Right to clean air stands recognized as part of the right to life and failure to address air pollution is denial of the right to life.

—National Green Tribunal, 2018

Urban air pollution is a serious concern in India. It is a negative externality from a host of sources including construction activities, vehicular exhaust, resuspended dust from vehicular movement, power generation, heavy industry and waste burning. In fact, Indian cities hold the infamous distinction of regularly featuring amongst the most polluted cities in the world. In 2021, 63 Indian cities featured in the top 100 most polluted cities with the Indo-Gangetic plain labelled as the most polluted region. In addition to ecological concerns, high air pollution is reportedly reducing the life expectancy of people in South Asia by 5 years on average, with the reduction reaching as much as 10 years in some parts of the region.

Typically, concerned eyes turn toward the judiciary in India in times of crisis. As this crisis of public bad continues nearly unabated, it is informative to analyze the stance of the principal adjudicator of environmental-related issues in India - the National Green Tribunal. Urban air pollution falls squarely within the domain of the NGT which was constituted under the National Green Tribunal Act in 2010 ‘for the effective and expeditious disposal of cases relating to environment protection’.

This specialized environmental court was established in recognition of the more technical and multidisciplinary nature of environmental issues. For a wider reach across the country, four regional benches have been established across southern, western, central and eastern India, with the Principal Bench in New Delhi also acting as the bench for northern India. The Tribunal is the guardian of environment-related rights enshrined in the constitution and can also invoke the three internationally recognized principles of environmental jurisprudence- sustainable development, precautionary principle, and polluter pays principle, for adjudicating cases (under Section 20 of the NGT Act).

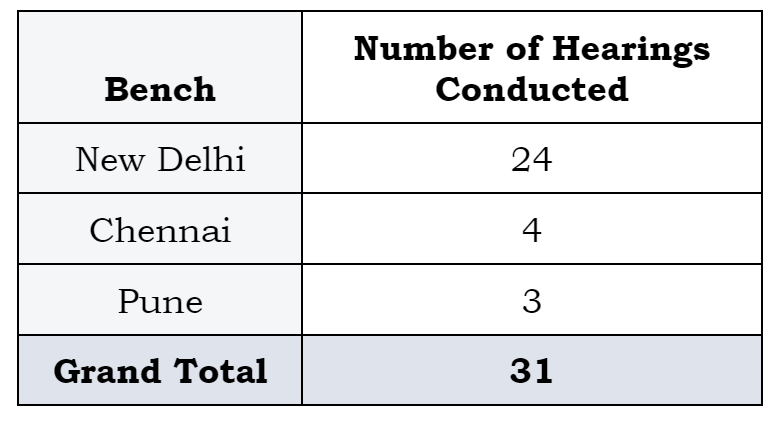

Assessing the trends in urban air pollution-related jurisprudence from the inception of NGT in 2011 to 2020 reveals interesting facts. Using a subset of data from a recent study that analyzes the Tribunal’s judgments related to urban environmental issues, the study draws its conclusions. That study reviews 420 case hearings of which none involved dismissals and procedural adjournments. Amongst these, 31 hearings addressed urban air pollution-related matters which is less than 8% of the total case hearings reviewed. This is far short of the representation of other ‘visible’ domains like waste management and water pollution, which have had over 230 (over 50%) and 130 (over 30%) hearings respectively.

NGT’s Templated Approach

Thirty-one case judgements were reviewed spanning pollution from waste, vehicles and industries between 2011 to 2020. Twenty out of these thirty-one case hearings were for local level pollution-related concerns while eight case hearings addressed issues at the national level. The Tribunal’s intervention in urban air pollution can broadly be classified into two sub-categories. The first category covers cases where the ambient air quality of a region was under question. Air pollution in this case is a result of a host of causes, some specified in the application and some not (‘category 1 cases’). The second category of cases is where a particular activity like waste burning is polluting the air in the local neighbourhood (‘category 2 cases’). It is interesting to examine these categories further as the NGT appears to have developed distinct templates on how to deal with both types of cases.

In 2014, the first case under the aforementioned category 1, Vardhaman Kaushik vs. Union of India, was filed relating to hazardous air quality in the National Capital Region. With orders and judgements spanning 4 years, the NGT issued a slew of directions like the ban on polluting industries and regulating traffic movement, asking the government to develop action plans, calling for specific steps on dust control and waste disposal etc. Finally, in 2018, the Tribunal disposed of the case with a direction to the Central Pollution Control Board for the setting up of a two-member committee to look into the violations of its orders in the case.

Worsening urban air quality across the country saw a suo moto case being taken up in 2018, based on a newspaper (Times of India) article discussing the National Clean Air Programme timelines. It called for 102 ‘Non Attainment Cities’ (i.e. those exceeding average annual concentration levels of notified parameters, like PM2.5, consecutively for 5 years) to take remedial action on air pollution (hereafter referred to as the NCAP case). This case attempted to address issues of urban air pollution across the country and called for the development of detailed carrying capacity studies for each city, steps to tackle vehicular pollution and preparation of action plans under the NCAP by each state and local government.

In both the cases, the Tribunal invoked Article 21 (Right to Life) and the three principles of environmental jurisprudence to chastise the central and the state governments and called for more aggressive action in mitigating air pollution. The two cases have resultantly become the highlight of the Tribunal’s intervention in urban air pollution. Subsequent benches have, ever since, been using the orders in the two cases (in addition to the Supreme Court’s multiple orders in MC Mehta vs Union of India) to address any cases that come before the Tribunal on urban air quality. For example, in Vinay Shivanand Naik vs. State of Karnataka relating to urban air pollution linked to vehicular pollution in Bengaluru, the South Zone bench asked the State Government to comply with action plans formulated under the National Clean Air Plan, as submitted in the NCAP Case. In a similar case, LG Sahadevan vs Union of India, for Chennai, the Bench asked for the preparation of an action plan considering the NGT’s orders in the Vardhaman Kaushik case.

Interestingly, in category 2 cases, the NGT has attempted to directly tackle the specific source of pollution. This is aided by clarity in apportioning the externality with the source. Therefore, in both Jagdish Kumar vs State of Haryana (2020) and Subhas Dutta vs Union of India (2013), which were cases relating to pollution due to improper waste handling, the NGT called for urgent waste remediation steps. Similarly in Nashik Fly Ash Bricks Association vs MOEFCC and Ors. (2014), it asked the Maharashtra state pollution control board and the Ministry of Environment to monitor fly ash pollution levels in Thermal Power Plants near the city. Even in cases filed before, such as LG Sahadevan vs. Union of India (2013), the final verdict came out only in 2022, asking for the action plan under the National Clean Air Programme to be followed.

This approach of templated verdicts on ambient urban air quality-related cases reduces these to mere procedural entries. This fact was also noticed by the Supreme Court in July 2022 with the observation that “Mechanical and pre-drafted orders are being passed by the NGT almost every day”. Further, there is limited evidence of follow-up on orders issued by the NGT. Hence, the onus of ensuring abatement rests squarely on the same organ of government which failed to ensure compliance with existing laws, to begin with.

Limited Reach of the Halls of Justice

There is evidence of a location bias in the hearing of cases by the Tribunal. The Principal bench heard most (24 out of 31) of the cases. Southern and western benches heard only four and three cases respectively. It is to be noted that there have been multiple instances of cases being filed with the Zonal bench but, seemingly due to the non-constitution of a bench at the time, the cases were heard by the Principal Bench.

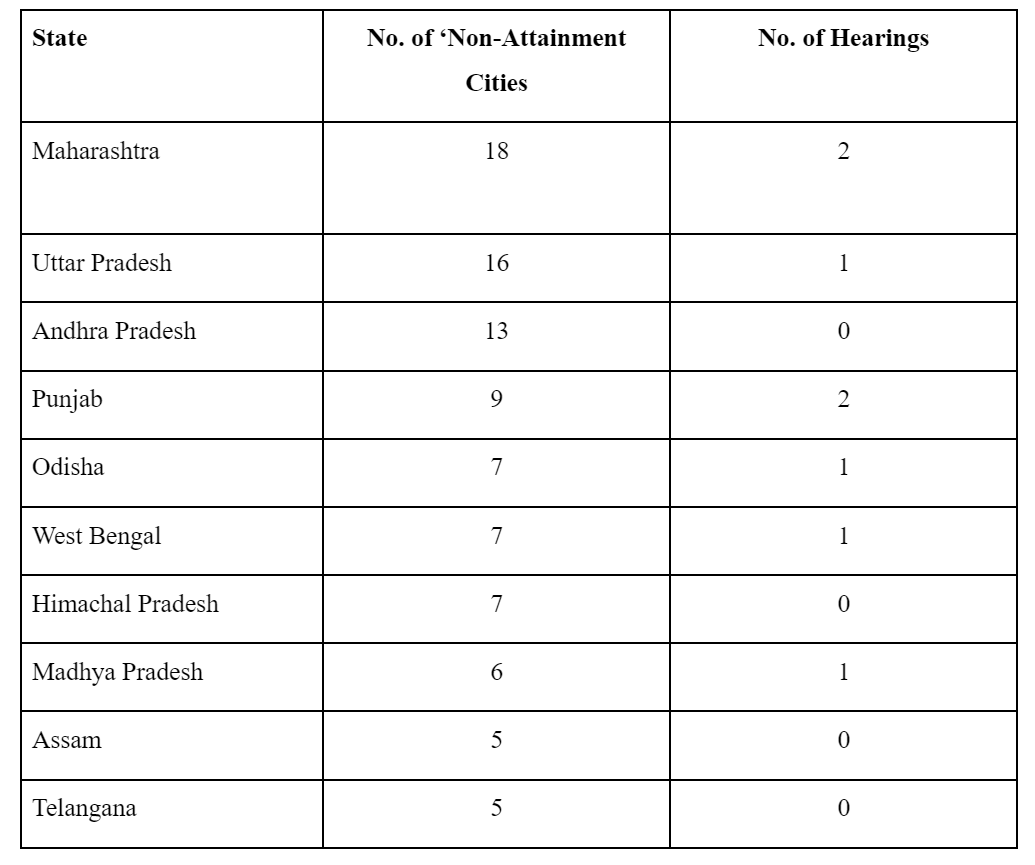

There is also a bias in terms of the states from which the cases have been filed. Illustratively, the cities mentioned as ‘Non-Attainment Cities’, do not have a proportionate share in the cases being heard. Of the three states with the highest number of NACs, Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh (outside NCR) saw 2 and 1 hearings respectively while Andhra saw none.

Apportioning Responsibility and Pitfalls of ‘Templatizing’ Case Approaches

Apportioning Responsibility and Pitfalls of ‘Templatizing’ Case Approaches

Given the continuing state of air quality being recorded in India, it is clear that the government has not been effective in addressing this matter. The Tribunal has often faulted Government departments and particular functionaries for dereliction of duty. In Metro Transit Private Ltd. vs. South Delhi Municipal Corporation and Ors. (2020), it observed,

Response of the Ministry shows apathy and lack of concern which can hardly be appreciated. This Tribunal expects responsible behavior from the officers dealing with the matter which is clearly missing as shown by proceedings of the matter.

Similarly, civil society seems less proactive than expected in reaching out to the judiciary for respite from pollution. An analysis of the plaintiffs at the NGT suggests that civil society is responsible for filing around 47% of the cases. However, in the case of urban air pollution, the plaintiff’s demography seems noticeably different. Only 29% of hearings were conducted on cases filed by civil society. In fact, the most common, about 41%, of the litigants for urban air pollution cases have been affected individuals of localized instances of severe pollution.

The Tribunal grapples with issues of geographic non-representation and wavering activism of the civil society across the domains of case files. However, the Tribunal’s one-size-fits-many approach to urban air pollution-related cases fails to address contextual differences. Air pollution is a wicked problem - interconnected and complex drivers and requires adaptive solutions - and the NGT urgently needs to dig deeper into its repertoire of legal and environmental expertise and more importantly its commitment to fulfilling its role as envisaged.

Featured image of air pollution caused by industries in Mumbai, courtesy Sumaira Abdulali.