Growing up, I would never have a fitting response for my school friends when they laughed at me for spending hours in line to use a community toilet. And while their teenage laughter may well have been innocent, it was still a reflection of how privileged society viewed “people like us”. Besides the physical and mental toll of waiting hours to use a toilet in our basti, I was also losing precious time, which other children my age spent on their development. As one gets older, such experiences build up to mental distress that remains undiagnosed but leaves deep injuries.

The majority of research around mental health is written in a Western tongue that does not respond to the diversity and complexities of Indian society. Nomadic and denotified tribes (NT-DNTs) are one of the most vulnerable communities in this country. They don’t have houses, let alone toilets. Criminalized, ostracized, and without legal protection, the mental well-being of such historically marginalized communities are rarely considered, which is a grave social injustice. I use ‘justice’ in the language of our Constitution, which has consciously taken a stand to ensure the rights of self-preservation, participation, development, and leadership to every Indian citizen, including those who stand at the very end of our social hierarchy.

In order to ensure this, the current scope of mental health itself needs widening. From being a space for individual counselling, relief, guidance and treatment, it should include the concept of mental justice, because communities’ dignity is core to their members’ psychological well-being. In fact, marginalized communities — especially the women in them — have already developed community knowledge on coping with mental health, and there is value in learning from these strategies.

Manufacturing Mental Terror

The oppression and disenfranchisement of nomadic and de-notified tribes in (NT-DNTs) began with the passage of the Criminal Tribes Act in 1871 by British rulers. Led by the likes of Umaji Naik (pictured right) from the Ramoshi community, NT-DNTs were one of the first to fight for swarajya. The 1871 Act labelled these communities as ‘criminal’, snatched their land and homes, and forced them to migrate.

The subsequent violence inflicted by the British consisted of economic, social, physical and political exploitation. But this was alongside another form of exploitation — that of mental oppression. How else was it possible to forcefully take land from communities who were strong enough to rise against the mighty British? How were they beaten into submission?

Any group oppression begins with mentally oppressing members into feeling weak; this is sustained over decades, and eventually normalizes discrimination and violence inflicted upon marginalized communities. I myself belong to the Gadiya Lohar Ghisadi nomadic community. We have traditionally been ironsmiths who melt iron to make tools and weapons.

When I read and hear the limited histories available of my people, it becomes clear that by overburdening members with insurmountable problems over generations, a mental terror can be created. It is one that forces community members to lose hope and courage.

Indramal Bai burnt herself when 3 policemen harassed her for bribes to not charge her with theft. Police inquiry called it “drunken accident”. In high court, police falsified own claims, govt counsel said she was from tribe of criminals. https://t.co/GUH5mQPu1O

— Article 14 (@Article14live) May 30, 2020

Any injustice inflicted upon individuals can never be seen in isolation. The suicide of Dr Payal Tadvi, for example, affects the collective mental dignity of the entire Bhil Muslim tribe. With each blow, the social insecurity experienced by communities deepen, and it is necessary to address this collective mental trauma from the perspective of delivering mental justice.

Collective Expectations and Mental Mob Lynching: Women Worst Off

I’ve coined a concept that may help in understanding how such degrees of deprivation have been made possible through years of exploitation. It is called “Collective Expectations”. Collective expectations are expectations of the collective majority towards a minority or individual which incapacitates them, dehumanizes their existence, or causes some other form of harm. Such expectations are politically designed, and are not imposed spontaneously.

Let us take the example of the behaviour of mainstream society towards NT-DNTs living outside a said village or town. Despite having been ‘denotified’ by law, they are still seen as criminals and are discriminated against. During lockdown, many leaders from the NT-DNT community felt that villagers viewed them with suspicion, as if they were “carriers and spreaders of the coronavirus”.

It is said that we can make even iron sweat. Our people have never asked anyone for anything. But what do we do [in a pandemic]? Villagers don’t give us shelter even during lockdown… they abuse the women from our community if they enter the village for using the toilet. Where will they go?

—An NT-DNT community leader in Satara, Maharashtra

Besides digital connectivity being a far cry, the sheer state of emergency caused by a pandemic has created immense mental distress for NT-DNTs and other vulnerable communities. The few primary resources they subsisted upon suddenly became all the more precious in the wake of this additional calamity.

Anubhuti, an organization I founded in 2016, is working in collaboration with these communities for securing their mental justice. During our relief operations, we reached 4000 families of NT-DNTs and another 1000 from other marginalized groups across 15 districts of Maharashtra with ration, bank transfers, and phone counselling, all of which involved hundreds of repeated calls. We made special efforts to reach pregnant women, single women, women-headed households, and made it a point to speak to women of the household as much as possible.

We found that women were staying hungry the most. Bear in mind that these women already face severe issues of malnutrition, anaemia, etc. Their deprivation during the pandemic will lead to long-term public health issues.

This pandemic has hampered the education of girl children across the country, but especially so for some of the first-generation girls who are finishing school. They have worked very hard to overcome generational hurdles; now, they find themselves stranded in classes 9 and 10. This insecurity has led to an increase in cases wherein girls are married off at very young ages. We have seen this across Maharashtra.

“If women find themselves weak, it will affect our economy badly”, says a mother of two, fully aware of how the pandemic threatened the survival of her community. This is because the women of NT-DNT communities carry out most of the tasks of their labour, from blowing the bhata (a hand-operated bellow used to blow into the stove which melts iron), to repairing tools, and doing roadshows.

Women and girls tell us they are afraid to work alternate jobs. Those working in the unorganized and informal sectors are already feeling desperate as they find themselves in an increasingly competitive job market. “We already have to fight at home to be allowed to work outside, but now I have no choice. As the work [opportunities] dwindle, I feel under pressure to work without raising my concerns, even if I worry about my own safety”, said a young woman from Satara district.

Women are delivering community mental justice at the grassroots

It is a common sight to see women in NT-DNT communities sit together and talk about the problems they are facing — from domestic issues and gendered violence, to caste discrimination. If you think about it, women have always developed informal money-lending systems for supporting each other financially; locally, these are known as bhisi groups, and ‘self-help groups’ across general literature.

Most of these women are not literate, and continue to remain uneducated. But they have developed knowledge through their lived experience, and they share these amongst one another as strategies for survival and psychological support. However, because they are not college graduates with degrees to their name, their wisdom gets discounted despite the fact that this is what has kept them alive in the face of decades of oppression.

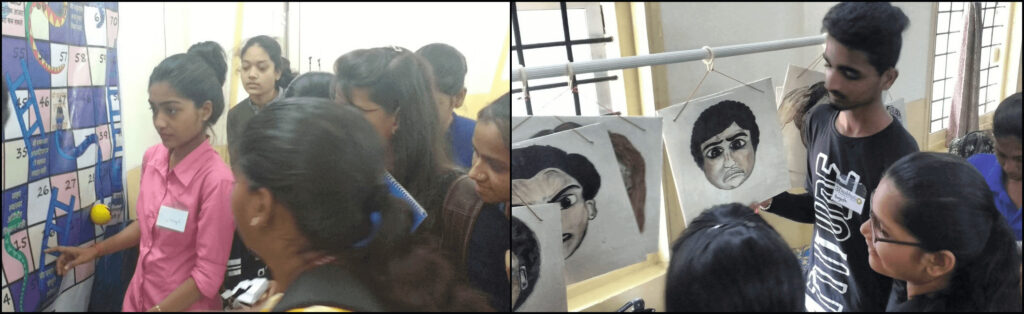

At Anubhuti, we are building on leveraging the strategies of these women for coping with mental distress and its factors. We have started community-based counselling centres in Thane district, where along with easy-to-understand mental health literacy, support is offered in various areas such as domestic violence, sexual and reproductive health issues, career and education-related stress, financial problems, addiction, and others major factors of mental distress among vulnerable communities. Anubhuti’s interventions have seen healthy community participation; trained youth leaders identify and refer persons suffering from mental distress to the centre, help document their case sheets, follow up for further sessions and so on.

“Mann Mela”, a ‘mental health fair’ module, has been developed to impart mental health literacy and support at the grassroots; the module is led entirely by trained youth. It replicates games and various other interactive stalls as in a fair, all aimed at improving mental health literacy such as how to identify an issue, coping strategies, healthy habits, etc. All this is available in a simple, contextualized language.

Towards securing the mental justice of vulnerable communities

The way forward is quite clear, if not easy to tread. There is much deprivation amongst members of NT-DNTs and other historically criminalized communities. In fact, there is no problem that does not affect our well-being. Delivering mental justice, then, requires a 360-degree approach. Policies and services across every sector should account for their impact (or lack thereof) on the collective mental health of communities like ours.

Institutions and stakeholders that operate with a universal approach, such as the police, schools, ASHA workers and so on, already have experienced workers who are women leaders at the grassroots level. They reach households on a regular basis and must be recognized as core mental health service providers. Mental health literacy and sensitization should be added to their training curricula and work responsibilities, along with an adequate increase in their compensation.

Every mental health practitioner in India must recognise that mental distress is not only induced in individuals, but also in communities at large. Practitioners will have to increase their risk-bearing capacity and acknowledge that riots, atrocities, caste discriminate and gender-based violence create mental health problems. Doctors must support clients facing mental health problems due to such issues by widely interpreting the 2017 Mental Healthcare Act 2017 from a framework of collective expectations and mental justice. Curriculum and research on mental health must heavily incorporate fieldwork alongside the study of gender, caste, ethnicity, religion, etc. These markers form the bedrock of communities and are key to sharpening a practitioner’s ability to diagnose and treat mental health issues.

India’s mental health movement needs to be equipped to represent its specific needs internationally, in the interest of widening global mental health indicators. For example, the mental health indicators in the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals are very limited (SDG-3). They only address reducing mortality due to abuse, or suicide.

Just as matters of gender, caste, and class are taken up across movements, the goal should be to ensure that securing mental justice — especially for those belonging to vulnerable communities — is a point of concern in any matter. After all, any country with poor mental health and unfulfilled human potential will find it impossible to deliver progress to those last in line.

Editor’s Note: This story has been written with translation support from Amrita De. You can learn more about Anubhuti’s work by visiting their website or write to Deepa with feedback and questions at [email protected]

Featured image courtesy Deepa Pawar