Bamboo flowers and statehood are not terms that usually belong in the same sentence. But, when discussing Mizoram, they do. The sprouting of bamboo flowers happens only once every 50 years, yet, it sparks an intriguing chain of events—rats consume the flowers, increase in numbers, and then move on to feast upon the majority of standing crops in the region, creating a devastating food shortage. Locally known as mautam, some of these infamous periodic famines have been reported to take up to 15,000 Mizo lives. In 1959, a mautam occurred in Lushai Hills, which was then a district in undivided Assam. The events that transpired after it not only make Mizoram’s history, they also reveal the reasons behind the violent clashes on the Assam-Mizoram border in July of 2021.

To demand relief from the Centre during the extreme food shortage in 1959, the Mizo Cultural Society—who renamed themselves as the Mizo National Famine Front—came to the fore in 1960. They quickly became popular: members of the Front busied themselves in transporting rice and other essentials to the interior villages of the Lushai Hills. The very next year, the Front underwent a radical transformation—‘Famine’ was dropped from their name, and with this omission, their goals changed. The newly christened Mizo National Front demanded sovereignty over ‘Mizo’ territory and independence from Assam. In the decade that followed, the Front claimed responsibility for numerous violent activities across the region, and by 1979, they were outlawed by the Centre. But by then, the seeds of demanding an independent state of Mizoram had been sowed in the minds of the public. In 1972, Mizoram became a Union Territory, and fifteen years later in 1987, a state.

Like Mizoram, Meghalaya, Nagaland, and Arunachal Pradesh were also carved out of Assam. But, after the Centre demarcated their independent territories, the four states were left dissatisfied with losing their ‘rightful’ areas to Assam. Since their inception, this resentment has led to instances of violence between the four states and Assam—the most recent being this year’s episode in July, when firing broke out between Mizoram and Assam’s police forces stationed on the Assam-Mizoram border. Seven people died and 60 were injured. In fact, between 1972 and 2021, such clashes between Assam and the states portioned out of it have killed 157 people, injured 360, and displaced over 65,000.

Honble @ZoramthangaCM ji , Kolasib ( Mizoram) SP is asking us to withdraw from our post until then their civilians won’t listen nor stop violence. How can we run government in such circumstances? Hope you will intervene at earliest @AmitShah @PMOIndia pic.twitter.com/72CWWiJGf3

— Himanta Biswa Sarma (@himantabiswa) July 26, 2021

As contested as these borders are, at the heart of the clashes lie the lucrative resources that fall within the states’ borders, whose extraction are shaped by colonial history in Northeast India. In the case of the Mizo-Assam clash, the major bone of contention was a crucial resource—the Inner Line Reserve Forest, the largest of its kind in Assam.

A Forest of Contention

Bordering Mizoram on the south and east, the Inner Line Reserved Forest (IRLF) today sprawls over 1,318 square kilometres (sq km), of which almost 750 sq km fall in Assam’s Cachar district. Both Mizoram and Assam recognise different boundaries of the Reserved Forest, accusing the other of encroaching into ‘their’ areas. The June 2021 clashes were a culmination of decades of such accusations. The Mizoram government claimed that Assamese officials encroached upon and destroyed plantation crops in the state, while Assam accused Mizo residents of planting banana and betel nut saplings and constructing makeshift settlements in Assamese territory.

Assam on the other hand accepts a different boundary, described through a notification issued in 1933. In it, the British re-drew districts based on cultural, linguistic, and tribal lines, giving rise to new boundaries for Manipur, the Lushai Hills, and the Cachar plains. In doing so, some parts of the Lushai Hills went to Manipur, much to the dislike of tribal chiefs in Mizoram, who claimed that they had not been consulted in the process. So, when Mizoram was declared a state in 1987, its leaders stated that by backing the formation of new districts based on the 1933 notification, Assam had taken parts of Mizoram’s reserved forest away.

“This present scenario [of conflict] is not only a result of colonial extraction of natural resources. It is also reflective of the under-representation of Mizos in government machinery,” says TBC Lalvenchhunga, a politician from Mizoram and a party worker with the Zoram People’s Movement, in a personal capacity. “The British never allowed political parties to be formed in the Lushai Hills, and post-independence too, when the demarcations were happening, there was no representation of the Mizo community in these decisions.”

This lack of representation added to tensions amplified by other factors. “For communities living in these regions of Mizoram and Assam, imagined boundaries, a strong insider-outsider perception [between different tribes and ethnicities], and the assertion of ethnic identities strongly linked to their homeland’s boundaries also contributed to the violence that we see in recent times between Assam and the states carved out of it,” says Guwahati-based Sushanta Talukdar, Editor at NEZINE, a magazine focusing on Northeast India. “These issues hardened with the colonial history of resource extraction in the region.”

Talukdar is right. Viewing the demarcation through a historical lens shows that the origins of the Reserved Forest were triggered by a series of inter-tribal and tribal-British clashes.

A History of Extraction that Demanded a Reserved Forest

“Since pre-colonial times [the 19th century], the tribes living in the Cachar plains in Assam were frequently raided by tribes living in the Lushai Hills [which today are in Mizoram, but were then a part of undivided Assam]. Such raids and clashes between tribes were a way of showing one’s own clan that they had control over the ‘other’ tribe, and that they would provide for and protect their own community against them,” says Dr. Pushpita Das, Research Fellow at the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses. Integral to the local culture, these raids by tribes like the Lushai and Kukis were often violent, resulting in the plunder of surplus resources, and in some cases, the kidnapping or murder of those identified as enemies.

To phase these clashes out, in the 17th century the Ahom King Pratap Singha (1603-1641 BCE) introduced the ‘posa’ system, through which tribes residing in the plains paid commodities or cash to the hill tribes to not raid them. When Assam came under the colonial administration in 1838, which included swathes of the Ahom kingdom, the British continued with the posa system, paying the hill tribes commodities instead.

Yet, the clashes continued. This had much to do with the colonial exploration of natural resources in the region and eventual control over them—rubber and tea plantations became a favoured British business to nurture. These growing industries, especially tea plantations, felled trees and encroached upon the Lushai tribes’ lands and traditional hunting grounds, threatening their historical socio-cultural ties with forests. Bamboo, for instance, featured heavily in Lushai culture—it was used in the walls, roofs, and floors of their houses, to make traditional ornaments and headgear, and in food, and dances. Streams and rivers were components of Lushai folk tales and songs too, highlighting their cultural ties to the surrounding environment.

The growth of the tea and rubber business in the latter half of the 19th century, was accompanied by a steady inflow of foreigners to the Lushai Hills and Cachai Plains which led to “grievances in the minds of the tribes that culminated in tribal attacks,” writes researcher Srijani Bhattacharjee in her 2020 paper. Perhaps the final straw for the colonial authorities was the murder of a British tea planter and the kidnapping of his daughter, as Bhattacharjee writes in her paper. The event sparked a realisation for the British: these industries could prosper only if peace with the tribes was brokered.

This is what led to the adoption of the ‘Inner Line’ under the 1873 notification. The permissions it demanded to enter parts of undivided Assam became a way to limit the inflow of ‘outsiders’ and diffuse the tribal-British clashes. The British realised that the forest could be a natural buffer between the Lushai Hills and the Cachar plains, and in 1877, demarcated it as a reserved forest to avert the raids where the plantations were located. All of this was done in a bid to nurture what the British held as a priority—the growth of the rubber and tea industries.

While the colonial government saw this manoeuvre as a way to diminish raids and violence, today, the forests are important to both Mizoram and Assam for the resources they provide to both states.

The Wealth of the Forest

“As much as land is important to the states who are contesting ownership of these areas, it is also the forest and its resources that are valuable in this region, where there are only a few livelihood options available,” says Das. The Inner Line Reserve Forest is dense with deciduous and evergreen forests laden with monkey fruit (Artocarpus lakoocha), mangoes, elephant apple (Dillenia indica), bamboo, and cane. Rich biodiversity thrives here with various species of monkeys, jungle cats, deer, pangolins, including the endangered Hoolock Gibbon residing in the foliage.

The timber and non-timber forest produce available here are important livelihood sources for the communities living in the 24 forest villages within this reserved forest. A 2010 study of 654 households within the forest found that 72% of households were dependent on non-timber forest produce for their livelihoods, alongside their primary occupations as agriculturalists, betel leaf cultivators, or workers on tea plantations. “For many communities in Mizoram and even in Nagaland, forests are also avenues for fishing and hunting. Mizoram has also been demanding [jurisdiction over] this area since jhum [shifting cultivation which involves clearing land by burning, cultivating it for a limited time, and then abandoning it for regeneration] is practised along the fringes of the ILRF, although in the last few years jhum has also reduced,” Das adds.

Undoubtedly, the wealth of these forests are of importance to both the contesting states. But they are not alone. Other states have made their voices heard about losing their ‘rightful’ forests and other natural resources to Assam. Nagaland demands 12,488 sq km of Assamese territory, which comprise 10 Reserve Forests, while Arunachal Pradesh claims that over 3600 sq km of plain areas were transferred to Assam in 1951, without the consent of its own people. Meghalaya has demanded two blocks of the Mikir hills in Assam, which they assert previously belonged to Meghalaya’s Jaintia and Khasi Hills. These demands have been raised through various agreements with the Union government as well. For instance, points 12 and 13 of a 16-Point Agreement signed between the Naga People’s Convention and the Centre in 1960 demanded a “Consolidation of Forest Areas” and “Consolidation of Contiguous Naga Areas”—which simply ask for a “transfer of areas from one state to another.”

Negotiations and talks have been active via the formation of regional committees, the latest announced by Mizoram in early September this year, and between Meghalaya and Assam in August. Assam has even filed cases against the opposing states at various points in time for encroaching on their territory, leading to formations of various committees to investigate the matters. Some of the cases are pending.

But, moving towards peaceful borders and better-shared resources is easier said than done. “These issues of reclaiming forests and lands were also a part of insurgency movements in the Northeast. It then becomes difficult to segregate them from local politics and violence,” shares Das. “Local politicians often use these to rally and gain popularity, but instead of these divisive policies, they should talk about inclusiveness. The solution to these conflicts depends heavily on political will.”

Talukdar offers another conflict resolution method, one that is integrated with the communities’ everyday lives. “Communities living on either side of the Mizoram-Assam border are interdependent on each other for trade and commerce. Mizoram’s bamboo and bamboo products are essential commodities for Assam, and for Mizoram, Assam is a major railhead,” Talukdar explains. “So, when such conflicts happen and the borders are shut for 10 to 15 days, it impacts the lives and economies of both states. Increasing and strengthening interdependencies can act as a measure to resolve this conflict.”

The complex battles at the Mizoram-Assam borders arise from years of colonial extraction of resources in the region, post-independence insurgencies, and a deep dependence of communities on the contested forests, hills, and water bodies within the ILRF. Resolving them clearly demands an equally layered solution.

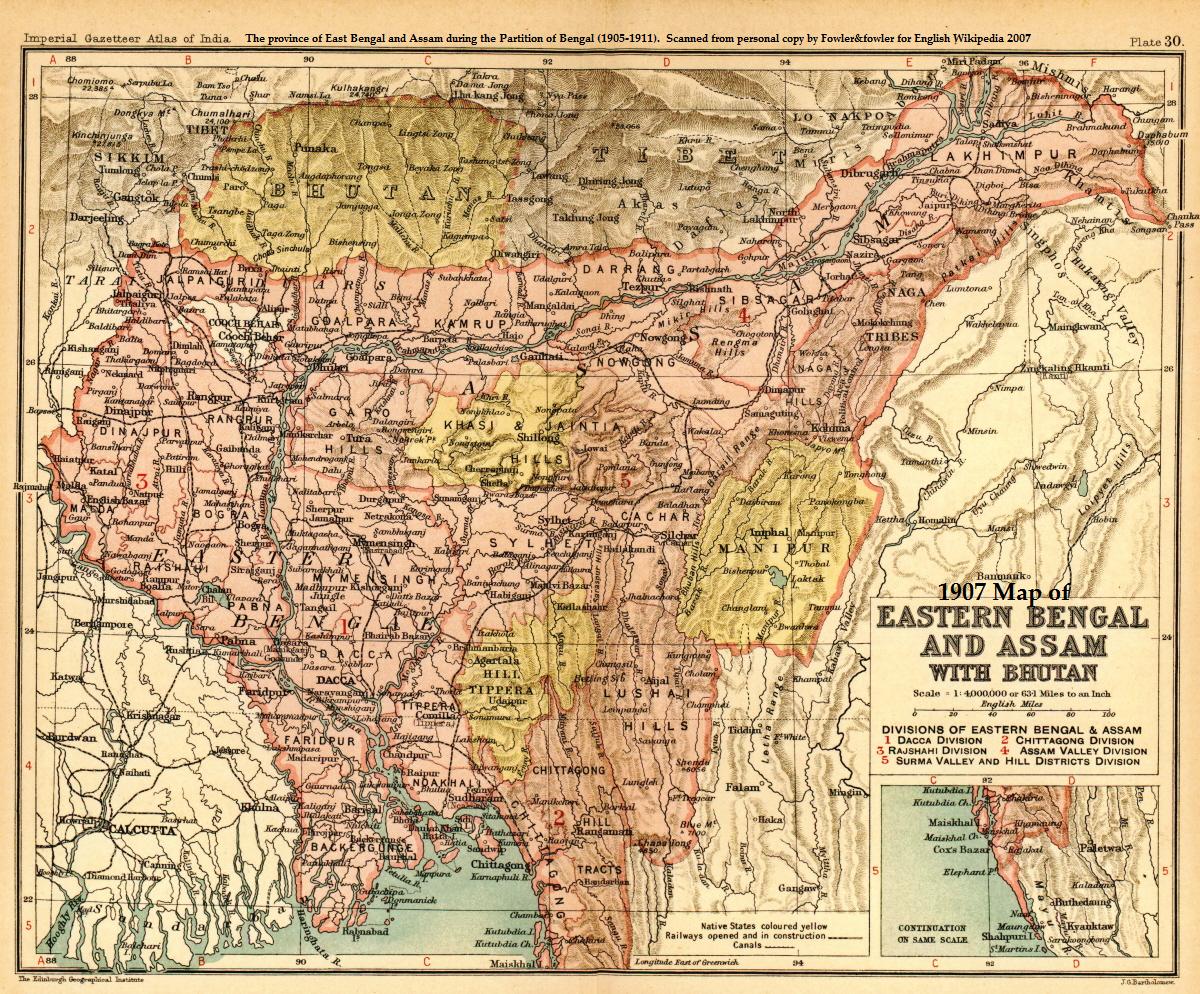

Featured image: a colonial-era map of Assam, Bengal, and Burma (present-day Myanmar) from 1907; courtesy of Oxford University Press.

[1] Map sourced from: Islam, M., Choudhury, P., and Bhattacharjee, P. (2013). Survey and Census of Hoolock Gibbon (Hoolock hoolock) in the Inner-Line Reserve Forest and the Adjoining Areas of Cachar District, Assam, India. Folia Primatologica, 84(3:5), pp. 170-179.

[…] systems in Assam, and 1905 Partition also catalaysed their migration to the region. To support the upcoming tea plantations business, the British brought in labourers from eastern India’s Chota Nagpur plateau—but, they soon […]