It’s a busy intersection at Himachal Pradesh’s Palampur. In the backdrop of this town, the Himalayas stand tall adorned with the winter’s snow, and at the intersection in the morning, HRTC buses make brief stops letting passengers off and on. Against this daily bustle of vehicles and opening up of shops, a peculiar vehicle stands out. It is difficult to miss. A three-wheeler, it is mostly yellow, with two separate bins trailing behind it. The contents in each bin are defined by its colour—green for wet waste, and blue for dry.

This eco-friendly rickshaw soon drives away from the intersection and goes around the municipality limits of Palampur, as well as the neighbouring panchayats of Aima and Ghuggar, for the door-to-door collection of municipal waste.

This e-rickshaw, along with a tractor, collects wet and dry waste from homes, markets, hospitals, and hotels in the region. “We make two rounds in a day, one in the morning, and then one in the evening,” explains Govind, as he parks his tractor in Aima, a few kilometres away from the town of Palampur. He has been contracted as a driver with Municipal Corporation (MC) for the last year. His tractor is now full of bags of segregated waste. He begins to unload the waste. A few young men appointed by the Municipal Corporation unload about 1.50 tonnes of garbage per day, that Palampur alone is estimated to produce.

This is the Waste Management Plant in the village of Aima, adjacent to Palampur. Aima is the first such panchayat in Himachal Pradesh to install one.

In the past few years, increasing waste and inefficient disposal has been a mounting issue in urban centres of the Himalayan state. Ground reports from Kullu-Manali, Shimla, the industrial hub of Baddi, and the Smart City of Dharamshala all report the similar trend of unscientific and unsegregated waste dumping in dumpsites.

You May Also Like: Living in Toxicity: Industrial Pollution in Himachal Pradesh’s Baddi

Such dumping of municipal, bio-medical, and industrial waste in an ecologically sensitive area like the Himalayas often impacts many other resources and allied eco-services. That this waste dumped in dumpsites can directly impact resources like water and soil in close proximity, is not a far off possibility. Notably, in a paper that tested the groundwater and soil quality of areas near the Pallavaram solid waste landfill site in Chennai, it was found that the presence of alkalinity, calcium, magnesium, chloride, nitrate, copper, and dissolved solids in the water samples were all much higher than the desired limits. Given that rivers, khads (streams), and kuhls (community-owned irrigation channels) are the lifelines of everyday life in Himachal, such pollution is a grave threat.

Aima’s Waste Management Plant, which is a joint venture between the Municipal Corporation Palampur and the Gram Panchayat Aima offers lessons on how such waste can be dealt with efficiently, while also putting forth the importance of improvised, local experience in waste management.

But most importantly, it puts out a message loud and clear—decentralised waste management is the way to go.

Processing Waste in Aima

“Initially, we were just burying the waste in a landfill adjacent to where the plant operates. But, we knew that this wasn’t the most sustainable option,” says Sanjeev Rana, the former Pradhan of the Aima Panchayat. In fact, up till 2017, all the waste generated by the Palampur MC was being dumped into the adjacent village of Lohna. But, as Palampur’s Action Plan on Solid Waste management shows, in the monsoon of 2017, a cloud burst washed away the garbage in Lohna, creating a nuisance for people residing close by. As Lohna’s villagers started speaking up against the dire garbage situation there, the MC was forced to look for alternatives.

“So, when I got a chance to be a part of national seminars, we were exposed to different methods and techniques that can be used to deal with kitchen waste and plastic. We decided to give them a try,” Sanjeev continues. Setting up a mechanism to deal with the waste produced by Aima’s 7000 residents was Rana’s main motivation to fight the Panchayat elections. When he succeeded in 2016, installing the Plant was his first priority.

Once the waste is unloaded at the Plant, it goes through a round of segregation followed by extensive treatment. The wet waste is composted by the composting machine, and the manure is then often collected by villagers living close by for their use.

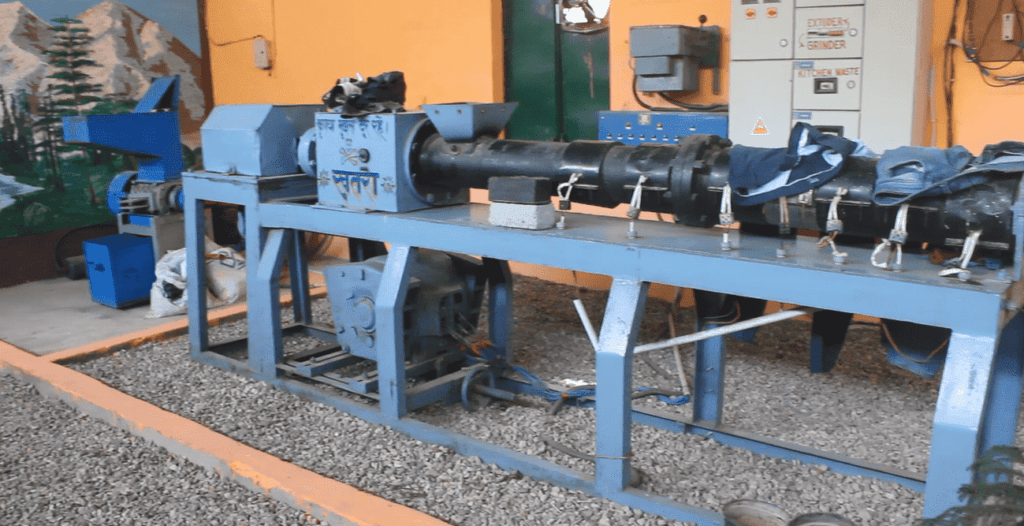

Bio-medical waste and sanitary pads are incinerated by the incinerator, while plastic material is ground into granules by a granulator. Most interestingly, a binder is expected to convert plastic powder into bricks!

“We did a lot of our own research on the internet to understand which machines would be the best,” explains Rana. “We even went to Delhi and Noida to see how similar plants operated and to understand what impacts they are observing there. All of this was paid for out of our own pockets.”

All these machines operate in a compact space. Unlike other waste treatment plants and landfills, no odour is present in the air here.

Since the plant a joint venture between the Panchayat and the MC, the MC provides a sum of ₹40,000 per month to the panchayat to support its operations. Additionally, hotels and shops from where the waste is collected are charged separately, while each house also pays ₹350/year for these services.

The efforts did not stop at installing the machines; the municipality and the Panchayat also developed campaigns to raise awareness on segregating waste at the individual level. Rallies, complete with posters and announcements regarding the waste issue and need for individual action, made their way on the roads of Palampur and concerned Panchayats.

The Plant even made an interesting debut elsewhere: When the State Expert Appraisal Committee of Himachal Pradesh approves a housing project, it grants them environmental clearance on certain conditions, the first one of which is now often this: “the technical experts of project proponent shall visit Aima Panchayat…for demonstration of solid waste management plant and will replicate this model in their project as per the required capacity.” Such has been the perceived success of this Plant. The Panchayat even bagged the second place for Himachal Pradesh Environment Leadership Awards 2018-19.

Gaps that Need Filling

It does not take too long to notice that while the composter is working its hours, the grinder and binder machines to manage the plastic waste lie idle. “Both these machines require immense amounts of energy to run to convert plastic into powder. But, the plastic that the plant has been receiving is not enough to make enough plastic bricks to sell,” explains Albon Bonny Mitchell, who has been associated with the NGO Palampur Welfare Environmental Protection Forum since 2011. “The fewer quantities of bricks produced do not cover the operating costs of the machines themselves.”

When they tried operating the machine during the early months, they found that the electricity bill was around ₹11,000 for operating the machine for just 2 hours.

In lieu of this, now the plastic bottles and other malleable plastic are pressed into bundles and then sold to the recyclers. “While this Plant has been hailed as a model, there is no doubt that there is a constant need for innovation in these techniques. We are constantly trying to figure out lesser expensive machines that would do the job as efficiently,” admits Rana, referring to the current unviable model of the plastic brick making machines. Rana resigned from his post as a Pradhan last December. He is now the State Coordinator from Himachal Pradesh for the Swachh Bharat Mission, which gives him the opportunity to explore other such best practices. Mitchell adds, “After all, Rome was not built in a day.”

The constant need then, to monitor what works and what doesn’t becomes especially important since this model is expected to be rolled out in other Panchayats in Himachal Pradesh. “A High Court order declared to use this model everywhere in the state,” mentions Rana. “At present, work for similar projects has begun in seven sites around Palampur, including the village of Khalet.” Neighbouring Khalet had been in the news for the efforts of its first woman Pradhan, Hema Thakur, who got a similar plant installed after seeing Aima’s experience.

In these new sites, the machine to make plastic bricks has not been installed until a better alternative is found.

As this model in Aima gears to be scaled up, questions of economic feasibility and consecutive environmental impacts need to be assessed critically. “This Plant might be only a drop in an empty pond,” Mitchell comments. “But, at least it’s the first drop.”