In February of 2020, I visited the Varanasi Multimodal Terminal on the Ganga river in Uttar Pradesh.

This multimodal terminal—which facilitates road, rail and waterway connectivity—was inaugurated in 2018 under the World Bank-funded Jal Marg Vikas Project for increasing the capacity of the National Waterway-1 on the river Ganga. The Inland Waterways Authority of India (IWAI) that is developing and regulating the Project under the Ministry of Shipping, Ports, and Waterways hopes that the JMVP will present an “alternative mode of transport that will be environment friendly and cost-effective (..) [and] contribute in bringing down the logistics cost in the country.”

So, as I entered the Varanasi terminal two years after its inauguration in 2018, I expected to see a barge parked by its high-level jetty on the river Ganga, with cargo being loaded and unloaded, and the bustle of passengers making use of the low-level jetty.

Instead, I was met with two empty trailers on the terminal’s vacant jetties. Hardly anyone was in sight.

This pattern of inactivity repeats itself across the Jal Marg Vikas Project’s other initiatives too—especially at the Sahibganj Multimodal Terminal in Jharkhand.

◯◯◯

The Centre’s flagship Jal Marg Vikas Project (JMVP) was set up to catalyse policies concerning India’s National inland waterways. Announced in 2014 by then Finance Minister Arun Jaitley, a contract was signed with the World Bank to support the Project both financially and technologically in 2017. The revised estimated cost for the JMVP is ₹4,633.81 crores, with the World Bank’s loan accounting for USD $317.22 Million (approximately ₹2,376 crores) of the sum.

Since 2016, the National Waterways Act has been proclaimed as a ‘game-changer’, after it declared 111 National Waterways on almost all major rivers, creeks, canals of the country. In the 2022-23 Union Budget speech, waterways were named by the Finance Minister as one of the ‘seven engines’ of the Prime Minister’s GatiShakti Transformational approach. One hundred PM Gati Shakti cargo terminals were also announced wherein facilities to handle different modes of port activities would be created over the next three years. All this is to say that the multimodal terminals being developed on the waterways of the river Ganga are setting the tone for similar infrastructure in different parts of the country. But who stands to gain and lose from them?

Back in 1986, the Ganga-Bhagirathi and Hooghly river systems flowing from Allahabad in Uttar Pradesh to Haldia in West Bengal were declared as ‘National Waterway -1’ (NW-1) to facilitate the movement of goods and passengers within India’s inland waterways. However, the project was unsuccessful, with most freight being moved within the tidal stretches of the Hooghly in West Bengal.

Three decades down the line, the JMVP aims to enhance the efficient transportation of bulk and hazardous goods on the NW-1 using vessels with a capacity of 1,500 tonnes or more in an environmentally sustainable manner.

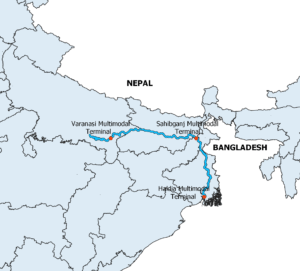

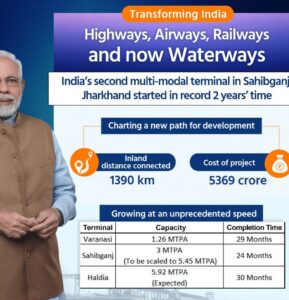

With the Project slated for completion by December of 2023, three Multimodal Terminals (marked in red) have already been constructed along the Ganga. The first, inaugurated in 2018, is in Uttar Pradesh’s Varanasi and was built at a cost of ₹183 crores. The second, at Sahibganj in Jharkhand, was inaugurated in 2019. Built with the capacity to handle 3.03 Million Metric Tonnes of cargo per annum (MMTPA), it cost ₹280 crores. The third, in West Bengal’s Haldia, cost ₹517 crores, with civil construction work currently underway.

The JMVP has two additional components: the first, centred around private interests, is concerned with moving large barges (which are long flatboats for carrying freight) and building large multimodal terminals and intermodal terminals. The second component concerns itself with building small community jetties under its Arth Ganga plank.

“The Multi-Modal terminal at Sahibganj will open up [the] industries of Jharkhand and Bihar to the global market and provide Indo-Nepal cargo connectivity through [the] waterways route,” reads a PIB brief from 10 October 2019. “It will play an important role in [the] transportation of domestic coal from the local mines in [the] Rajmahal area to various thermal power plants located along [the] NW-1. Other than coal, stone chips, fertilisers, cement and sugar are other commodities expected to be transported through the terminal.”

The Detailed Project Report (DPR) of the Sahibganj Multimodal terminal projected cargo handled at Sahibganj to grow from 1.87 MTPA in 2015-16 to 2.50 MTPA in 2020-21. However, the first two years of operations do not live upto these projections. After its inauguration in 2019, only 18 cargo vessels have ever been handled at the Sahibganj Multimodal Terminal. By the Ministry’s own admission, no cargo vessels have been handled here throughout this financial year (2021-22, up until now). It is highly unlikely that the terminal will recover its annual operation and maintenance costs, which according to the DPR, are estimated to be ₹27.13 crores.

The (infrastructurally and financially) massive multimodal terminals for Sahibganj and Varanasi were constructed for private players to operate. Tenders were floated twice for the terminals but were cancelled both times due to a lack of interest shown.

The inhibition of the private players to take MMTs off the hands of the government foregrounds the challenge these terminals face to become operational in an efficient and beneficial manner. Yet, despite these realities, the expansion of the Sahibganj terminal has been proposed by the IWAI across three phases, increasing its capacity to 9.5 MMTPA at a cost of ₹1,470 crores. The underutilization of these MMTs coupled with the central governments’ eagerness to continue developing them calls for concern regarding its cost-effectiveness, requiring an immediate, independent, and comprehensive assessment.

◯◯◯

Besides its significant costs to the exchequer, what is of arguably greater concern is the JMVP’s lack of regulatory oversight, apparent in its reluctance to meaningfully include the local people and ecology directly affected by developing inland ports. The Sahibganj Terminal, for example, exhibits sunk costs of two other kinds. There have been heavy social costs paid by the local population, with around 485 families in Sahibganj being displaced for the project. Alongside this, there are costs borne by the environment. While the JMVP has been presented as an environmentally friendly project, the risks it poses to aquatic ecosystems and riparian communities remain underacknowledged.

The Inland Waterways Authority of India claims that inland waterways projects have less adverse social impacts, as the scale of land acquisition is smaller as compared to other infrastructural projects.

But in order to construct an inland multimodal terminal, develop complexes for maintaining vessels, providing parking facilities, freight villages, and road/rail linkages to industrial units, you need land. As for the Sahibganj MMT in particular, 192 acres of land was acquired through the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013. 485 families were identified as ‘Project Affected Families’, which means they were entitled to resettlement.

Yet, according to the January 2020 JMVP Project Implementation Status report, 68 families were yet to receive their relief and rehabilitation packages. 25 houses were constructed at the time of writing the report, and 8 families had relocated. A contract was awarded in July 2019 to construct 392 houses; work commenced by January 2020 only for 109 dwellings.

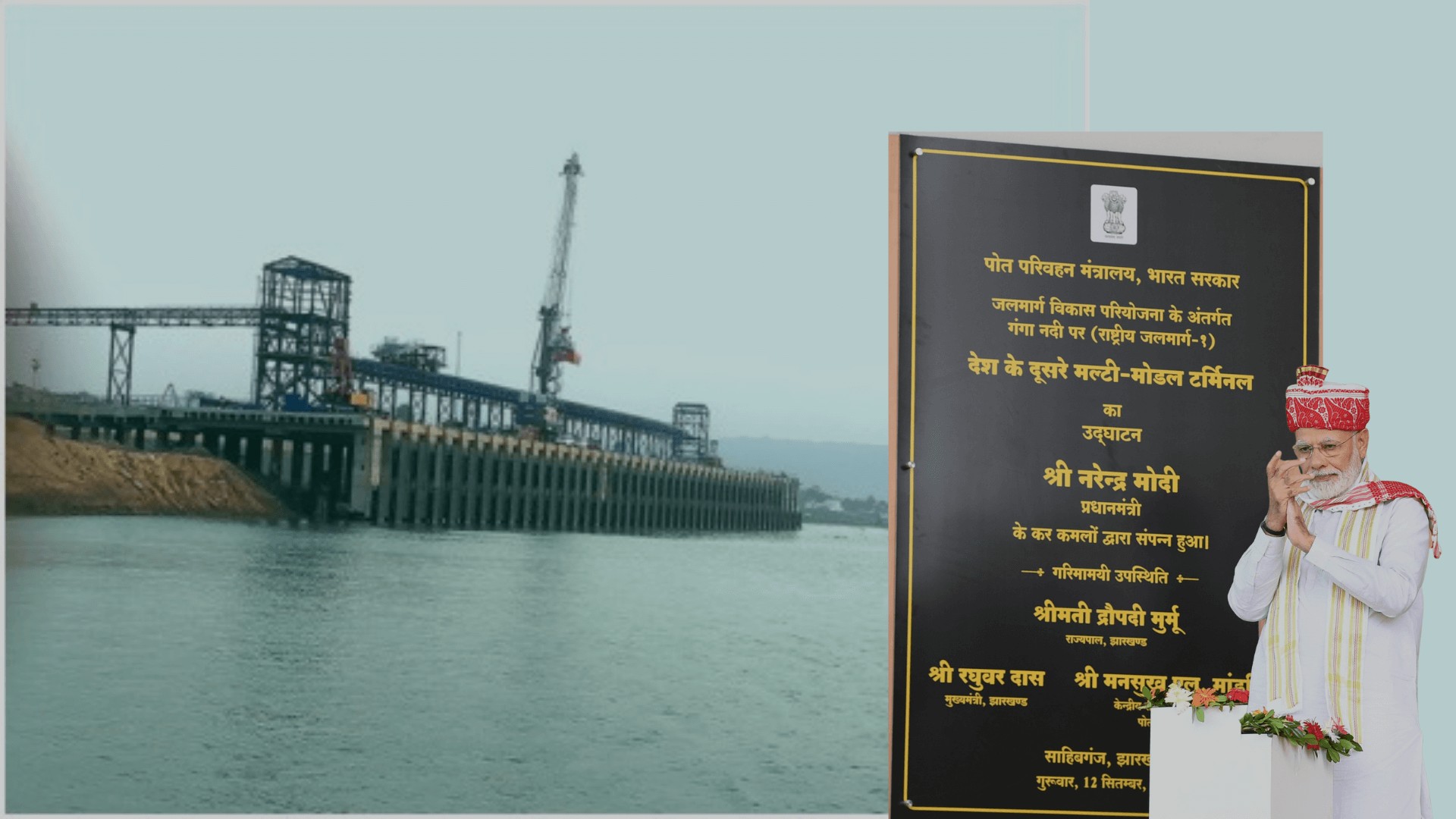

All of these steps took place three months after the inauguration of the Sahibganj terminal—which is claimed by the Ministry of Ports, Shipping and Waterways to have been constructed in a “record time”.

“The area where the resettlement colonies are located is low-lying,” says Divakar Yadav, a local from Sakrigali in Sahibganj. His home was uprooted to improve road connectivity to the MMT. Over a lengthy phone call, he expressed his distress over the hastily-constructed resettlement colonies. “It was supposed to be filled, levelled, and then left for around two years [so that] the land would become stable for construction. But [the government] constructed the resettlement colonies without waiting for the land to become fully prepared for construction. Whenever it rains, there is a flood-like situation here,” he tells us.

Yadav claims that many people are still waiting for their compensation. Many others are still waiting to be recognised as Project Affected families. In a report by the People’s Resource Centre, both the local population and Project Affected Families of Sahibganj MMT have claimed that the compensation given was not at par with the market rate of the land. They also argue that there were discrepancies with the rehabilitation process, to show a fewer number of families listed as Project Affected families.

The day the Sahibganj MMT was inaugurated in 2019, many civil society organisations released a joint statement urging the Prime Minister to address its social and environmental concerns. Yet, after January 2020, the IWAI stopped releasing detailed project implementation status reports altogether. It instead released status updates on the JMVP, with scant details on the overall project, and no update whatsoever on the relief and rehabilitation processes related to the Sahibganj Multimodal Terminal.

At the time of writing this story, the IWAI’s Sahibganj office was contacted for comments on the matter, but to no avail.

◯◯◯

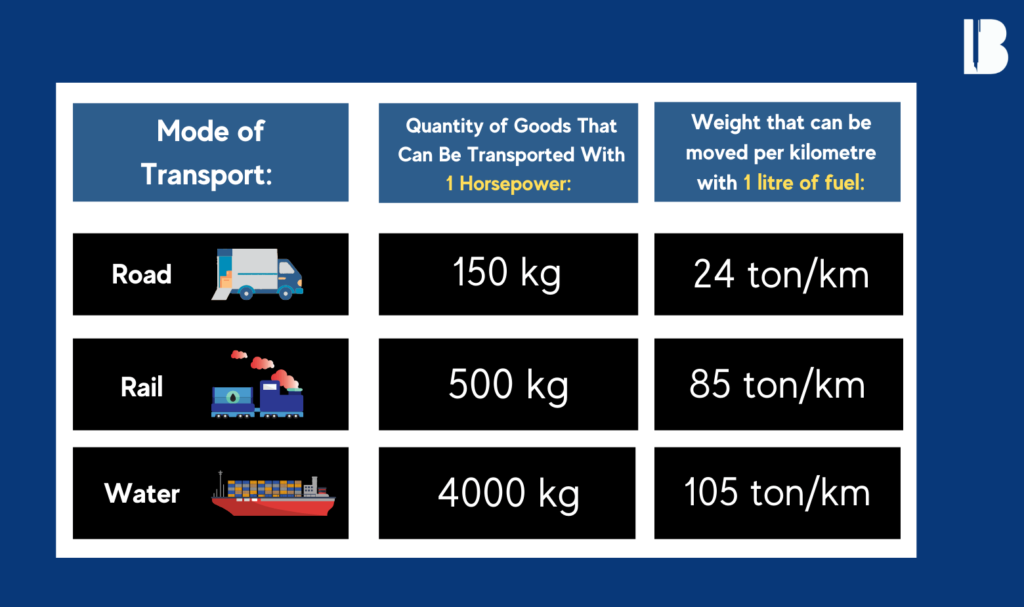

The IWAI claims that shifting bulk and hazardous goods on inland waterways can lead to significant savings on fuel. This results in reduced greenhouse gas emissions and is cost-effective for traders.

However, the benefits of transporting freight via waterways do not come without environmental costs.

Developing inland waterways requires the creation and maintenance of a navigation route in a river that is adequately wide and deep. Most Indian rivers do not naturally have the required depth and width throughout the year. This means that many interventions go into converting a river into a waterway. With the convergence of railways, roadways, and waterways for cargo movement, the environmental impacts of the Sahibganj MMT are the same as those produced by a port. So, the river’s approach channels need dredging for vessels to anchor, jetties need to be constructed, as well as trans-shipment terminals for the loading, unloading and storage of cargo. The fact that coal is the major cargo to be handled at the Sahibganj terminal is a greater cause for environmental concern.

Interventions such as levelling the ground, cutting trees, changing overall land use patterns, and actual construction activities for building the terminal are non-negotiable when it comes to building an MMT. Yet, they all lead to changes in the river’s hydrology and morphology. Such activities impact the livelihoods of fishers living here, while added noise pollution especially affects aquatic ecosystems, as do lights used for river navigation.

For example, “the terminal site is agricultural land at present with land cover consisting of crops, mango orchards and [sic] few settlements,” states the Environment Management Plan for Sahibganj MMT produced by IWAI. “Site is highly undulating with ground-level difference ranging from 30-56 m. Large quantity of cut & fill is required to achieve a flat surface,” it adds.

Divakar Yadav was distressed about the cruel manner in which many fruit-bearing mango trees were felled for the construction of the Sahibganj MMT. Compensatory afforestation completed in and around the terminal has hardly flourished. “The grass around the samplings is growing at a much faster pace than the saplings planted under compensatory afforestation,” he complained.

According to the Detailed Project Report, the main cargoes that will be handled at the Sahibganj Multimodal Terminal are coal and stone chips. The loading, unloading, storage, and transport of dirty cargo—such as coal—could potentially impact the surrounding environment, including the aquatic ecosystem of the river the MMT is located on. Ganges Dolphins, which are an endangered species, are also present in this stretch of the river. Recent research suggests significant impacts on their metabolic activity due to the movement of large barges.

All these impacts suggest that a prior Environment and Social Impact Assessment is warranted for an MMT of this scale.

As mandated by the World Bank, an Environment Management Plan (EMP) for Sahibganj MMT and an EMP for maintenance dredging was prepared by consultants (namely EQMS, in a joint venture with IRG Systems South Asia Pvt. Ltd. and Abnaki Infrastructure Applications & Integrated Development Pvt. Ltd) for the IWAI. The problem with such EMPs is the lack of scientific rigour and third-party monitoring in the process.

In this case, the Sahibganj MMT EMP was prepared for IWAI, but the process was also supervised by the IWAI. Yet the World Bank’s EMP guidelines may have been the only silver lining for this project—as they at least considered the need for assessment. On its own steam, the Ministry of Shipping gradually facilitated the circumvention of the legally binding Environment Clearance procedure for the inland waterways, especially the Jal Marg Vikas Project.

◯◯◯

In the Environment Impact Assessment Notification, 2006 (EIA), the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) lists the projects and activities which require Environment Clearance prior to commencing construction and operations. Although ‘inland waterways and riverine terminals’ are not included in the EIA Notification 2006, over various amendments, processes like dredging and port building have been mentioned. As discussed earlier, these are critical activities undertaken to build MMTs.

Yet, RTI documents accessed by Manthan Adhyayan Kendra, Pune, an independent research and advocacy centre on Water and Energy-related issues in India, show that the MoEFCC had clear opinions on whether Environment Clearances were applicable for riverine multimodal terminals.

In 2016, following a difference of opinion on the matter between the Ministry of Shipping and the MoEFCC, the Ministry of Law and Justice sought clarification from the MoEFCC on whether Environment Clearances were needed for the Varanasi MMT under the JMVP. In response, the MoEFCC specified that the “terminal is a part of the port and is covered under item 7(e) of the EIA Notification as amended”.

However, the Ministry of Law and Justice was not satisfied with the MoEFCC’s response as it did not specify the law which places multimodal terminals in the category of ports. The matter was then decided based on information from the Ministry of Shipping, which stated that the terminal does not fall under the category of ports.

This is a clear case of conflict of interest, as the Jal Marg Vikas Project is a project being developed by IWAI, which comes under the Ministry of Shipping. These contradictions continued in the years that followed.

Documents accessed by Manthan Adhyayan Kendra reveal that concerns over the applicability of Environment Clearances for inland waterways were also discussed in May 2017 by an MoEFCC-appointed Expert Committee. It recommended amending the EIA Notification, 2006, to include “inland waterways, jetties, and multimodal terminals under the list of items requiring prior Environmental Clearance.”

However, the Committee’s recommendations were never realised. In fact, in an Office Memorandum dated 21 December 2017, the MoEFCC went against its own Expert Committee’s comments to exempt the maintenance dredging component of constructing inland waterways from Environmental Clearances, subject to a list of safeguard conditions. This caveat is now being extended by the IWAI to exempt MMTs and jetties in the JMVP from environmental clearances altogether. Current policy deliberations on the matter seem unlikely to challenge this status quo.

◯◯◯

In the Draft EIA Notification 2020, the MoEFCC has placed all inland waterways projects in the B2 Category. This means that if the draft EIA Notification is finalised as it is, inland waterways projects will not require Environment Impact Assessments, appraisals by the appointed Expert Appraisal Committee, or public hearings on its undertakings. Since 2015, a case in the National Green Tribunal (NGT) has been deliberating the applicability of the EIA Notification, 2006, for the Jal Marg Vikas Project.

In an order dated 10 January 2020, the NGT directed the MoEFCC to constitute an Expert Committee composed of ecological and aquatic ecosystem experts to look into the matter. They were tasked to submit a report in three months. Then, on 16 December 2020, after many postponed hearings, the NGT reminded the MoEFCC to submit its report. A year and a half after its initial direction, on 2 September 2021, the NGT once again noted that the MoEFCC had still not furnished the information; soon after, the Tribunal was informed that the matter was now under the purview of the Ministry of Jal Shakti.

After three more adjournments, with the latest dated 24 January 2022, a submission by the MoEFCC or Ministry of Jal Shakti is yet to be made. The case remains adjourned till 7 March 2022.

All this while, the development of the Jal Marg Vikas Project continues, with the project on track for completion by December of 2023. In the absence of critical and independent scrutiny as well as legally binding Environment Clearances, the overall quality of environment and health of the local population, including those directly dependent on the river’s resources, remains at stake.

◯◯◯

Ultimately, we must ask whether interventions such as Multimodal Terminals and the legal gymnastics that protect them actually serve public interests. Looking at traditional waterborne commerce provides some answers.

A stretch of the Ganga Waterway from Rajmahal—a subdivision of Sahibganj where the MMT is located—to Manihari in Bihar is often plied by roll-on/roll-off (or ro-ro) ship that transport stone chips. This movement benefits small stone chips mining industries in Jharkhand and Bihar.

“The movement [of cargo] was already taking place on the river Ganga between Sahibganj and Manihari. The establishment of the Sahibganj MMT has nothing to do with this movement. In fact, we have lost three community ghats [embankments] where this terminal is built. The displaced people need better community ghats where they can bathe properly that are separate for women and men. They need access to the river for their animals”, says Divakar Yadav at the end of our call.

Between 2016 and early 2020, advocacy around India’s National Waterways programmes focussed on the promise of inland waterways as a game-changer with big barges and huge multimodal terminals. In 2020, however, there was a realistic softening in the government’s stance, with the revelation that only 25 out of 111 National Waterways are commercially viable for cargo and passenger transport. In 2020, the Prime Minister’s Office announced that the JMVP would be re-engineered to “correct imbalances” via project Arth Ganga, which would focus on catering to local communities along the river Ganga. This is a welcome step in the right direction.

However, there is also an emerging push to develop and increase the capacity of inland waterways in other directions. These plans are reflected in the policy documents such as the Maritime Vision 2030 wherein multimodal connectivity with inland waterways as well as cruise and seaplane initiatives are proposed. With these emerging new modes of transport on the cards, it is even more important to rethink the long-term environmental, social, and financial sustainability of these grand waterways projects.

Featured image of PM inaugurating the Sahibganj Multimodal terminal on September 12 2019 from PIB/Photogallery

[…] instance, in the case of India’s inland waterways where multimodal terminals are built, there are financial, social and environmental standards that […]

Ms Avliji.

Your detailed report on 3 ports MMTs

is indeed an eye opener of many glaring events needing immediate attention.

If India needs to progress, PMO has to act decisively on the glaring bad happenings.

Can we not reverse the scene happening Nepal and Bangladesh assists us to accept our exports and we accept their imports ..just thinking loud..

We need to act.. can not have suffering on account ESG..

Let us apply corrections soon.

Well wishes.

Prof Ajit Seshadri

The Vigyan Vijay Foundation

New Delhi