In an opinion article titled “Busting myths and the double-speak on education” published in the Hindustan Times on July 07th, 2020, Mr Gurcharan Das raises some important points about the state of public and private education in India. He writes in favour of having an Indian education system wherein privately-provided education can proliferate freely, that too at “one-third the cost of government schools”. Mr Das is confident that private schools can deliver better outcomes for Indian students en masse.

The private school sector is growing at a massive pace. Nearly 50% of India’s children attend private schools, and we need to provide the sector more autonomy if we want improved learning outcomes for them. My piece in @httweets https://t.co/2jrXCE1Xgp #StateOfPrivateSchools

— Gurcharan Das (@gurcharandas) July 13, 2020

While it is heartening to see comments on education at a time dominated by discussions on healthcare, these tall claims made by an eminent scholar warrant a deeper examination to understand how well they hold up at the ground level. My sole intention through this piece is to make an honest case for strengthening India’s public school system, and I trust it will be received in that light.

>85% of students are enrolled in state-run schools in developed countries, India stands at ~55%

Let’s begin with Mr Das’ quote on ‘developed countries’:

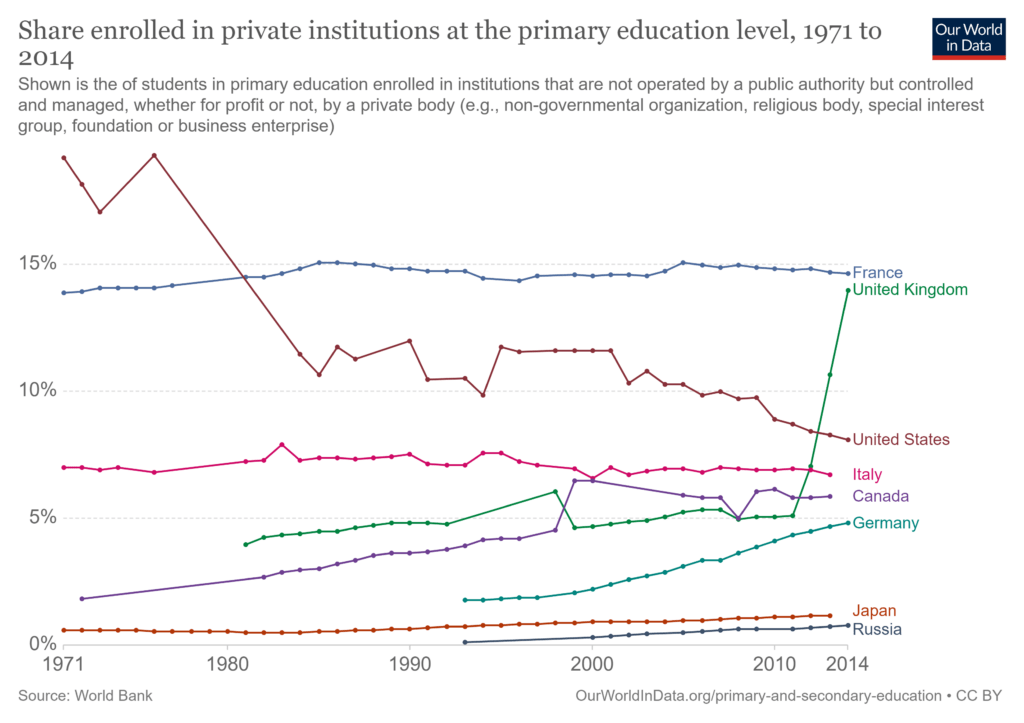

Unfortunately, he has conveniently left out the data that will help readers understand the exact extent of this ‘encouragement’. Take a look at the chart below.

Despite the recent steep increase in the UK, we see that the overall share of students enrolled in private schools hovers between 5 to 15 percent within the erstwhile G8 countries. Besides this share being relatively stable across the last fifty years, the US actually shows an active dip in its percentage, contrary to Mr Das’ assertion. There is certainly no myth in stating that education at the school level is largely provided by the State in developed countries.

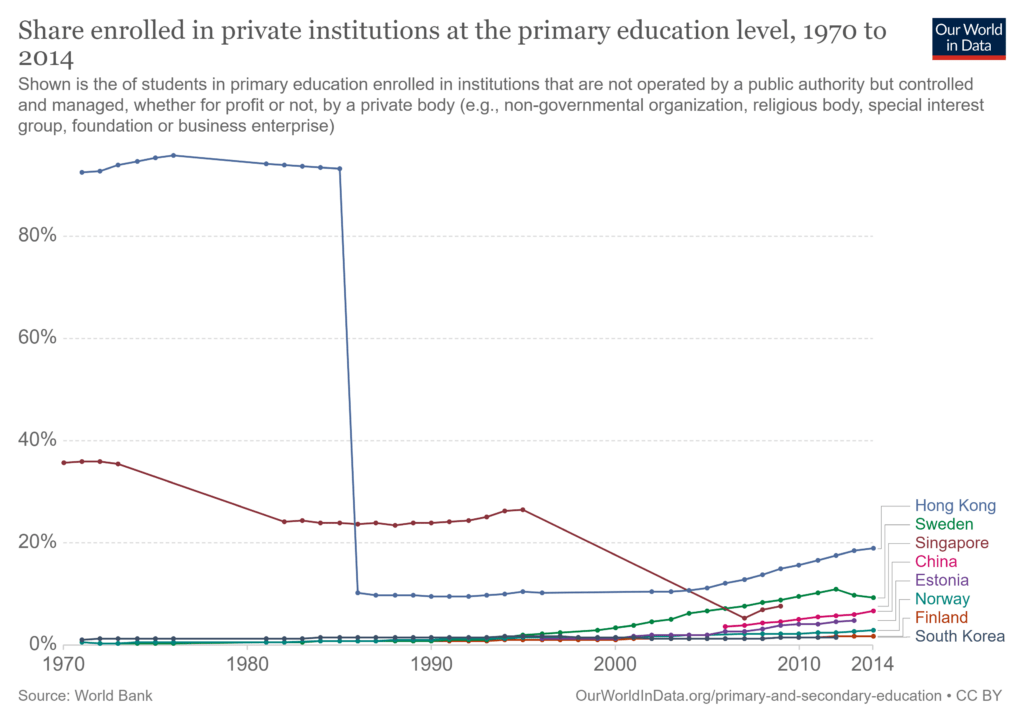

Now, what about the Scandinavian and other countries that have fared excellently on the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), which assesses reading, math, and science amongst 15-year olds?

The Scandinavian countries also plateau at 15 percent. In fact, Singapore (the line in maroon), a country that has consistently placed at the top of PISA, has significantly brought down its share of private enrolment!

As of 2018, 45 per cent of Indian students were already enrolled in private schools between grades 1 to 12. Then why is there a clamour for more private schools? We are already way ahead of that curve; despite Mr Das’ claim of ‘encouragement to privatisation in developed countries’, these figures cannot be contested.

We are Grossly Underspending on Education by 50%

Now let’s move on to examine Mr Das’ point about India’s “huge investments in government schools”:

India used to spend 17 percent of its public expenditure on (all levels of) education back in 1999. This figure has dropped down to 10.6 percent in 2018-19, while the global average for the same stood at 14.5 percent. Where India’s budgetary allocation towards education has hovered between 2-4 percent of its GDP for the last 30 years (ranking 149/197), the global average lies around 4.7 percent. There has not been any significant change in investment in government schools, as Mr Das has suggested. In fact, we are spending less than we ought to and significantly lesser than the ‘6 percent of GDP’ figure that was recommended by the 1946-66 Kothari Commission. India is also spending less than the ‘4 to 6 percent of GDP’ and ‘20 percent of government expenditure’ that were recommended repeatedly by UNESCO in order to meet the SDGs.

‘Low-cost’ Private Schools Operate by Exploiting Teachers

He raises some important points about cost:

An interview with a government primary teacher in Uttar Pradesh revealed that the Grade Pay is ₹4200 and Basic Pay is ₹35,400; with a Dearness Allowance of 10% and House Rent Allowances between 18-20%, the salary comes up to ~₹42,000. Upon deducting the Statutory Provident Fund, the salary received in-hand would be ~₹37,500, which is the same for new joinees as well. In Maharashtra, earning a full salary requires a three-year probation period with stipends that are below ₹10,000 per month.

Let alone the starting salary of a junior teacher, only teachers on the verge of retirement may bring in the ~₹48,000 figures that Mr Das has cited. But let’s say these teachers were earning ₹48,918. If private school management and owners should be allowed to make profits off of providing education, as Mr Das opines, then what is wrong in the government paying a professional teacher who is providing an essential service to our children? Why the outrage?

The Center For Global Development cites research which finds that “investing significantly more money to train, recruit, and retain the highest quality teachers in public education systems is even better value for money”.

The discussion on ‘how much is too much’ with regard to compensating quality teachers in India goes beyond the scope of this article.

Having said that, a majority of the ‘low-cost private schools’, which are mostly concentrated in urban areas, have extremely below-par pay scales for teachers. These teachers come from humble backgrounds with poor qualifications; they have little bargaining power with school management and have had to resign themselves to an average income of ₹4000 per month. My time spent working in such schools showed how worrying human resource practices like delayed payments, denying leaves, placing admission targets and many others can border on the exploitation of labour. This is the secret sauce behind the low-cost in ‘affordable private schools’. This gets easily overlooked when we undertake shallow cost-benefit analyses.

No significant difference in learning outcomes when income and social background are controlled for

Outcomes matter immensely, especially when it comes to learning. Repeated scientific studies and meta-analyses of data from different countries have shown that while on average, private schools tend to be marginally better in certain contexts, there is no significant difference between the two once the students’ household income and social background are controlled for. Delhi remains a beacon of hope for progressively better outcomes that are a product of investing heavily in public schools.

Over the past 5 years, we at #DelhiGovtSchools have been competing with ourselves to break our own record each time. This year is no exception!

2020: 98%

2019: 94.24%

2018: 90.6 %

2017: 88.2%

2016: 85.9%Congrats to students, parents & Team Education! https://t.co/ktNogcLZEW

— Manish Sisodia (@msisodia) July 13, 2020

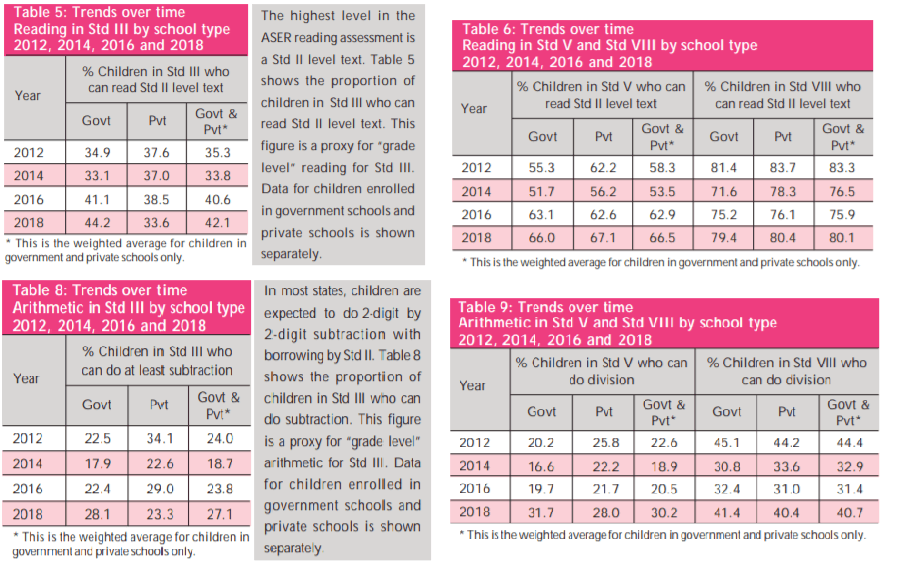

The 2018 ASER report in Maharashtra found that government school-going children can subtract and divide better than private school-going children across all grades. Government schools outperformed private schools by 11 percentage points in terms of reading in grade 3. For grades 5 and 8, the scores for reading were almost equal; the difference in percentage points was in single digits.

These reports indicate that both learning outcomes are quite abysmal, in both private and publicly-run schools. Moreover, regardless of which type of school one attends, a poor student or one from a marginalised background is likely to fare worse than their peers. The central problem facing education is one of quality and equity, which cannot be solved simply by allowing private schools to proliferate, as Mr Das would have us believe.

COVID-19 Will Discourage Masses from Paying for School

Now let’s move on to the point about public schools emptying out, especially in the times we currently find ourselves in. Indeed, more families have opted for private schools over the past decade. However, the coronavirus pandemic has caused a 50 to 70 percent loss in income for those on the brink of poverty. An ILO-backed survey states that 80 percent of urban jobs and 54 percent of rural jobs have been impacted.

If you were from one of these families and were given the choice between free education or paying ₹500 to ₹1000 as fees every month, which one would you choose? Consequently, which schools do you think we should concentrate our efforts to improve?

The answer seems apparent if one goes by the news reports that cite the closure of some low-cost private schools and the inability of others to pay their teachers during the pandemic.

Let us not forget that besides tuition fees, private schools charge for transport, books, and uniform — all of which are free in government schools. According to an FSG report, 80 percent of affordable private schools (APS) are already making an operational surplus; successful APSs can make profits over ₹10.5 lakhs a year. It makes me wonder what new dawn Mr Das is expecting to be ushered into when he writes that “this single change from a non-profit to profit sector could create a revolution”. Besides, where does one draw the line at profit-making?

It is an ethical travesty to look the other way when the truth is that a family’s ‘ability to pay’ decides whether their children have access to quality education. Well-administered public schools with a progressive taxation model can subsidize the costs for the poor (which is the case in most developed countries) and is the equitable way of securing every child’s fundamental right to receive a quality education.

In Conclusion: Let’s focus on high-quality public schools, shall we?

As the cliché goes, different contexts require different solutions. 60 percent of Indians live on an average monthly income of ₹10,000; instead of channeling all our efforts towards increasing the quality of the free option, championing the scaling of a fee-paying option is absurd. Mr Das’ well-intended arguments are untenable when we consider India’s constitutional mandate and developmental goals. No “honest entrepreneur” from his imagination has ever gone to a Nandurbar or Gadchiroli (or most rural and tribal areas) to open a for-profit private school. So what happens to the children there? Relegated to negligence, as they have always been?

In the interest of our children, their teachers, and the livelihoods that are dependent on quality education in a post-pandemic era, strong calls must be made to politicians and policymakers for strengthening public schools that can cater to all citizens. Resilient public institutions are the backbone of a socially equitable and economically developed India, and well-functioning government schools are the need of the hour. Instead of weakening them through pro-privatisation policy or making misleading arguments about ‘competition’ and ‘choice’, let us come together and direct our attention, energy, and efforts towards truly making quality education free for all.

PS: In case Mr Das is tired of the License Raj, I would heartily like to extend an invitation to him to visit Maharashtra, where the standard waiting time for a self-financed school is not more than 6 months.

Views expressed are personal | Featured image courtesy Leadership for Equity, taken by Symbiosis School of Communication

This is so insightful, thoughtfully argued, and heartfelt. Thank you for authoring this, Siddesh.

I agree with the article when it comes to raising the standards for government schools in order to create an equitable society. Children in low-income rural areas are either forced to go to an abysmal government school or their parents scrimp and save to send their kid to a private school. I have seen that the notion of parents is that government schools are ridiculed with problems and their children will not get the attention they need. Therefore they send their child to a private school with the hope of getting a better education. My contention with your article is that you did not adequately address the point of Mr. Das that it is unnecessarily cumbersome to start a private school in India. While the Delhi government is doing amazingly well in creating quality schools, its still a hassle for someone who is well-intentioned to start a private school in Delhi. https://ccs.in/licenses-open-school-it-s-all-about-money. Easing of the hassles of starting a school can foster a innovation in terms of pedagogy and curriculum. Ideas of what it means to be educated are varied and it should be. Different schools of thought on education can proliferate if the type of schools that we can set up across India is varied. These schools can cater to the different sections of society according to what the parent or the child wants. Again, I’m not saying government school should be neglected. They should be strengthened for an equitable society.

I would strongly recommend the book “Shiksha” by Manish Sisodia,

published by Penguin, to Mr Gurcharan Das.

In India, the governments would do well to increase ‘investments’ in public schools, as well as diversify curriculum to suit needs in different areas, offering subject choices relevant to the needs of the society. In that aspect the public schools would be at the forefront of educational standards.

Also, from your article there seems to be a step up of performance of public schools in 2016 & 2018 in Maharashtra. The steps taken by the education board for the improvement should be replicated with increasing the ‘prestige’ associated with public schooling. Currently, despite financial strains, the parents believe that going private is somehow better. articles like that of Gurcharan Das can further mislead parents.

Ver insightful and well researched article with balanced and unbiased views. Thanks for bringing this to us, Siddhesh, and look forward to more.

Thanks Sonal. Glad you found it helpful!