Written by Tanay Gokhale

We have all heard, spoken and wondered about India’s failure to produce Olympic medal-winners proportional to its population. With an impressive run at the Asian Games 2018, anticipation around Tokyo 2020 runs high.

In India, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is defined as “corporate initiative to assess and take responsibility for the company’s effects on the environment and impact on social welfare”. Often going under the radar, sports development was also a sector permitted for CSR activity alongside education, poverty alleviation, healthcare, etc. Initially, only “training to promote rural sports, nationally recognised sports, Paralympic sports and Olympic sports” qualified as CSR. In 2015, the clause was amended to include “construction, renovation, maintenance of stadiums, gymnasiums and rehabilitation centres”.

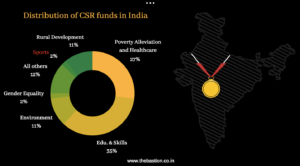

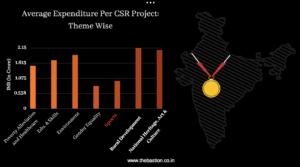

However, even after broadening the scope, CSR spending on the sports development sector has been negligible in comparison to others. While in absolute terms, the figures appear to grow year-on-year, sports sits at the very bottom of the pile.

CSR regulations are governed by the Companies Act 2013 and the CSR Rules, which came into effect in April 2014. It mandates companies with a net worth of ₹500 crores or more, or a turnover of ₹1000 crores or more, or a net profit of ₹5 crore or more in an FY to spend 2% of their net profits on CSR activities.

Given its potential to offer athletes a safety net that can breed future talent, why is CSR spending so low — especially in an industry that thrives on companies’ piggybacking off of huge athletes for their niche adverts? Moreover, how can strategically spending CSR funds improve Indian athletes’ chances of bringing home international spoils?

Sports Excellence

One of the two broad ways in which corporates contribute to sports development is by providing assistance — either in kind (apparel, training facilities) or financially — to promising athletes. Some companies like TATA and Jindal South West choose to nurture talent at their own training centres established as a foundation. Still more common is the practice of investing in not-for-profit organizations like Olympic Gold Quest (OGQ), Anglian Medal Hunt Company (AMHC) and GoSports Foundation, which in turn use this money to help the athletes they have signed on.

According to Ms Sulagna Datta from Sattva Consulting, “Sports excellence is often a preferred route for CSR, compared to investing in training facilities and other sports infrastructure. For the latter, there is no definite indicator to report progress. But with sports excellence, the companies can report how their contribution directly impacts prospective medal-winners.”

With a growing base of experienced training professionals at OGQ, GoSports Foundation and AMHC, she expects more and more companies to sponsor athletes in the years to come. “Sports as a sector often loses out to other sectors like education, poverty alleviation, healthcare and nutrition as they have a stronger emotional connection with corporate upper management. In our experience, if a company is investing in sports development, it is more often than not because members of the upper management are passionate about sports. The importance of sport and its potential to add value to society is not as easily apparent as other sectors. Hence, it all boils down to whether someone in upper management is interested in sports or not”, she adds.

Inclusive Sports, Grassroots Sports Development

Many firms go the other way. Instead of making valuable resources available to selected athletes with promise, they choose to make the sport accessible to as many as possible. This involves facilitating the provision of basic training, nutrition and infrastructure at the very grassroots level. These initiatives (often run by independent not-for-profits) aim to generate interest for sports amongst sections of society that do not usually have the means to play at an amateur level.

Though the total volume of funds is lower, this sector of inclusive sports and grassroots sports development attracts funding from more companies, in comparison to sports excellence. Also, such initiatives garner more interest when clubbed with other education initiatives. According to Ms Datta, “Because many companies are already running education campaigns as their CSR, it often helps if sports development initiatives piggyback on education; if companies start a complementary sports development program, it boosts attendance rates, ensures a more well-rounded schooling experience and serves as a personality building exercise.”

With that being said, corporate funding is still hard to come by in the grassroots sports sector. Pradyut Voleti, founder of Dribble Academy believes that the reasons for India’s stunted financing of sports are multifold. The first is the imbalance between funding for the two different sectors of sports development.

“Sure, investing in sports excellence is very important and crucial to securing medals at the highest level of competition. But we urge companies to groom and invest in talent at lower levels of competition…providing access to sports training [at this stage] is critical to talent development and excellence in sports for the future. Thus, there needs to be a balance in CSR funding for sports excellence and grassroots sports development”, he tells us.

To confound matters, corporate engagement with their own CSR programs is often superficial

“Companies need to look beyond what will get them more bang for their buck and choose to fund projects which will have a greater impact in sports development in India. To that end, they need to realize that sports help children in as many ways as healthcare, education and other training”. Albeit an organization in its nascent stages, Dribble Academy has already churned out basketball coaches and national team prospects; its worth as an organization lies not only in the fact that they give children the opportunity to play but also in that they skill children to potentially secure gainful employment.

Another problem that might seem innocuous is the involvement (or lack thereof) of the private sector even outside of CSR. In the USA, companies like Nike and Adidas conduct specialized training camps and incorporate grassroots sports development as part of their marketing strategies. In India, however, companies only focus on securing sports superstars to endorse their products.

Ms Datta resonated with Voleti, in that “companies often have greater freedom and hence, a greater potential to invest in sports development, through the allocation of funds for marketing expenses. Brands like Nike and Adidas can allocate funds for infrastructural development, sponsorships in the form of apparel, equipment, etc. for both talent development and grassroots sports development, simultaneously creating a stronger brand presence and visibility for themselves.”

Picking up the Responsibility

As Voleti pointed out, one way to generate greater interest in sports development is to popularize sports at all levels. Thus, district and state sports associations need to be more proactive in organizing and promoting sports meets at their levels. They could also consider partnerships with private sector companies — especially those in the sports apparel, equipment and management spaces — to pave the path for corporate funding.

India is one of the few countries where corporate social responsibility has been crystallized into a law that is mandatorily enforced. Yet, CSR laws are still in its infant stages; corporates are still figuring out the breadth of its implications and the different ways in which tangible impact created through their spending can be used to build a better image for themselves.

That being said, for a country that often collectively wonders about its sports potential, CSR spending in sports development is seriously low. There are big fish to fry, like the poverty alleviation, education and healthcare sectors, which are certainly vital to a child’s development. Just remember that it does not bode well for Indian sports that very few corporate entities realize the value of access to sports and the role that they can each play in creating world-beaters.

Featured image courtesy JSW

[…] the data shows that as of 2019, CSR contributions to sport only amount to about a paltry 2% of all CSR funds. Attaining the Industry status would provide ensure special incentives to investors in the sports […]