The detection of the COVID-19 hotspot at Tablighi Jamaat at Nizamuddin Markaz in New Delhi led to a surge of Islamophobic expressions in Assam. These spread via inflammatory WhatsApp videos, unverifiable or fake media reports and Facebook images of ‘infected Muslims’ donning skull caps and beards ‘returning’ to the state.

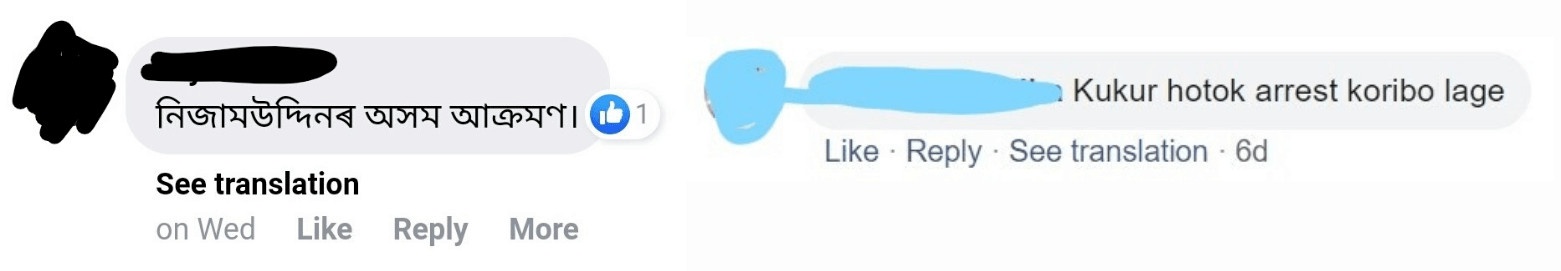

The Muslim community was accused of ‘licking’ currency notes to spread the virus and of ‘attacking’ police and healthcare personnel to avoid treatment. The hashtag #coronajihad also gained prominence across social media platforms in the state. This has spurred more instances of hatred, fear and calls for lethal actions (such as shoot to kill) against these ‘diseased’ Muslims in order to ‘save’ Assam.

Islamophobia has been recognized as “a type of racism that targets expressions of Muslimness or perceived Muslimness”. Besides lay citizens’ forwards, tweets from ministers in the BJP-led Assam government using #NizamuddinMarkaz to isolate primary and secondary infections and TV channels’ disclosure of the names of those infected Muslims gave legitimacy to fears about Muslims’ attack on the ‘integrity’ and ‘safety’ of Assamese people.

Alert ~ 8 more #COVID19 positive cases in Assam, taking the total to 13.

All eight new cases are of people who also participated in #TablighiJamaat congregation at #NizamuddinMarkaz.

Update at 9 pm / April 1

— Himanta Biswa Sarma (@himantabiswa) April 1, 2020

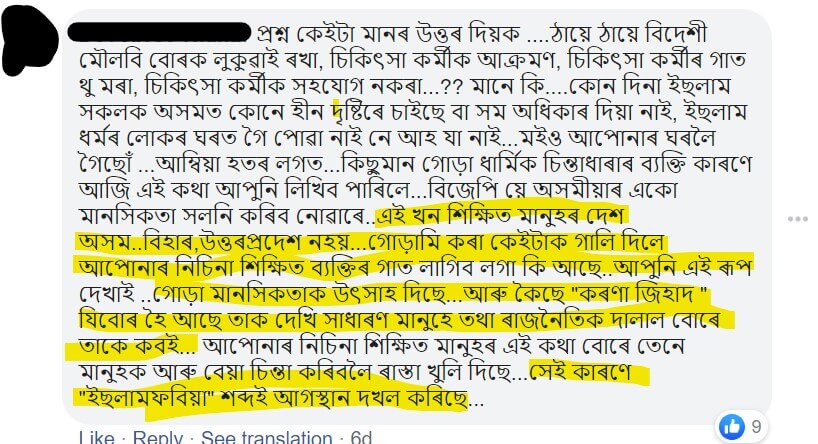

At the same time, ‘educated’ Assamese Muslims began publicly denouncing the actions of the ‘diseased’ ‘jihadi’ Muslims. Anyone who pointed out the blatant loathing and fear expressed towards the Muslim community would themselves be looked at as being responsible for the growth of ‘corona jihad’. This way, the Muslim community in Assam has been construed to be complicit by harbouring ‘fundamentalist’ intent themselves, as the following Facebook comment indicates.

Media platforms have consciously furthered certain cues of ‘Muslimness’ to perpetuate such hatred; attacks are particularly targeted at those who follow a more religious life, which is portrayed through their attire (burqa, head-scarf and skull caps), praying rituals and participation in prayer meets. This is presented in contrast to those who profess a more ‘progressive’ lifestyle of Islam — one which is devoid of ritualistic religious symbolism and practices. These ‘progressive’ Muslims find it easier to assimilate into Assamese society. In this way, Islamophobia can be understood in a nuanced manner beyond just a binary expression of hatred towards Muslims. The case of Assam exposes the contexts wherein Islamophobia thrives and the socio-economic dynamics that shape it.

Constructing ‘Progressive’ and ‘Conservative’ Muslims via Electronic Media

After many returning participants at the Zamaat were detected in Assam, popular TV news channels held debates and invited Maulvis and ‘progressive’ Assamese-Muslims to discuss the crisis ‘brought on’ by infected Muslims. Let’s look at a discussion between the eminent Assamese writer and researcher Ismail Hussain, who was one of the guests on a show titled “Why Progressive Muslim Fight the Tablighis of Assam”, on Pratidin Times, a leading Assamese TV news-channel.

The host Mrinal Talukdar opened the discussion by calling all viewers to imagine “the picture of the oasis, Assam, [which] has changed because of one incident, which will not be forgiven ever…yesterday we had 16 [cases of infections], tomorrow how many, who knows, calculate yourselves”. He openly accused those who participated in the Zamaat as “Maulabadi” (fundamentalist). Mr Talukdar then reminded Mr Hussain of the “impact” of the “reality of the conservative, fundamentalist [Islamic] ways of living has on the image of moderate, educated Muslims”.

After a long response about the ‘problems’ of Islam and his different position as a “progressive” Assamese-Muslim, Mr Islam added that “these people do not have any progressive thinking. These people talk about the prohibition of drugs, alcohol, the importance of cleanliness and hygiene, pray five times a day… but they will not talk about population control, modern education, the just use of time and women’s empowerment…they leave their own families for religious congress…Their first job should be to protect their own homes and society…They pushed our state into a dangerous situation, we are very ashamed and unhappy about that”. Mr Islam also pointed to the continued efforts, and failures, of the Assamese-Muslim society, including himself, in educating “these” people, especially those living in Lower Assam and Char-Chaporis (riverine sand-bar regions of Brahmaputra valley) of Assam.

I chose this particular show because it offers insight into how Islamophobic experiences are not the same for all Muslims in Assam. Notwithstanding the fact that any large-scale gatherings must be avoided during the pandemic, these attacks are couched comfortably within discourses of modernity, education and religious practices — clearly targeted disproportionately at the lowest rung of Muslims and the general Assamese society. For example, Muslims living in Char-Chaporis face cascading risks of environmental degradation from yearly flooding and soil erosion as well as economic risks of poverty and a lack of educational and healthcare facilities, to name a few. These people are also often marked as ‘illegal migrants’ and thus as ‘outsiders’ in their state [1].

Clearly, narratives and experiences of Islamophobia are deeply intertwined with other forms of inequalities. Those in positions of power and influence (read: media, politicians) act as paraphernalia and are integral to its violent reproduction. Mrinal Talukdar carefully constructed the ‘dangerous’ and ‘diseased’ Muslim with the help of a powerful, well-off Assamese-Muslim’s ‘knowledge’ on the ‘problem’. In this way, eliminating the diseased (and racialised) bodies becomes a duty of the dominant, disease-free and ‘progressive’ Muslims.

Nuanced Islamophobia, Widespread Damage

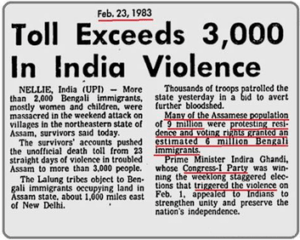

Constituting about 34% of the state’s population, there are popular references to religious harmony and cultural intermingling that show how Muslims have always been an integral part of Assamese society. On the other hand, the community has also been relegated to a secondary position in historical manuscripts like the Buranjis, which date back to the 13th century CE. With the NRC of Assam, many Muslim communities, especially the Bengali Muslims (popularly known as Miyas) are still targets of communal politics and violence.

From this false binary comes a second issue: the intentional misrepresentation of these diseased Muslim bodies as biological threats, which creates a belief that they are not equally deserving of healthcare and treatment. These constructions have the potential to instigate and justify physical violence against suspected/identified Muslims.

Third, a pandemic which affects every Indian citizen has been constructed as an ‘external’ import, as if racialised bodies are invading Assam and ‘threatening’ its society’s integrity. These narratives divert the attention from the State’s responsibility of handling the pandemic with care to a communal non-problem. This falls nicely into the laps of the ruling right-wing party that castigates all who do not subscribe to their ideological paradigm.

Fueled by unethical media platforms, Islamophobic discourse in Assam exposes how age-old binaries of ‘good’ or ‘acceptable’ Muslims are pitted against ‘bad’ or ‘unacceptable’ Muslims. Focusing on their religious practices or ‘Muslimness’, alongside their history of (non)assimilation has left a long-lasting impact on how certain Muslim communities access healthcare, receive financial support and continue their overall fight against the global pandemic.

[1] Saikia, Y. (2017). The Muslims of Assam: Present/Absent History. Cambridge University Press, pp. 111-134.

[2] Borooah, V. (2012). The Killing Fields of Assam: The Myth and Reality of Its Muslim Immigration, Economic and Political Weekly, 48(4), pp. 43-52.