Imagine this scenario: a prominent influencer shares a horrific story on Instagram, of a couple who had tortured their pet dog, injuring it gravely and possibly physically disabling him for life. The irked influencer in question puts up a story with a picture of the couple, their full-names and phone numbers, along with a message to their followers: “Go tell them what you think about their behaviour.”

While most would argue that the couple had it coming—given that animal cruelty is a crime not to mention a punishable offence—the influencer’s actions unfurl another legal conundrum: they essentially reveal the personal information of two people without their consent on the Internet, with the intention of causing harm.

What in this case could be termed as a ‘righteous’ move could turntable, as often happens on the Internet. Consider the case of Rohan Joshi, a well-known Indian stand-up comedian, who received extreme abuse after his phone number and home address were leaked online by those offended by his jokes.

This process of literally dropping documents is called doxxing (or doxing)—accounts state that it originated in cyber-vigilantism, with one of the earliest incidents being when white-supremacists were doxxed on Usenet. However, while the need for accountability and social-justice is important, what that influencer is initially asking for (and the very notion public shaming exists for) is a mob-trial. One that exists to harass, defame, and otherwise put an individual in distress.

The important aspect of this trial is intention—is it only if your intentions are truly ‘bad’, that you deserve to be abused by strangers online? Who decides if your intentions are bad in the first place? What happens when you are targeted for being different, or for being from a marginalised group, or are standing up against a large army of sponsored internet trolls committed to spreading disinformation?

The bottom line is that the terms of engagement in doxxing are subjective and unpredictable—which means anyone can be doxxed for anything. Despite all the fallacies surrounding protectionism versus rooting out the problem—this issue is not going away anytime soon. In a way that is oddly reminiscent of the pepper spray I carry if I’m out late, as a user of the Internet, you have to protect yourself too, the best you can.

But, is doxxing really that big an issue in a country where we do not have that much digital access in the first place?

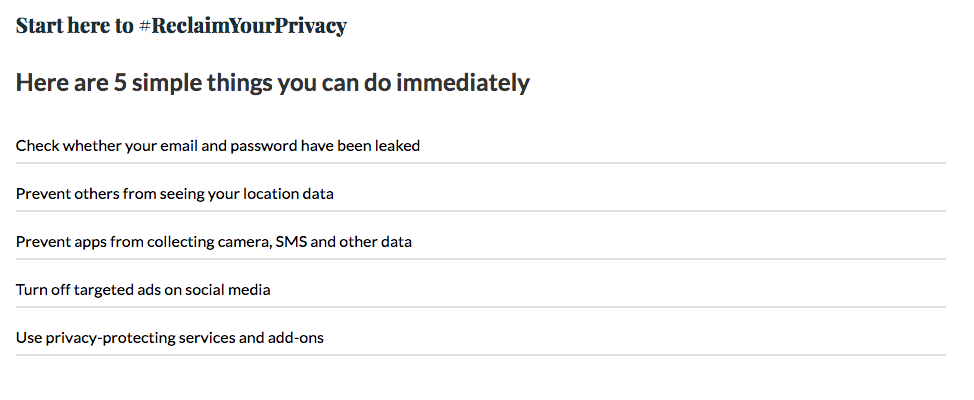

The prevalence of doxxing in India is much more than meets the untrained eye—and often gets lost under the wider category of cyberbullying. To address this, the Aapti Institute runs the online awareness platform ‘Reclaim Your Privacy (RYP)’ a collaborative initiative supported by Omidyar Network India, conceptualized by the 21N78E, and backed by Aapti Institute’s research. RYP’s main objective is to raise awareness about issues of cybersecurity which are generally siloed within the professional reaches of tech policy. Their campaign, situated in the social media sphere to spread awareness and offer better practices for safer digital habits, is premised on the fact that no one would be prepared to radically shift their practices of online safety in a day. The cases of doxxing Aapti has encountered are revealing—as is generally the case online, it is vulnerable, marginal groups that are mostly attacked.

“When it comes to children,” says a representative at Aapti, “Indian children are the most cyber-bullied around the world [as of 2018]. In one of the cases, we found that a girl in the 11th grade was a victim of ‘revenge porn’ as her intimate photos were leaked by her boyfriend because she told everyone that they were dating. These incidents have increased a lot more because of the pandemic given that more students are attending classes online. A study conducted during the lockdown by CRY on ‘Online Safety and Internet Addiction’ amongst adolescents in Delhi-NCR, reveals that one in every ten children had experienced cyberbullying and only half of them had reported this to anyone.”

But, if and when users wish to take action against instances of doxxing—whether informally or formally— doing so can prove to be difficult.

Once your information is ‘dropped’ online—that is, posted on social media, on a webpage, or circulated within seconds to a vast network—there is very little recourse to protect yourself. You would have to suspend your accounts on various platforms, change passwords, report pages, and so on.

You could also file cases with cyber-crime bureaus—but in India doxxing is not illegal. You would have a complicated and long-drawn litigation battle on your hands (as long as your doxxer is not anonymous, of course). As the Aapti representative notes, in India “There are no specific legal provisions to address ‘doxxing’. It typically is dealt with indirectly through laws against divulging sexually explicit content (The IT Act), voyeurism (Section 354C IPC and IT Act), defamation (Section 499 IPC), obscene content (Section 292 IPC), and online stalking (Section 354D IPC).”

Even within platforms, getting your personal information taken is not as simple. For instance, Google offers a “Remove my contact information due to “doxxing” from Google Search” service, which lets you request the removal of URLs which contain your personal information and the intent to threaten or harass you. However, at the same time, Google also reserves the right to decline your request to delete your own personal information in lieu of ‘Public Interest’ as it deems fit.

Approaching the ‘system’ can also be an intimidating space for an individual who’s been doxxed—especially if they’ve been historically disadvantaged by it. “What is important to note based on our research,” says the Aapti representative, “is that many victims of doxxing, cyberbullying, and harassment are reluctant to engage with the legal authorities. Particularly for more vulnerable communities, like women, this is likely to arise from a lack of trust or fear of further judgement or ‘slutshaming’. To make things worse, many people tend to not be aware of recourse mechanisms on social media platforms and even if they do, they avoid using them.”

The solution: ensuring that online security is more of a lifestyle change and not a one-off event

Technology is a murky, dynamic beast so much so that cybersecurity is regularly traded by users for convenience—most of us find following all the jargon and technical requirements exhausting. The lack of awareness is proved by the numbers. Aapti tells us that “An all-India survey by Social Media Matters on “Cyber Vulnerabilities and Parental Trust Among Youth in India” reveals that 53% of the respondents were not even aware of the existence of grievance redressal mechanisms that can safeguard individuals from trolling and cyberbullying and only 17% of the total respondents have actually leveraged these mechanisms.”

But, this article is not just being written to convey dark news of despair, but also hopes to provide you with some modicum of solutions if doxxed. Why? “It’s often difficult to actively prevent these incidents from happening, and while this is significantly harder to control on public fora, we first encourage users to exercise greater caution with who they interact and share sensitive material with,” says the Aapti representative. “There are also several digital habits that we hope will empower users to safeguard themselves, friends and family from these risks online.”

Simply put: getting better at protecting yourself online is more of a lifestyle change, as opposed to a one-off event. Kirit Sankar Gupta, an information security enthusiast, outlines the very, very absolute basics you can follow to protect yourself online to counter doxxing, as a regular user of social media.

For Kirit, perhaps the most important aspect of online safety is using passwords in a way that does not leave you vulnerable to every offended individual with some coding skills and a laptop. “No matter how inconvenient, do not use common passwords,” says Kirit. “Google the ‘most common passwords’ and if yours come up, it’s time to change it. Using two-factor authentication—wherein you link your phone number to your account—also helps it takes five minutes to set up and saves you a lot of trouble.”

The next step is managing your email addresses. “Have a second email address, one without any of your private information, and use that for your public profiles, pages, or for any place that requires your email address to sign up, or access information. This email address should also not have any [personal] identifiers (date of birth, name etc) on it.”

Then, there’s the phenomenon of Jamtara-style phishing, which is when “scammers use email or text messages to trick you into giving them your personal information.” Says Kirit, “Phishing is one of the most common ways in which devices are hacked into—so the best practice against that is to never, ever click on suspicious links. Do not open chats from unknown numbers and click on the enclosed links; don’t even open a link sent by friends on Facebook unless you are absolutely sure it’s safe.” If you are unsure as to how to decide whether a link is safe or not, Kirit suggests checking out these resources.

“Another basic practice is to switch off auto-download of media, especially on WhatsApp. This is one of the most common ways in which malware comes onto your phone,” adds Kirit. As a side note, switching off this feature on the phones of your parents and relatives will potentially save them from a few scams. Kirit also notes, rather ominously, “that if photos and videos end up infecting your phone, the safest solution is to give your phone to a manufacturer or destroy it. Many malwares infect your built-in processor and will not go away upon merely formatting your phone.”

.@WhatsApp needs to use AI in India just to auto detect and delete such good morning/evening/night messages. Penalize users or start handing out temporary blocks!

Cheap internet is a huge curse for middle aged Indian productivity ?♂️ pic.twitter.com/62x0T2VdGP

— Farhan (@farhanknight) August 7, 2018

Speaking of photos, Kirit informs us that “Every image contains certain internal data, including location coordinates and data on where and when it was captured, and the device on which it was taken. These are inherently detailed information sets that are even used by investigative agencies.” The problem is, we often share this information indiscriminately, without realising. “If you are uploading your photos on an image sharing platform like Imager, or anywhere where you are sending the full-resolution image, remember you will be passing on your image’s complete information,” says Kirit. “To prevent that from happening, you need to just run your photos through an EXIF data program that will clear your image of this information.”

Finally, for Kirit, “adding an adblocker extension that stops tracking ads, Facebook, and other website trackers from following you across tabs as you surf is a good idea.” The most robust open-source ad blocker Kirit recommends is uBlocker; the Firefox browser also has its own Facebook container to block Facebook trackers on your feed.

Why working towards a safer experience online starts with us

If you’re still with me, chances are everything that I’ve talked about sounds like quite a bit of effort. You may be in two minds about doing any of those things, mostly because privacy and convenience are (most of the time) on opposing poles of the techno-social experience. More importantly, it is exhausting for those from marginalised communities to think about more ways of protecting themselves in a world that seems tailored to trample you down.

But, systemic change doesn’t happen in a day. These habits need to be maintained over time, such that we begin to have more natural conversations around the right to privacy. And as tempting as it is in a dark year like this to become fatalistic about our dystopian reality, if at least one of my readers come back to any of the advice given here—we’d already have made a difference. And if you are by chance, intrigued and want to know further, this is a fairly good place to start.

Featured image courtesy of Joshua Gandara on Unsplash.

[…] to the International Council for Research on Women, in India, Google searches for information on doxxing, image-based abuse, and gender-based trolling increased during the pandemic. Of a random sampling […]

[…] https://thebastion.co.in/covid-19/doxxing-in-india-prevention-as-we-search-for-a-cure/ […]