Written & Photographed by Vaishnavi Rathore

Udaipur, Western Rajasthan: Gajinder Kalal stood on a cliff in the Aravalli hill range facing the flatlands of Marwar, a region that is a part of the Thar Desert in western Rajasthan. The hill he stood on lies in Gogunda, Udaipur, located in southern Rajasthan’s Mewar area.

The views on either side of the cliff were contrasting: Ahead of Kalal lay the beginnings of the arid desert, and behind, green forests and trees laden with custard apples. The Aravallis are a barrier to the desert and they prevent the sands of the Thar from entering Mewar and beyond.

Kalal belongs to Jhadol, Gogunda’s neighbouring block, and was on his way to meet Hansa Ram, the former sarpanch (village head) of Karech. “This used to earlier be dry and barely anything grew here,” he said, crossing a pasture which forms a few hectares of the 359-hectare sprawl that has been restored by local communities.

Almost 17 years ago, the residents of Karech noticed a decline in the local tree cover and availability of fodder caused by the overuse of pastures and tree felling for fresh and dry wood. Through collective campaigns aligned with the government’s Joint Forest Management programme, since 2002 the community has successfully restored more than 300 hectares of common land.

Strict rules were laid down and adhered to by common consent-young saplings would not be grazed or cut, so the common grounds would remain closed for certain periods of the year; only dry, deadwood could be collected and not green, live trees, and so on.

Worldwide, over 1.3 billion people are living on degraded agricultural lands, according to a 2019 report tabled at the 14th Conference of Parties to the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD). These vulnerable populations also lack secure access to land and control over land resources.

In India, 96.54 million hectares, or 30% of the country’s total land area, is undergoing desertification, as per data collected in 2011-13 and cited in a 2018 report by The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI), a not-for-profit research body. Upto 10% of this degradation is caused by water erosion and loss of vegetation. Other factors are wind erosion, salinity and human causes. At 50% of its land area, Rajasthan is among six Indian states that face acute degradation, as per the TERI report.

The UN report recommended the prioritisation of land restoration and sustainable management measures in the most fragile areas of a country and for communities affected by desertification, land degradation and droughts in order to reduce the risk of forced migration.

Though they have little awareness of the UN recommendations, Hansa Ram and others have been working with precisely this strategy. After a month-long investigative journey in the Aravallis, it became clear that the region was struggling with the fallout of mining, construction, encroachment, and waste disposal. Community efforts like those undertaken in Karech could stem the tide of land degradation caused by these factors.

“If you look at it, these efforts by the communities are contributing towards preventing climate change,” said Chetan Dubey, team leader of Gogunda block who works with the Foundation for Ecological Security (FES), a not-for-profit working across seven states, including Rajasthan. “The heavy definitions and terms of climate change may not fit into their dictionary, but this collective effort at micro levels is combating climate change.”

Livelihoods and commons

Hansa Ram’s house stood in the middle of recently harvested maize fields. His is one of the 600 agricultural households in Karech, most of which are growing soya beans, wheat, and mustard amongst other crops. On Hansa Ram’s terrace, amla (gooseberries) and red chillies lay drying in the sun.

“These are from our homes but a lot of it also grows in the commons that we have restored,” said the farmer who is a leader of Van Suraksha aur Prabandhan Samiti (forest protection and management committee). This group was formed with the assistance of the FES.

Most households in the village depend on these common property resources for fruits, fodder, and timber.

In 2002, when the villagers observed a decline in local green cover, they organised themselves into the samiti. “Initially, people used to get irritated at the fact that a series of meetings would take place but no work would begin,” said Hansa Ram. “But it was these initial meetings that got us streamlined into a common thinking process.”

The samiti needed funds, and for that they needed to open a bank account. The minimum sum for a new account is Rs 500, and each household contributed around Rs 3. Now, the work could begin.

Working with the Joint Forest Management programme-a government initiative to involve local communities in the management of forests-the communities began the restoration process. The village discussed and made plans for conservation, incorporating decisions on zoning, the water requirement of saplings, and the species of saplings to be planted. “Today, the forest is so dense that it is difficult for two people to walk together, side by side,” said Hansa Ram.

How they did it

Once the first phase of planning was finalised, the focus turned to the management of the commons, and the formulation and implementation of strict rules in this regard. For instance, when the saplings are young, the common grounds had to remain closed to prevent the cattle from grazing, and villagers from collecting twigs and branches for firewood.

Today, of the total 359 hectares of land restored, only nine remain open throughout the year for grazing and collection of produce. The rest is kept protected for most of the year, and thrown open only in April and May when the grass in the commons is cut to prevent summer fires. When communities enter the commons to gather cattle fodder, another rule is followed—ek ghar se ek datli which means only one member of every household can collect fodder to prevent overuse.

There was one challenge that emerged during the management of the commons-maintenance and vigilance. “We have had instances where families were caught cutting trees for wood to build their houses,” said Hansa Ram. “This is despite the rule that only dry, deadwood can be collected and not green, live trees. Those families were then charged heavy fines.”

Further, if a villager is found grazing cattle during the months when the pastureland is kept closed, a fine is imposed. The fee depends on the animal in question-Rs 50 for goats, and Rs 10 for cows and buffaloes.

So how have the communities managed to ensure non-stop vigil? One system put in place for four years was the “lathi system” under which every family took on the responsibility one-by-one. But the system weakened soon after, with people prioritising other work. With that, the samiti collectively decided to employ a guard, and this annually cost each household Rs 750.

Over the years, the community even built a boundary wall along the restored lands using funds from the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), a scheme that provides 100 days of unskilled, wage employment in a year, in rural India. Discussions are now on to plant more custard apple trees, bamboo and other plants along the boundary wall. The idea is to create a permanent, green “wall”.

When we visited the village, around 25 residents had gathered at the gram panchayat building to discuss the possibility of creating a cooperative to sell custard apples. This could help them negotiate better prices for the produce and remove middlemen. Karech’s residents were set to once again wield their weapon—collective and sustainable decision-making and action.

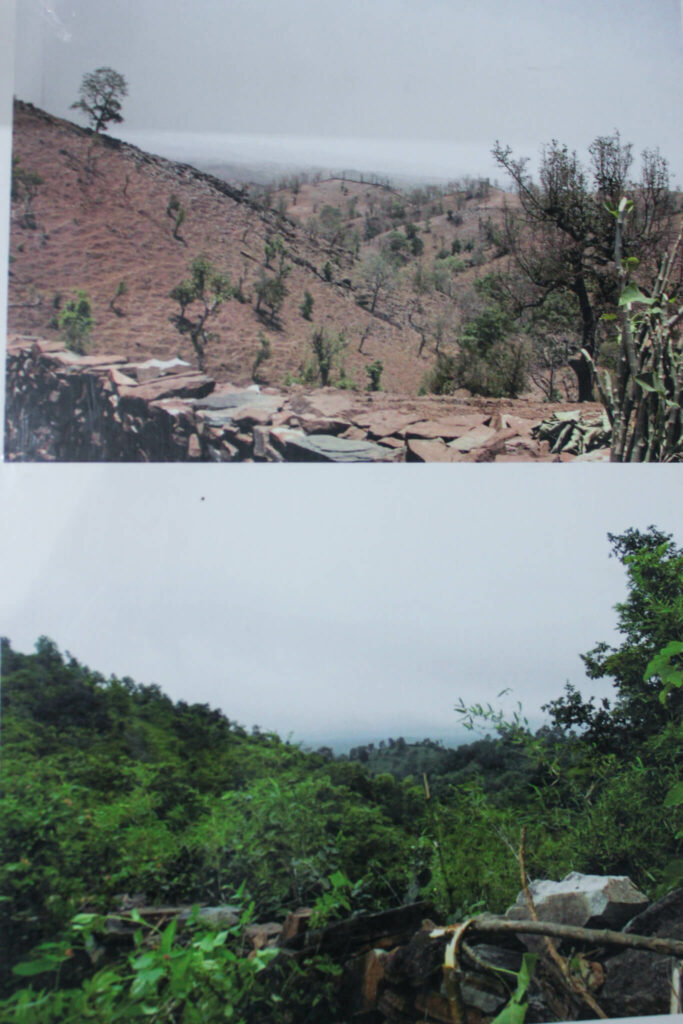

The change and improvement is dramatic in just 3 years, as the photos reveal. The only way to protect our common property resources is the involvement and ownership of the local community facilitated by a change agent. This story validates such an approach, again. Good work, Bastion and Vaishnavi. All the best

Excellent work Vaishnavi . Your hard work and the interest you have taken in this field should encourage others to follow.

Outstanding work Vaishnavi we need to highlight these grassroot revivals for the rest of us to see