Climate change is the biggest existential threat to mankind; the possible impacts are so severe and profound that they are even beyond one’s comprehension. The basics of climate change — how burning fossil fuels warms the planet — are not complicated and have been well-understood since the 1820s. It is our convoluted and fluttered response that has kept the masses at bay.

The initial warnings of climate change began to formally emerge more than half a century ago. In the 1960s, the first reports about the potential threat of fossil-fuel induced global warming began surfacing in the USA. In 1965, the report on “Restoring the Quality of Our Environment” by American President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Science Advisory Committee lay down the harmful effects of fossil fuel emissions. It warned that an increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide would act similar to a glass in a greenhouse by raising the temperature of the air beneath it.

“By the year 2000 the increase in atmospheric CO2 will be close to 25%,” the authors of the 1965 report concluded as they looked ahead 35 years. Close. They forecast CO2 to be about 350 ppm in 2000; it was 369.55.

But scientists. What do they know, right? #ClimateChange pic.twitter.com/FpjD6mpXTY

— jodyseaborn (@jodyseaborn) September 15, 2020

A report in 1968 by the Stanford Research Institute warned of the negative impacts that a warming Earth could expose humans to. The call for climate change grew stronger through the 1970s and 1980s, culminating in the formation of the IPCC and the landmark First Assessment Report that categorically warned of a growing greenhouse effect and laid out the potential threats of such warming.

A conversation around climate change had clearly begun.

Like many other late-nineteenth-century movements, this climate change discourse was closeted. Discussions took place within a community of scientists and policymakers largely from the Global North. Media coverage on climate change in India was near-absent throughout the late 1900s and early 2000s. A backtracking analysis of the media coverage around climate change from 2000- 2015 shows that there was barely any coverage between 2000 and 2010 on climate issues in Indian newspapers. Some international media sites would carry stories of how Indians are unaware of the impacts of climate change, which are incidentally going to affect them most adversely. Throughout 2010, India-related climate coverage was covered widely across international media outlets like the BBC, The Economist, The New York Times, and the Financial Times, among others.

Over the first half of the next decade, climate coverage remained sporadic, picking up pace only after the UNFCCC discussions on climate change in 2015. In May 2015, southern India was also hit by a deadly heatwave that took the lives of nearly 2,000 people within a matter of days. It jolted the nation’s conscience and media outlets began talking about the impacts of climate change. Voices linking the heatwave to climate change were still few and far between, but the idea had taken form. After the 2015 Paris Agreement, coverage around climate change picked up phenomenally, and there was no looking back.

A heat wave in 2015 melted asphalt in New Delhi, India, and caused the deaths of at least 2,500 people. From NYT pic.twitter.com/Ow4lo8u900

— Cherokee Group SC (@CherokeeGroupSC) September 11, 2016

The Coronavirus pandemic has shown us that we need to take action on pressing problems before they spiral out of control. Climate change is a problem that cuts across borders like no other; once its reality hits home, it may be too difficult for us to reverse the status quo. Sustained action on mitigating climate change is an immediate need.

Unfortunately, with the onset of the global pandemic, reportage on climate change have either reduced or been fragmented across narrow silos. The result? Climate change has been driven out of the global public conscience.

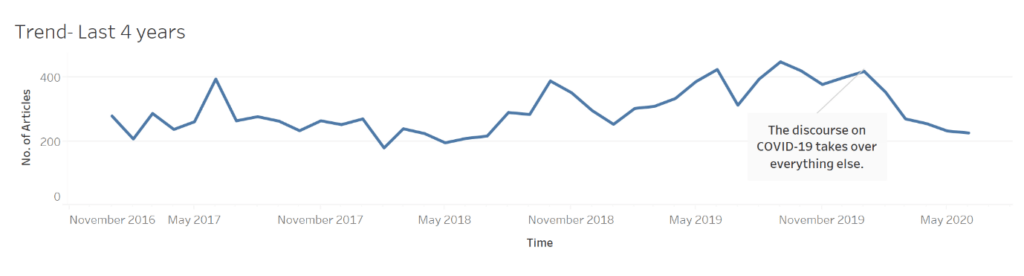

We scraped articles on climate change that were published over the last 4 years using this API offered by The New York Times. Here’s what we found.

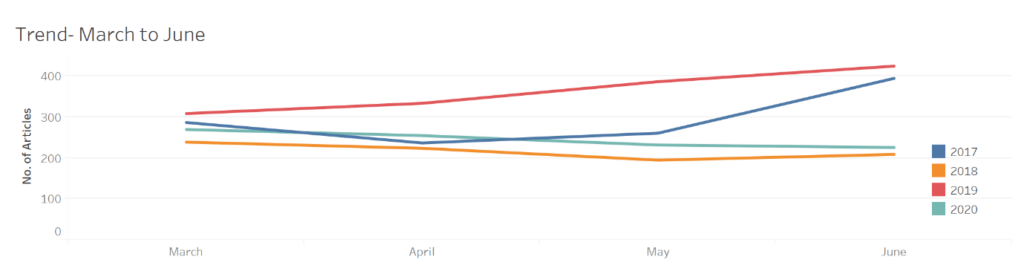

The visuals above and below should tell you that discourse on climate change has dropped substantially during this pandemic. More specifically, between March and June 2020, the amount of conversation, or the ‘noise level’, is significantly less than what it was at the same time in 2019.

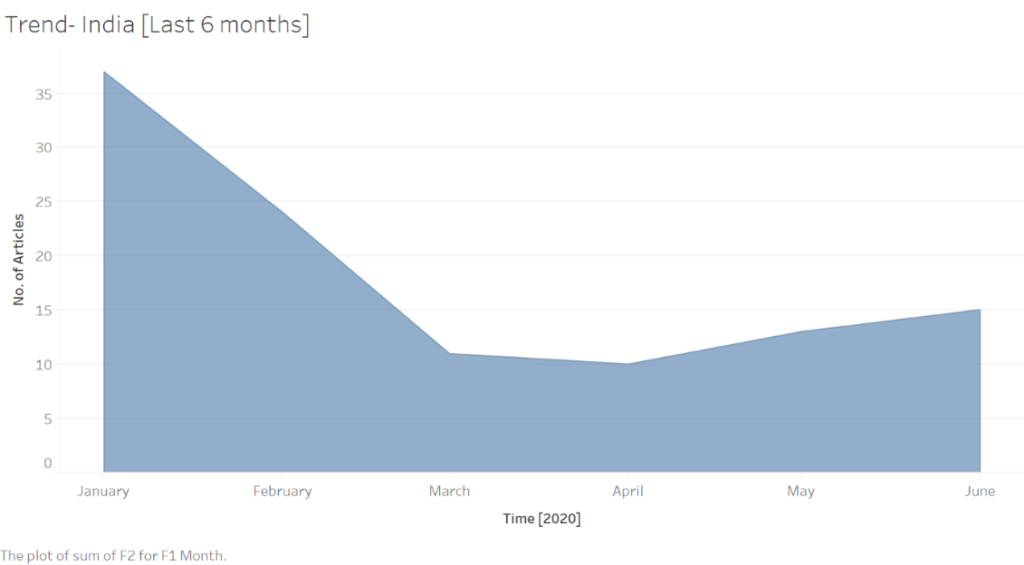

The situation in India today seems to mimic the global trend. Take a look at the figure below that shows the coverage of climate change in a major online Indian daily.

With each passing day, we are losing time. The stakes do not involve the planet’s survival. The Earth has seen far worse. It is the survival of human civilization as we know it which will be unable to absorb the shocks borne from the changes we are set to see by the end of the century.

There are a plethora of solutions to climate change. That being said, journalism will bring people together to actually carry out such solutions.

Many forces are responsible for restricting the depth and extent of our awareness of climate change as a phenomenon that requires immediate prioritisation. For starters, news media is primed to cover stories that are of immediate interest to the public and which are being discussed in the hallways of power. Climate science is also a complicated subject to discuss. Communicating a threat that is not immediately perceivable is always a difficult proposition; it doesn’t help that human beings are wired to make note of those challenges that can be sensed in a material sense and in the near-term. If scientists cannot discuss climate change in a language free of jargon, journalists find it incredibly difficult to point out causal relations between the environment and our changing climate.

The media has proven its importance during the pandemic, with 24/7 coverage keeping citizens informed and inducing awareness on hygiene and self-isolation practices. The media can similarly positively impact action on climate change, both from governments and citizens. We need even more conversations on the impacts of clean energy and energy security on mitigating climate change. Going forward, the instances of extreme climate events will become the ‘new normal’. More awareness, discourse, and debate on climate change problems and more importantly, solutions, is the need of the hour and it is that which is ultimately our way out of this crisis.

Featured image: “A ‘climate change’ clock was recently unveiled in Manhattan. It shows us how much more time we have until the effects of climate change become irreversible. Courtesy of Given Edward. | Views expressed are personal.

Very insightful Article