Written by Sourya Reddy

Updated on 09/09/18

Sumaira Abdulali, one of India’s foremost campaigners against illegal sand mining, revealed in a documentary how she was physically attacked when she was trying to stop a truck illicitly carrying sand. The attack left her right hand paralysed. In April earlier this year, two women police officers were assaulted by a group of sand miners during a raid in Udupi. Those who oppose the ‘sand mafia’ and illegal trade of sand often face such hostilities.

In India, illegal sand mining activities generate an estimated $16 million to $17 million a month. The nexus is an extremely complicated one; it is one that entangles miners, government officials and local communities (who derive a decent livelihood from mining). This problem has no easy answers, and to worsen matters, the absence of exact and reliable data on sand mining greatly contributes to the lack of knowledge on the environmental damage it causes.

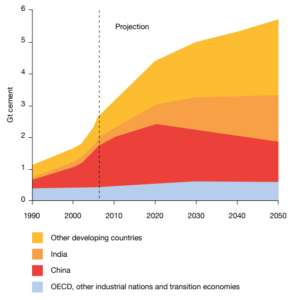

Over the last two decades, production of cement has multiplied nearly three-fold, from around 1.4 billion tonnes in 1994 to 3.7 billion tonnes in 2012

The United Nations estimates that illegal sand mining could threaten the existence of over 70% of the world’s beaches. To truly understand the problem of sand mining in the Indian context, we must begin by understanding why sand is being mined to the extent that it is.

Sand is an extremely important resource, especially in the fast urbanizing world. It is an indispensable ingredient in the plaster and concrete industries. Sand in river channels, beaches and floodplains are mined to make these items. It is also added to clays to help reduce shrinkage and cracking during manufacture of bricks.

Since they are the main ingredients in concrete, sand and gravel are mined more than any other material, but reliable data on their extraction is not available. This makes an assessment of its sustainability difficult and contributes to the lack of awareness on the topic.

One way to estimate the global use and extraction of sand is to measure cement production for concrete. The share of the urban population globally has risen from just under 34% in 1960 to a little over 54% in 2016. This massive expansion has consequently increased the demand for cement, and hence, sand.

In the last two decades, for instance, production of cement has multiplied nearly three-fold, from around 1.4 billion tonnes in 1994 to over 3 billion tonnes in 2012. Asia’s rapid economic growth has been a major contributor. In India alone, the annual use of construction sand has more than trebled since 2000 and is still sky-rocketing.

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) in 2013 estimated that for each tonne of cement, the building industry requires around six to seven additional tonnes of gravel and sand. Back of the envelope calculations show that the global use of sand, therefore, would be almost 26 billion tonnes in 2012 alone. If we take into account other uses of sand such as land reclamation, road embankments, shoreline developments (for which global statistics as of now are unavailable), asphalt pavements and concrete roads, this estimate would shoot up to 40 billion tonnes a year!

The Indian Problem

Sand is a ‘minor mineral’, as defined in section 3(e) of the Mines and Minerals Development and Regulation Act of 1957 (coal and iron are the major minerals). The law empowers state governments to form rules on mining leases of minor minerals and to prevent illegal mining of any minerals.

In 2015, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change released the Sustainable Sand Mining Management Guidelines Report, which lists several deleterious effects of the activity. The points include:

- Excess extraction of river bed material causes the bed to degrade and leads to downstream erosion.

- In-stream habitat gets impacted, due to an increase in the river gradient and sediment deposition. Excessive sediment deposition is particularly dangerous, as it increases turbidity, which prevents the penetration of light required for photosynthesis. It also reduces the food availability for aquatic fauna.

- Bed degradation can cause the loss of properties, and damage to the landscape, to the extent that it can undermine bridge supports, pipelines and other structures.

- Lowering of the groundwater table in the floodplains.

These are just five of the nineteen mentioned harmful effects in the report. A 2007 study by D. Padmalal et al, on the impact of river sand mining in the river catchments of Vembanad lake in Kerala, found that the degradation of the rivers that drain the lake is severe, especially those in the alluvial regions, and “the riverbed in the storage zone has been getting lowered at a rate of 7-15 cm per year over the past two decades”.

Various governments and the judiciary have taken steps to ensure sustainable mining and reduce illegal mining as much as possible. For example, on May 22 earlier this year, the Madhya Pradesh government imposed a ban on sand mining on the riverbed of the Narmada, a river that is said to be the lifeline of the state. It also formed a committee of experts to suggest methods to prevent ecological damage to the state.

Andhra Pradesh is likely to see a spike in sand mining soon due to the construction of its new capital city Amaravati

The state, which already had strict mining regulations, now intends to cut middlemen out by providing free sand from existing quarries to consumers (who have to then just pay for the transportation costs). This policy, launched last year, also aims to regulate sand prices, increase monitoring and promote innovations in construction techniques which require less use of natural sand.

However, the impact of the steps remains to be seen. The Supreme Court had in 2012 ruled that all sand mining and gravel collection activities required mandatory approval under the Environment Impact Assessment (2006) notification. In May of the same year, the Ministry of Environment issued an order in tandem with the ruling, saying that permissions had to be sought for all mining activities.

Despite this, in Himachal Pradesh alone, approximately 8,500 cases of illegal mining were reported in the last financial year and a fine of Rs. 4.5 crore was levied on the arrested. The year before, 9,300 cases were reported.

The urban boom has spawned illegal sand mining; and, despite regulations and growing activism, illegal mining persists and is an ominous enemy to India’s ecological well-being. There have been several instances wherein journalists, government officials and activists such as Abdulali have been intimidated and violently silenced.

At the rate it is being carried out around the world, sand mining is unsustainable and brings with it deadly environmental and ecological costs. Innovation in the construction industry (so as to reduce dependence on natural sand) coupled with stricter and more effective government regulation is necessary to beat what is an avoidable human-made calamity.

This article is the first in a two-part feature on sand mining. Featured Photo by Prashant, CC BY-SA 2.0