This article is the first in our two-part series on how Pragat Shaikshanik Maharashtra, an education reform policy, was implemented to improve learning outcomes of children and the working conditions of the cadre who are responsible for policy implementation.

Most of us have heard of the Government’s education programmes such as the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan or the Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao. From newspaper and TV advertisements to celebrity and door-to-door campaigns, the government goes out of its way to highlight such flagship programmes that aim to reform the state of education in India.

While some education policies ring loud across the nation, we rarely hear educational interventions at the state level. One such policy is the Maharashtra government’s Pragat Shaikshanik Maharashtra (PSM), which intends on improving Foundational Literacy and Numeracy (FLN) for children aged 6-14 years in all schools across the state. PSM, which loosely translates to Progressive Learning Maharashtra, was introduced in June 2015. It aimed to ensure that every child became proficient in reading, writing, and arithmetical concepts, appropriate for their age.

The success of the PSM has largely been attributed to its teachers and its ability to include digital technology and school infrastructure development, besides getting ISO marks for schools. During an interview with ABP Majha, Vinod Tawde, the former Minister of School Education, Higher and Technical Education for Maharashtra also had similar views to share. “Our teachers are the reason for the success of Pragat Shaikshanik Maharashtra,” Tawde said.

Teachers are certainly key to the PSM’s success, but what most of us do not know is the behind the scenes. How are the various schemes and policies meant for the education sector conceived? How are the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan or the Beti Bachao programmes implemented on the ground? At the heart of making these policies come to life are people who ensure that large scale reforms in the education sector become a reality.

Turning any policy into a reality, by literally taking it from paper to participant, requires dedicated effort from all management levels—top level, middle level and ground level. Today the PSM rests on shaky grounds given the change in governments and their shifting priorities. People working on ground speculate that this policy has been discontinued or perhaps starving for financial support. However, the PSM serves as a good blueprint to understand how the management in the middle who are implementing policies are the catalysts of change.

The Brokers in the Middle

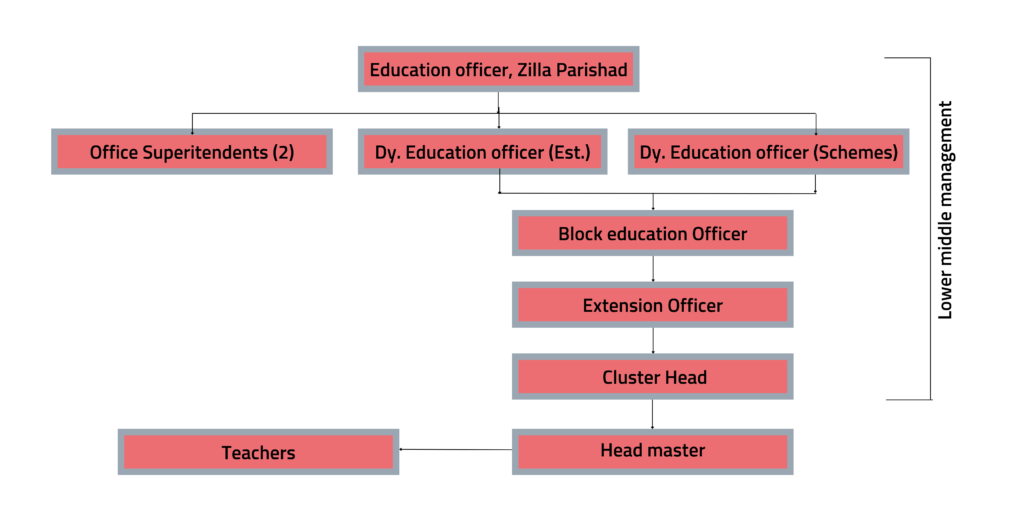

In governance, the middle management comprises directors, deputy directors, block officers and so on. The middle management in the education department, however, differs. Here, the middle manager’s position lies between the deputy secretaries operating at the top level, and school headmasters at the ground level. The middle management is further classified in two categories—upper-middle management and lower-middle management.

While the upper middle management level ranges from directors and administrative officers for various departments to education officers at the district level, the lower-middle management includes officers—deputy education officers, office superintendents, block education officers, extension officers, and cluster heads. These officers are responsible for successfully implementing policies and constitutional or statutory provisions known as Government Resolutions (GRs). These are the people who work with the teachers who receive praise for successfully implementing programs like Maharashtra’s PSM.

Our focus here is to better understand the middle managers, in particular the lower-middle managers. While the role of top and ground-level management is regularly highlighted, the contributions made by those in the middle are usually overlooked. The middle managers are like brokers who perform the key function of communicating information and commands both upwards and downwards. Within middle managers, those at the lower end are often found to be especially burdened.

Middle managers are like the spine of the system that manages everything from top to bottom, acting as a connecting link between all levels.

—A Block Education Officer

The Invisibilised Men in the Middle

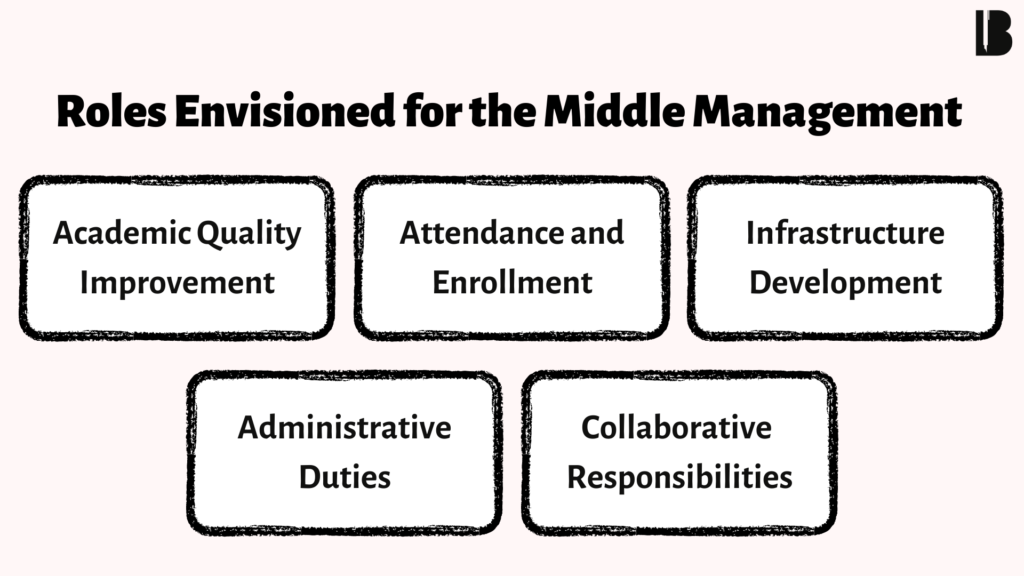

In 2018-19, Leadership for Equity (LFE), an organisation based in Pune, worked jointly with the Maharashtra Education Department to revise the roles and responsibilities of its cadre. However, the vision created as part of this joint effort has not been approved by the government for implementation yet. It is important to note that since 2002, the roles for middle managers have not been revised, which is dictated by Government Resolutions.

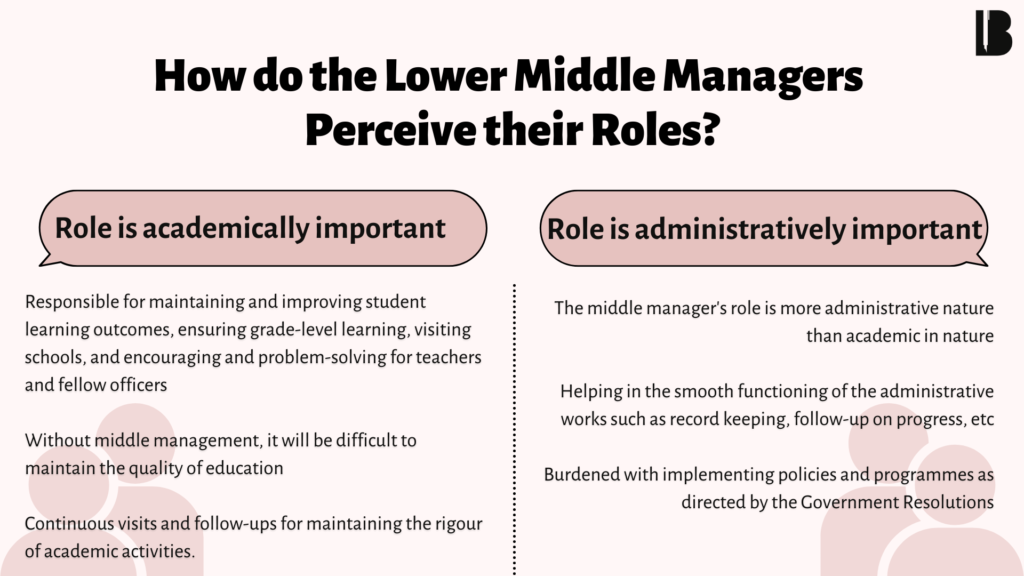

On a day-to-day basis, the lower-middle manager’s role differs and goes beyond the five categories mentioned above. Broadly, categories fall into two functions: academic and administrative. During LFE’s study in the first half of 2021, here’s what the lower-middle managers perceived their roles to be:

Understanding the role of lower-middle managers can be complex for the uninitiated. To simplify this, let us take a closer look at the Pragat Shaikshanik Maharashtra policy, which was examined by LFE for making observations on the challenges and expectations of lower-middle management. In order for the PSM to be successful, the policy needed to empower students as well as teachers. This meant that the role of lower-middle managers attained prime importance as nodes for giving directions regarding implementing policy, besides also being the primary source of contact on the ground for top officials.

The [PSM] policy majorly focused upon practising equality among all officers, [a revolution] popularised as ‘Saheb se Saathi’ [from a superior to a friend]. This made it easier to communicate problems, success stories and roadblocks ahead.

—A Lower-Middle Manager

Leadership for Equity conducted in-depth interviews with 25 officers in two phases from Ahmednagar, Chandrapur, Hingoli, Nagpur, Nanded, Nandurbar, Nashik, Osmanabad, Pune and Satara districts of Maharashtra. These field insights helped deconstruct the roles of the lower-middle managers during the PSM’s implementation. As a lower-middle manager said, “When I joined, there was a big confusion about our roles. This policy [PSM] helped us find more rigour in our role and laid a clear roadmap.”

Interviews with lower-middle managers reveal that the successful implementation of the policy was an outcome of multiple factors—clear strategic planning, demand-based training, recognition and trust among the levels, regular follow-ups of policy status, transparency, power and authority to ground staff, freedom to perform, and a bottom to top approach.

One specific specialty, different from the other policies, is that the PSM focused more on need-based training as per the demand put forward by officers, rather than unnecessary training.

—A Lower-Middle Manager

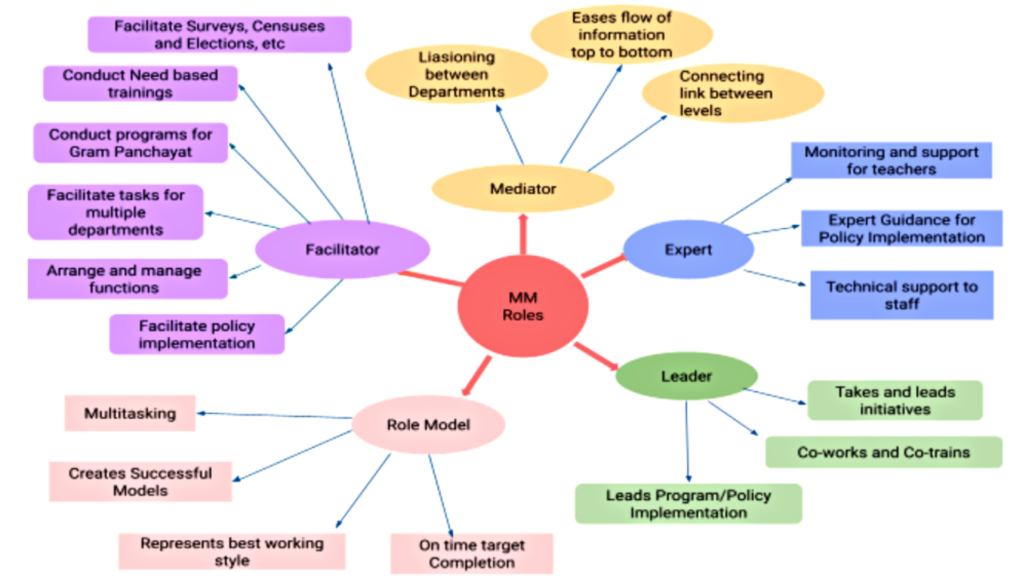

While implementing the PSM, middle managers’ roles observed a major shift. Their roles encompassed five main characteristics as facilitators, mediators, experts, leaders, and role models, defined in detail below.

According to news reports, nearly 60% of Maharashtra’s primary schools have been digitised, from 11,228 in 2015 to 63,458 in 2018. In 2018-19, 94,000 students in Maharashtra switched from private schools to Zilla Parishad Schools. These and many more stories of success have made headlines, but here’s what the lower-middle management wants us to know—as a school’s progress is indicative of the teachers’ success, when a cluster progresses, it is considered to be a joint effort of the teachers as well as the officers in charge of the given cluster. In the midst of all this, the entire middle management goes unseen, unheard, and unrecognised.

While the top officials defined the middle managers as mere connecting links between the different hierarchies, the middle management themselves see their role as the centre of the system. According to them, they are responsible for being the first point of contact for both levels—top and bottom.

Middle managers cannot only be called as only mediators but someone who can contribute more than just the job chart to the daily functioning.

—A Lower-Middle Manager

From Administration and Schools to Academics and Students

The Pragat Shaikshanik Maharashtra’s Government Resolution lays down clear guidelines for the middle managers to help with implementing policy. This included supporting teachers as mentors, ensuring that the PSM was implemented as per guidelines, and enabling the flow of information to teachers. Managers were also tasked with finding the level of competence among students in order to understand whether they possessed age-appropriate mathematical and language skills, were happy and confident, and if the atmosphere in their school was free and relaxed. Since its inception, the PSM has enjoyed success in many of these areas.

With these changes, the PSM ushered a new dawn in the role played by middle managers. Now, their role has gone from being viewed as an administrative one, to one that is concerned with academic leadership development such as teacher support and aligning with students’ learning goals.

Earlier, everyone was only concerned about the administrative part rather than the educational outcomes. Over time, slowly but steadily, this habit of follow-up had begun, but unfortunately the [PSM] policy was stopped.

—A Lower-Middle Manager

Unlike other educational policies, the PSM gave freedom to officers to perform and take initiative within limited expenses, as the policy prioritised empowering teachers rather than officers. The training pattern also changed as they were now demand-based and the same training was given to both the teachers and officers at the block and district level, which is a rare practice while implementing policy. The officers had clarity and direction to perform their duties while implementing the PSM, given the detailed description of roles in the Government Resolution.

The middle managers saw a change when compared to the older style of supervision. Our visits now became ‘mool bhet’ [student visit] instead of ‘shal bhet’ [school visit].

—A Lower-Middle Manager

Challenges of Being Stuck in the Middle

The extra burden of additional duties without any support from above, causes fatigue and lower productivity at the work front.

—A Lower-Middle Manager

The study revealed several challenges faced by the lower-middle managers. Vacant positions in different cadres add responsibilities to the officers’ plates. In some cases, the teams operated with only 50% or less staff. “There are so many vacancies that we, as Kendra Pramukhs (Cluster Heads), are overburdened. It feels like 40% of the staff is working for 100% of the positions [of responsibility],” sighs one of the lower-middle managers. Another one says that “there are a lot of posts yet to be filled… almost every department is functioning with minimum staff and extra workload. How can you expect us to perform well with this load?”

These are valid concerns for people entrusted with implementing policies that are aimed at creating a difference on the ground. Lower management officers also have to complete tasks for the upper management, which consumes most of their time. The pressure of time-bound projects along with extra work responsibilities results in poor output and an inability to complete what was originally entrusted upon them.

Earlier, school visits used to get over in less than 3 hours, but now even 3 hours has become less.

—A Lower-Middle Manager

Technology has a primary role in today’s government offices; many officers struggle with basic computer work like updating a sheet, keeping data records, etc. This is not a problem unique to the lower-middle managers alone. As one of the top officials says, “…many officers from the upper management lack the modern technical skills, as a result of which they have to request help from others.” However, the inclusion of technology has been beneficial in making work easier and less burdensome for some officers. For the others, there is scant support and training to enhance their skills. Officers also said that they have to invest extra time for training the clerks as per their requirement.

There is also the problem of insufficient infrastructure, right from an office to sit and work, to a computer or vehicle for the middle manager to make frequent visits. Not having a vehicle to travel to their destinations affected the frequency with which they could visit schools. Other issues of accessibility and poor network connectivity makes it difficult for officers to serve some regions with regular information and support.

We remain as [the right hand] to the Block Education Officer, yet our work gets less recognised.

– A Lower-Middle Manager on Additional Duty

While middle managers plan an important role in connecting the upper and lower levels, they often find themselves invisibilised by the nature of their responsibilities. In the process, middle managers’ workload increases to a degree that affects the implementation of education services in hard-to-access parts of India. While challenges abound in their work lives, many strategies and solutions exist to improve the way forward. Read Part Two to know more.

Featured image by Leadership for Equity (LFE) is of a Shikshan Parishad [monthly cluster meeting], a process institutionalised for discussing progress and capacity building of teachers in-service initiated by Kendra Pramukhs [Cluster Resource Persons] in Maharashtra.

I appreciate this excellent post and the valuable information it provides. It was truly enlightening, and your website is incredibly beneficial. Thank you for generously sharing!

[…] LEAD is a dedicated blended learning program for the professional development of officers in the middle management of the education […]

[…] Typically, the education department ecosystem consists of three layers: the top policy-making cadre, the middle management and the frontline service providers (teachers). The middle management position lies between the deputy secretaries operating at the top level, and school headmasters at the ground level. These officers are responsible for successfully implementing policies and constitutional or statutory provisions known as Government Resolutions (GRs). A detailed documentation of the hierarchy of officers to teachers has been published earlier on The Bastion by Sumana Acharya, Research Associate at Leadership for Equity. Read the article here. […]

[…] This article is the second in our two-part series on the middle managers who are responsible for implementing education reform policy in Maharashtra and how they navigate through challenges at their workplace by employing strategies and solutions. Click here to read part one. […]