In what already seems like a lifetime ago, Delhi was burning. This was before the country went into a lock down in an attempt to slow down the spread of COVID-19. In February of this year, innocent city dwellers were being beaten, lynched, and burnt alive. In a week of deadly violence, 53 lives were lost, more than 200 were injured, while 690 criminal cases were registered leading to 2200 arrests. The injured and dead included not only ordinary citizens, but police and municipal authorities too.

By its very nature, mass violence, much like pandemics, is defined by the relationship between humans and their environment, as well as humans’ relationships with one another. The spatial configurations of the built environment, including the political struggles and power imbalances that produce a particular urban landscape, may intensify these complex relationships. Any post mortem of mass urban violence must therefore carefully dissect where violence intersects with the politics of urban space.

The Delhi Pogrom

The violence occurred in an environment heavily toxified in the run-up to the Delhi Assembly elections. In the days leading up to the violence, a group of women began a sit-in protest against the newly introduced Citizenship (Amendment) Act at the Jaffrabad metro station. This protest, like many others across the country, was inspired by the Shaheen Bagh sit-in, also led by women, which began in December last year.

Yet, unlike similar protests in other parts of the country, the situation rapidly deteriorated in Delhi. On 23rd February, a day before mass violence poured out onto the streets, in Maujpur in North East Delhi, an ultimatum to clear the Shaheen Bagh sit-in was issued by a prominent member of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) Kapil Mishra, to the Delhi Police. The threat, displayed repeatedly on live TV and subsequently shared widely on social media, was that Mishra and his political supporters would otherwise ‘take matters into their own hands’. Interestingly, Mishra has traversed an entire political spectrum having first been expelled from the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP)-who had only a few weeks prior won the assembly elections by a landslide-and later switching political allegiances to the BJP.

What about the neighbourhood?

The triggers of the Delhi pogrom are known. Less has been said about the particular sites and spaces in Delhi and their deeper relationship with the violence that unfolded. It will take a detailed study and some time to unpack these relationships fully.

From today’s vantage point, however, we still need to contend with the basic question of why the violence occurred in some neighbourhoods, and not in others. We also need to question where it occurred, and ask who were the actors (both the protagonists and antagonists) involved.

It is only at the neighbourhood level that it is possible to study how the networks of actors who engage in the organization and instigation of violence are integrated into the social fabric of everyday life. This makes us recognise that violence is mediated by broader geographical and temporal phenomena within the built environment.

The ‘Everyday’ Neighbourhood as a Site of Everyday Violence

Lessons from our research on public violence suggest that the spaces encountered no more than a few minutes from outside one’s home, or on the way to the local market, or while dropping the children off at school, are in fact important vectors along which violence is transmitted, amplified or mitigated. Often ignored as ‘unimportant’ or ‘neutral’ to bigger city-level changes, these neighbourhood spaces provide deep insight into the political struggles relating to both every-day and exceptional circumstances.

That is, these spaces do not exist in isolation, but are part of a particular history and are continually shaped by the movement of people and their struggles to secure a life in the city.

As Gordon McGranahan and colleagues explain, how the city comes to be designed and built “is inherently political and social, as is who and what is allowed or encouraged to come to the city, and who lives and works in its diverse locations, and has access to its diverse amenities. The configuration of the land nexus matters to the city’s economic success, to the wellbeing of its diverse residents, and to those who become a resident or citizen of the city and how they participate in its politics.”

So, seemingly benign urban markers like street lighting, or the way a junction is laid out, or where schools, clinics, shops are situated are themselves products of the politicisation of and contestation over urban space. How can we recognise the production of violence in ‘ordinary’ neighbourhoods though?

Take Ward Berenschot’s exceptional study of two neighbourhoods in Ahmedabad, Gujarat for example. Berenschot showed that the riots in 2002 did not spread uniformly, but were intricately linked with neighbourhood level systems of patronage. He found that the dependence of poorer citizens on politicians to gain access to state resources made poorer neighborhoods more susceptible to political mobilization.

He writes “The dependence of poorer residents on political mediation supplies political actors with local contacts, authority, and influence, which greatly facilitates the mobilization for violence. At the same time, the daily functioning of patronage channels in these areas generates incentives for local actors to collaborate with politicians during riots.” Thus, the neighbourhood is far from ordinary-how it is shaped by the politics of caste and class influence the potential for overt violence to take place in the area.

The history of public violence in Delhi alone provides a lens into these space violence relations: take the 1984 riots as an example. They constituted an unparalleled attack on Sikhs, but at the time, most Delhiites “were content to sit at home and do nothing”[1]. Where were these homes located? The answers tell us how urban space is defined by social markers, making some spaces susceptible to violence, and others, to clear apathy.

The Realities of Living in Violence Prone Areas

In 2012, we studied 45 violence-prone neighbourhoods across urban Maharashtra in detail. We found that households that are economically vulnerable, in the vicinity of a crime-prone area, and are not able to rely on community support, are considerably more prone to suffering from public violence than other households. At the same time, we also found that relatively affluent neighbourhoods, and those characterised by large caste-based fragmentation, are more violence-prone than disfranchised and homogeneous ones.

Interestingly, we also repeatedly found that incidences of mass public violence were not singular or monotone in nature. Instead, they are formed of more complex events where violence is perpetrated at multiple levels, involving more brutal acts as well as minor offences. Sustaining physical injury to one’s person, or damage to one’s property in public violence, is actually rarer than commonly perceived. In our study, only 0.03% of households reported injury or damages to personal property. Interestingly, almost all those who sustained injuries lived within a 5-minute walk of another victim, suggesting a particular space-violence relation.

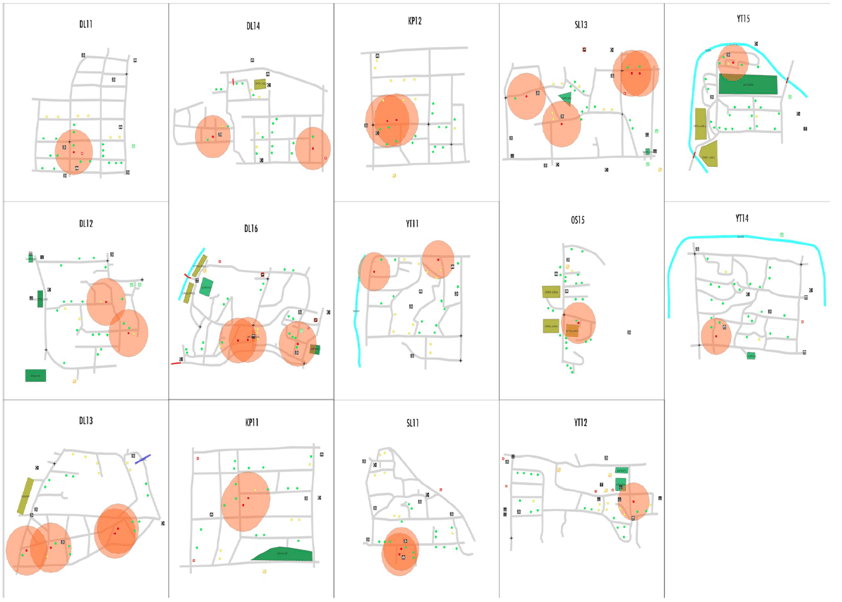

In the adjoining picture, I show this pictorially for 14 of our survey sites. The maps show a variety of spatial data including roads/pathways, waterways, open spaces/gardens, bridges, police stations, schools, markets, clinics and gyms to name a few. Locations of victim households are plotted as red hexagons, and a 2.5-minute perimeter is highlighted in orange around each of them. Overlapping perimeters indicate that victims are within 5-minutes of one another.

Why is all of this relevant to our understanding of the 2020 Delhi riots?

In the days following the 2020 Delhi riots, several heart-wrenching stories emerged of the innocent-a painter returning home, a blacksmith closing his shop, workers who lived above their garment workshop-coming into fatal contact with the violence as a result of their ordinary, even unexceptional interactions in urban space. However, the space-violence relationship, as seen here, speaks to the deeper underpinnings of the city as a system as well as a place to live and work.

If we want to understand the deeper processes that led to mass violence in Northeast Delhi in February, we must not confine our analysis to the macro-political triggers in the days leading up to the violence, or instigations during the violence, though these are important components. We must go beyond looking at everyday lives, and instead look at the seemingly benign processes of production and consumption in the city. We must look at the neighbourhood, not only as the site of violence, but as a real place where people live, work and play; as a place where people’s struggles are as much political as they are social or economic. It is at this level that we must ask why violence erupts in one place and not another.

[1] Kapur, V. 2016. Delhi: 21st Century City. World Literature Today. 90:3-4. Pp. 36-39

Featured image courtesy of Aquib Akhter on Unsplash.