The Right to Education Act of 2009 constitutionally grants every child between the ages of 6 and 14 with a right to avail free education. Last year, the Draft National Education Policy had a special focus on inclusive education, besides major structural reforms in education policy. Yet, there are sections of children between 6 and 14 years of age who also miss out on quality education, like children in conflict with the law.

While the jury is still out on whether there is a universal notion of ‘childhood’, most Indian laws such as the Juvenile Justice Act of 2015 and the POCSO Act of 2012 define a child as a person below 18 years of age. A child who is guilty of committing a crime gets sent to a juvenile observation home, which is a facility (run by state governments or voluntary organisations) that is approved and certified by the state government.

“I will get married to my girlfriend after getting out of the home. Her parents know about me… they like me as well!” says 16-year-old Prateek when I ask whether he plans to enter school after leaving his observation home in Gujarat. Prateek was acquitted for murdering a young boy out of revenge. His family barely managed to make ends meet and could never send him to a school. He finds himself among at least 31,000 other children who committed crimes in 2018 that ranged from theft to rapes and murders.

According to the 1985 Beijing Rules, the role of observation homes is to provide the care, protection, education and vocational skills required to facilitate a child’s reformation into society. How well equipped are observation homes to offer educational interventions and enable these delinquent children’s aspirations for the future?

What do you teach a delinquent child?

15-year olds Hari and Aditya were arrested for being in a fight on the streets of Vadodara. They were let out of the observation home within 48 hours. On the other hand, Prateek has been in there for almost a year now. Curating educational interventions for juveniles becomes difficult because there is no surety of how long a child will spend in the home.

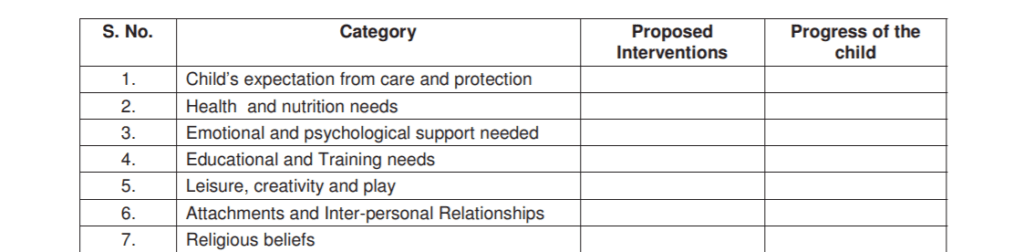

In such a situation, one option would be to strictly follow an ‘Individual Care Plan’. These are comprehensive plans for the child listed in Form 7; it is to be followed in the interest of reforming a child holistically. It highlights what the child would need in terms of psychological and educational help, amongst others:

Some boys come to me and cry, some say they regret what they have done. I think what they need is another chance. Better education and awareness can make them like any regular child with dreams and aspirations that align with that of society

- Alpa, a teacher at the observation home

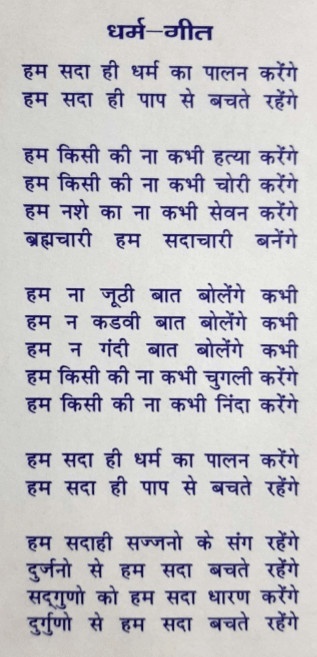

With most of these children not having any formal schooling background, it becomes challenging to design a curriculum that includes subjects like science, math, and social sciences. A curriculum that focuses more on the pragmatic aspects of life, and on nurturing moral and ethical values seems more pragmatic. Several NGOs have intervened in juvenile homes by introducing meditation and spiritual healing sessions. These are aimed at instigating a child’s self-reflection about their actions.

In an educational intervention in American prison homes, inmates were taught empathy and responsibility by taking them to animal shelters and homes of the elderly. They were made to serve there; such a mode of learning has no start or end point per se and it would fit well within the mandated Individual Care Plan.

Peer Interactions: The Role of “Reputation”

The children’s schedule in this observation home seems structured, but it isn’t goal-oriented or productive. They indulge in daily chores like cooking, cleaning and washing utensils. They study for almost 3 hours every day despite the fact that not all of them know how to read and write. Despite all this, they seem to have lots of time to be with each other.

We are surrounded by hierarchies in our social lives, from our living room to our offices. This is naturally emulated even in the home. Living in one big room with no bifurcation between each others’ space has fostered a sense of hierarchy, pride and reputation amongst the children.

This hierarchy is based on the nature and degree of their crimes. So, since Prateek came in on charges of murder while Aditya had just been in a fist-fight, Prateek would feel more entitled to exercise control over Aditya and the others. It seemed normalised — after all, Prateek had indeed committed a crime that required much more ‘strength’ and ‘bravery’ than the others’ crimes.

Consequently, the aspirations of children in these homes are shaped by their interactions with their peers. At this age, they are susceptible to being led further astray. So much so, that such interactions can actually motivate them to commit more heinous crimes in the future as well. Using a well-detailed curriculum, one way to reduce the influence of ‘reputation’ amongst the children is to paint a positive image of their future. Authorities must help them internalize why they want to be a better member of their societies.

A more effective way to curb dangerous peer influence could be to segregate the children based on the nature of their crimes. However, since this method of physical separation would isolate a certain group of delinquents, one would need to also keep them psychologically and mentally healthy.

Specialised Teaching Required

Under the RTE Act of 2009, it is compulsory for teachers to have a Bachelor of Education degree. However, that degree alone will do little to handle juveniles because observation homes are not like any regular school.

One thing that remains constant in almost all cases is that these children belong to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes; which means they have minimal access to resources like good food or formal education. Eventually, they lose interest and drop out of schools. As a result of this deprivation, they indulge in activities and end up in observation homes

- A government officer (Samaj Suraksha Adhikari) responsible for this observation home

In a report by the NCPCR, it was suggested that observation homes be linked with Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan for better educational outcomes. However, during our stint studying this home in Gujarat, we found the SSA-recruited teacher rudely call out to children, asking them what crimes they had committed while being introduced to us. It might not have been intentional, but such comments leave indelible scars on children who are already deemed to be outlaws by their society.

The teachers and administrative staff who deal directly with such children require specialised training. Frequent follow-ups and class observations will help keep a check on the way things are taught in these homes. Besides following the prescribed curriculum and reducing peer influence, the teacher is pivotal because they spend the most time with these children. We need to start looking at them as human beings that can be reformed with care, as Mrs Kamal Gaur, deputy programme director for education at Save the Children India tells me,

Children between the ages of 11-14, 14-16 and 16-18 all have specific requirements for care. The language and social skills imbibed from the learning environment must be similar to what a child gets from their family: both physically and psychologically. Who else can these children go to?

The only thing that these children know for sure is that as soon as they step outside, the world will not look at them in the same way. Perhaps they will never be able to fulfil their dreams. However, what we can ensure is an equal opportunity for them to learn as individuals and grow into responsible adults. What we can do is promote their dignity and self-worth within these homes, and provide them with the tools to shape their futures for the better.

Editor’s Note: This study was conducted in one observation home in a city in Gujarat, as part of a project by IIM Ahmedabad’s Winter School in 2019. It does not intend on making blanket claims on the state of observation homes across the country.

Names have been changed to protect the identity of these children.