable

RiSE used to organise live online classes for a few schools, but decided to do away with them in 2015 when internet stability started becoming uncertain. Instead, remote classes were organized by recording lectures and sending them on a Pendrive to various schools. When asked about how education in Kashmir has adapted to the challenges of lockdowns, Mubeen says that in the absence of internet connectivity, local entrepreneurs and educators have not had the opportunity to innovate local ed-tech solutions.

How schools get in touch with students and teachers, through ads in local newspapers. People not sending children to schools. #kashmir pic.twitter.com/p6BEqhPhaQ

— vijaita singh (@vijaita) September 21, 2019

The Internet has the potential to be an equaliser as most existing ed-tech companies have started offering their online courses for free–but, all of this is possible provided you have a smartphone and a 4G connection. However, access in Kashmir is a big question with low 2G bandwidth, and intervals of complete Internet shutdowns too. Broadband WiFi is not accessible to a large section of students, forcing them to rely on mobile Internet connections. With India holding the record of the “longest ever Internet shutdown in a democracy” thanks to its actions in Kashmir, this raises questions about the viability of online learning in the Valley.

We asked two Indian students—one in #Kashmir and the other in Tamil Nadu—under lockdown to record their screens as they download the same reading assignment.

This is what it looks like.https://t.co/pB86oU5CIR pic.twitter.com/k2OOj2gUub

— Anup Kaphle (@AnupKaphle) May 19, 2020

Mubeen narrates the difference in approaches to education during a lockdown 2016 and 2019, which reveals how internet connectivity factors into learning under a lockdown.

In 2016, following the death of Burhan Wani, while there was a complete curfew across the state, landlines were working which enabled teachers to stay in touch with students. Broadband connections were also working, which allowed Mubeen and his team to download video lectures and transfer them to nearly 400 Pendrives which were distributed to students. Mubeen would ask students to come early in the morning, before the CRPF began enforcing curfew, to collect these Pendrives. Once the situation began improving, they began organising classes and counselling sessions at 5:00 AM, which would wrap up by 7:30 AM (after which restrictions would be tightened, making it unsafe to travel). Access to phones and the Internet helped students stay in touch with their teachers and access learning material.

2019, however, was unlike anything even Kashmir had ever seen, with a complete communication blackout for three months–this time around, there were no landlines, broadband connections, or mobile Internet connections. Everyone, including students, was simply on their own. After two to three months, once landline connections were restored, the RiSE team began getting in touch with students, and actually flew to Delhi to download lecture content and prepare the Pendrives. In November, they began distributing these Pendrives, and gradually restarted their classes and counselling sessions, with the same 5 AM to 7:30 AM routine. While things began to normalise in February, lockdown returned to Kashmir again in light of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since the COVID-19 lockdown, RiSE has started free classes for Grade 10 and 12 students on Zoom, which can be sustained on 2G internet connections. These were makeshift classes, says Mubeen, but better than nothing.

The Question of Online Examinations from Kashmir

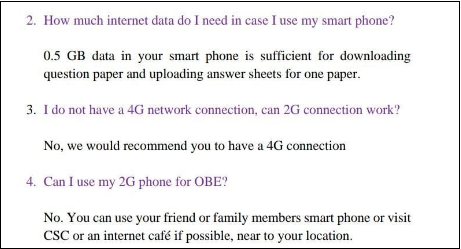

In the meanwhile, Delhi University has decided to go forward with its remote Open Book Examination, despite this move being widely contested on grounds of inaccessibility. To write an exam online, one requires a smartphone and a 4G internet connection–accessing the latter being an issue for many students in Kashmir particularly.

Nousheen, a final year Kashmiri undergraduate student, is anxious about how she will do this over a 2G connection. “Most of us don’t have broadband connections, especially in rural areas. Even for those who can afford it, it’s difficult to install them now with all the offices shut. The university guidelines talk about Common Service Centres for those without 4G connections but nobody seems to know where these are in Kashmir, how functional they are, and how accessible they will be with the lockdown. Attending classes is hard enough, I had to travel to a relative’s home to use their WiFi just to download the Zoom app. When professors send audio recordings and readings, I leave them overnight to download. The situation is so unpredictable in Kashmir, what if there is an Internet shutdown during the exams and even the 2G is taken away? What if my locality becomes a red zone, how will I travel anywhere else to give these exams either?”

Nousheen shares that the Internet restrictions hinder her preparation for entrance exams too. It’s difficult for Kashmiri students to find out when forms open and fill them out on time, which results in many students missing deadlines. M.Phil and Ph.D. students at JNU have been conducting online coaching for the JNU entrance exams over Facebook Live, and have also created a Google Drive of resource materials, but she still can’t access or make use of either. Uncertain about whether entrance exams might switch to an online mode, Nousheen is considering returning back to Delhi now just for a stable internet connection, but still worries about finding accommodation amidst the COVID scare.

“As Kashmiris we’ve always dealt with the uncertainty and resource crunch, I gave my 12th board exams during the 2016 turmoil. However earlier, as Kashmiri students, we competed amongst ourselves–Internet restrictions and curfews impacted everybody. Now that we’ve gone outside to study, it’s much more unfair. We’re at a disadvantageous position competing with so many people who have access to the Internet, and that is an added burden,” adds Nousheen.

Accommodating the Challenges of a Conflict Zone

Maknoon Wani, a final year student at the Delhi School of Journalism, recently wrote about how the admission process to a private Liberal Arts university failed to take into account the economic loss his family faced during the lockdown, or provide him with the requisite financial aid. It was revealing of the larger absence of mechanisms to accommodate students from conflict zones within educational institutions, and the need for alternative metrics to evaluate such students when it comes to matters of financial aid and fee concessions.

“I was accepted into the program in April, and in the process of applying for financial aid, I had to show my family’s Income Tax Returns over the past three years,” Maknoon explains. “They looked at our financial health for the last three years without considering the lockdown, and especially the last eight months, where my family incurred huge losses. Their policy for evaluating students from conflict zones is vague and ambiguous, I don’t know how they select and grant aid. I just wanted to make a point that you can’t treat me the same as a student from mainland India–my needs and difficulties are different.”

Now applying to other institutions, Maknoon factors in the Internet restrictions into the challenges he faces. “It’s difficult with the Internet limitations–it took me four hours just to fill up the JNU application form on 2G. I now have access to broadband WiFi, which took nearly a month to install. Only major towns have the fibre cable laid down, rural areas do not, so students there will not be able to install it even if they could afford it.

The Public-Private Gap & Learning Beyond

Kashmir witnesses a wide gap between public and private schools, with the restrictions on the Internet, only further widening that gap. J*, who studies at a private school in Kashmir, shares that they were given hard drives with notes after the shutdown last year, but were left to make sense of the notes themselves, which was difficult without the Internet to fall back on. Now, because of the 2G restrictions, their online classes on Zoom are restricted to audio interactions, with teachers unable to make use of cameras or the blackboard function, affecting comprehension.

“Most Kashmiris have already cultivated the habit of doing things on their own, of being self-sufficient,” says J*. “Last year forced us to completely rely on ourselves; but it wasn’t just last year, we’ve seen lockdowns all through our childhood. We’re used to self-studying but online classes are new to us as well, and it’s taking us a much longer time to adjust with 2G internet. We don’t know what to expect, but I just hope we will be able to give our exams in peace this year.” However, she is aware that this is still more than what her counterparts in public schools have access to.

“I always liked the unknown. Ironically I familiarized myself with the uncertainty of life. Life can change in any minute of the day. God can turn anything around in a speck of a moment. I know for a fact that everything changes. Nothing stays the same. This too shall pass.”

— RiSE (@RiseWithRiSE) May 28, 2020

A*, who completed her Grade 12 at a public school in Kashmir in November last year, says students were left to fend for themselves even when it came to their board exams. She speaks of the harrowing psychological effect of living and learning in a conflict zone, “For two months after the lockdown, I was just very numb and didn’t know what to do with myself. The area I live in is very volatile. There would be army raids and arrests every second day, for months I didn’t step out of my house. When I did, the landscape had changed, there wasn’t a single house with the windows intact. They were arresting young people, even 14-year-olds–the environment was so unsettling.”

She shares that public schools are largely in shambles and students are often left to fend for themselves, particularly during lockdowns. Before the August 5th lockdown, she largely relied on the Internet to learn and explore, but then even that was taken away from her. “We’ve been in a space of intellectual stagnation since 2016,” she shares ”and I have no idea how to go forward now. My parents don’t want me to get out of Kashmir, they fear for my safety. But at least in Delhi, I will have the Internet.”

*Names changed | Featured image by Faisal Khan, reproduced with permission.

[…] Learning Under Lockdown: Voices From Kashmir, by Evita Rodrigues […]

Hi there friends, itss wonderful paragraph regarding tutoringand fully defined,

keep it up all the time.

[…] Note *Names changed.. Note –Thanks Evita for sharing this! –This article first appeared in https://thebastion.co.in/covid-19/learning-under-lockdown-voices-from-kashmir/ –All photographs courtesy Mubeen Masudi Evita Rodrigues is an undergraduate student in […]

I did not realise that school and college students had such a series of obstacles which substantially handicaps them when faced with competition for higher education or jobs against students in the rest of India.

I wish I could help any student who would like to study in Goa — our standards in school/colleges may

be lower than schools/universities in Bombay, Madras and Calcutta.

I would gladly help them in their studies.

Thanks for covering this issue. Lucid writing.

Thanks for covering this issue at this depth. The writing was lucid and easy to understand.