When asking a non-migrant fisherman in Odisha’s Nua Golabandha about why so many fishers choose to migrate across the country, this is what he had to say. “Here they can earn one lakh per year, whereas, in the other states, they can earn one to two lakhs in three to four months.”

With the recent migrant crisis precipitated by the COVID-19 lockdown, we have read and heard a lot about migrant workers in all spheres, including the fishing sector. While migration in India is always complex-as per the 2011 census, around 37% of India’s population, or 450 million people, migrate for work within the country alone-the fishing sector’s history with migration is unique. Historically, many traditional fishing communities in India have engaged in complex migration patterns that involve shifts in both location, occupation, and incomes.

The seasonal nature of fishing leaves marine fishers unemployed for parts of the year, making it necessary to seek alternative employment during the lean season. In simple terms, migration for fishers is a generational response to this occupational uncertainty.

The proportion of migratory shifts is determined by various factors including the skills and aptitude of the fishers, availability of opportunities, caste and kinship ties, shared bonds of language and geography, political and religious forces, and traditional access or use rights to the coastal commons.

Take the case of Srikakulam, in Andhra Pradesh, from where a majority of India’s migrant fishers hail. With a total population of 27,03,114, as of 2010, Srikakulam was home to 128 marine fishing villages, and 25,579 fishermen families; out of these, a staggering 25,295 lived below the poverty line.

For generations, this community has sought better fortunes both abroad and within India. As per data collected by Venkatesh Salagrama, in 2002-03, the active fishermen population in Srikakulam district was 25,582. Of these, 56% of fishers migrated for work.

The migration streams of fishers from Srikakulam district provide valuable insights into the larger history of fisher migration in India, and the social, political, and policy shifts that motivated them. As we look towards strengthening India’s fisheries under the Pradhan Mantri Matsya Sampada Yojana, lessons from Srikakulam’s past shed light on how communities need to be supported in the future.

The First Exodus: From Srikakulam to Burma

Salagrama and Sarma (2004) categorize the streams of fisher migration from Srikakulam over the last 150 years into three waves. These streams are a result of various ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors.

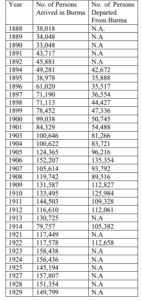

The first wave is believed to have taken place between the latter half of the 19th century, and continued up to World War II. Fishermen from Srikakulam were pushed to migrate by various factors, such as poverty, unemployment, adverse seasonal conditions, natural calamities, and famines. Their destinations: Burma and Malaya, or present-day Myanmar, and Singapore and Malaysia respectively.

Fishworkers were pulled to Southeast Asia in the 1870s by the increasing demand for manual labour in these newly industrializing British territories, as well as the growth of transport and communication facilities between the regions and the east coast of India.

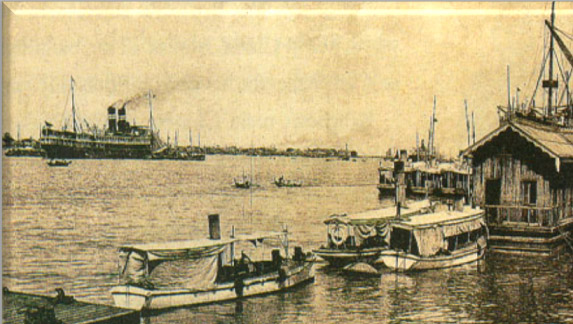

So, when a British-India fortnightly steamer service was introduced, connecting Kakinada, Visakhapatnam, Gopalpur, and Rangoon, the peoples of coastal Andhra familiarised themselves with Burma like never before.

More importantly, migration was also undertaken mainly by lower castes, who sought equality and emancipation overseas. In traditional fishing castes like the Vadabalijas, taking up other occupations is still looked down upon. Nevertheless, with the distance and weakening of social and caste constraints, fishers moved into many different occupations in Burma. While this migration was mainly seasonal and cyclical, there were also long term migrants too, who stayed in Burma for a year or two, and then returned home with a fair amount of savings.

S Ramayya Rao, the father of 78-year-old S. Govind Rao of Ganjam, was one of the many fishermen who migrated to Burma. “My father worked in the Rangoon port, loading and unloading cargo from ships. My grandfather, uncles and many others from my village went to Burma too, as there was no work in the village. They had good facilities there.” And so, the pioneer migrants, successfully made their fortunes in these new lands, eventually persuading others to follow. Some women also followed, but in lesser numbers. Women mainly migrated to Burma as sex workers or domestic servants. After earning a significant amount abroad, they would return back to their villages.

During this wave of migration, fishing was still a viable occupation and provided enough income to survive-this changed with the onset of World War II. As Japanese forces advanced through Burma in 1942, a significant number of Indian migrants fled the country through land routes. Many were killed or died on the way. Govind Rao recalls, “When Japan invaded Burma during the war, our workers were asked to leave. They walked all the way back [to Andhra Pradesh], through Manipur. Some had to carry their children. They didn’t have any food.”

Migration Post-Independence: Finding New Homes Across the Country

While the second wave mostly took place between 1950 and the mid-1970s, it began during World War II.

When the migrants returned home from Burma, the situation on the east coast had worsened due to the war. This was the period of the Great Bengal Famine and even the bare necessities were hard to come by. Fish catches were also poor as the fishers could not venture out far due to the presence of the Axis forces at sea.

A combination of these factors led to starvation in the fishing villages. As the repatriates had lost touch with fishing, they travelled long distances in search of employment. A huge population from the fishing villages migrated during this wave, mostly finding work in urban areas such as Visakhapatnam, Vijayawada, Kolkata, and Cuttack. Many of them took up manual labour, construction work, rickshaw-pulling, and head-loading. The caste constraints of traditional fishing populations were no longer a factor-as work was now a question of their very survival. While some returned to their villages after the war subsided, many chose to stay on wherever work opportunities were available.

During this period of exploring employment opportunities in the early 1950s, some migrants found employment in Gujarat’s Kandla port, while others entered the state’s wood and welding industries. Another destination was Assam, where work in the plantations, coal mines, and railways was available. Between 1960-70, fishers migrated to Bhilai to work in the steel industry, to Raipur to work in the railways, and to Kolkata to work as cleaners. Joining the Merchant Navy was also popular. And so, as the country gained independence, new migration routes for the migrant fishers of Srikakulam were forged.

The Andaman Islands were another important migration destination from the early 1970s onwards. The government provided incentives of free accommodation to Srikakulam’s fishers to settle in the islands to improve the fisheries there. They were also provided with boats, fishing gear, and working capital. Many moved to the Andamans permanently with their families in tow.

Of all the migration routes, this was the most lucrative for fishers as they remained in their vocation and owned their fleets too, besides earning other perks.

During this wave, migrants largely settled in their various destinations and returned to Srikakulam only as visitors; this trend continues today. A fish trader Rama Rao, of Andhra origins but born in South Andaman opines, “Prior to the 2004 Tsunami, there were only about 500 fishing families living in Junglighat Machchi Basti, here in South Andaman. But now, every month around ten families come here from Andhra. Out of those ten families, nine eventually settle here. Very few fishermen come for 6-8 months and then go back [to the mainland].”

Srikakulam witnessed Naxalite uprisings in the late 1960s and early 1970s due to poor development, and the exploitation of fisher communities and local Adivasi populations. After the uprisings, between the 1970-80s, the district received some infrastructural growth, which was perhaps bolstered by the modernisation of the fishing sector.

Since the 1960s, the fishing sector on the east coast had begun to ‘modernise’, shifting to motorised boats, gill-nets, and trammel nets. During this period-also known as the ‘pink gold rush’ because of the high volume of shrimp exported globally markets-the push factors to migrate were almost negligible due to better catches and income.

And so, the fishing sector moved from subsistence fishing to commercialized fisheries. New crafts, gear, nets, and costs also made the sector more capital intensive, bringing different players like traders and moneylenders into the picture.

The emergence of a new entrepreneurial fishing class meant better education and lives for their families. Yet, for those left behind, the story was different. There was an evident increase in inequality as a result of the ‘modernization’ and commercialization of the fisheries.

Development for Whom?

The third wave of migration started in the mid-1980s and continues with much vigour even today, with the main destinations being Gujarat, Maharashtra, Goa, and Karnataka.

Salagrama and Sarma (2004) observe that during this phase the push factors are stronger than in previous periods. The main push factors are reduced access to natural resources and coastal commons (like fish, sea beaches, water bodies, and coastal vegetation), increasing production costs, debt, and uncertainties related to marketing.

“People buy fishing boats by borrowing money. The boats usually cost 5-6 lakhs. Sometimes, they even sell for up to 10 lakhs. If they are lucky, they can earn and repay the debt. Or else, they sell the boat and migrate to other places to repay the loan,” says P. Korliah, a fisher who migrates to Mangalore harbour for work for ten months every year.

These factors can be attributed to the inappropriate development of goals and policies currently facilitating the commercialization of the sector. Despite significant investment in physical infrastructure, there was little focus or intent to build the capacities of small-scale fishers, empower them, or include them in the decision-making processes that would shape their lives and livelihoods.

You May Also Like: PM-MSY’s Fisheries Development Promises Anything But Sabka Vikas

Technological advancements increased the fish catch for a few decades, as seen during the second wave. However, the repercussions of these advancements became evident from the 1980s onwards, as the capacity of natural ecosystems to recover was not considered. Fishermen noticed a reduction in catches of commercially important species like pomfrets, seer, and shrimp and the complete disappearance of a few local species like catfish, wolf-herring, and sawfish.

With the increasing cost of fishing, fishers now had to harvest more in order to retain the same margins. The dependence on inputs, traders, and export markets made the fishers more vulnerable and reduced the resilience of fishing as a livelihood. By focusing on a few commercially important species, people’s access to cheap fish also reduced, which in turn led to a decrease in food security.

There were definitely pull factors too, the most important being the fixed wages in the mechanized fishing sector in states like Gujarat. In Andhra Pradesh and Odisha, fishers are paid a share of the catch instead of fixed wages, which is why they choose to work in the harbours of the west coast. As newer generations of fishers view artisanal fishing as old fashioned, the allure of the technological advancement in the mechanized sector only increases.

Lessons from History for Informed Policymaking

The history of migration from the fishing villages of Srikakulam in the last century and a half bestow us with many lessons.

The first wave showed that migration to Burma gave fishers an opportunity to increase their income and move beyond the uncertainties associated with fishing as an occupation. The second wave revealed the realities of extreme poverty and what unchecked ‘modernization’ in fisheries could do. The third wave showed us the unequal after-effects of commercialization, inaccessible coastal commons, and poor environmental democracy. A focus on few commercially important fish species led to the decline of their catches and also, the availability of cheap fish for local consumption.

All these niggling factors over the years have pushed fishers from Srikakulam further and further away from their homes; in some cases, this has empowered them, and in others, has made them very vulnerable. The role of caste and kinship ties in providing the migrants with critical opportunities throughout the country-and not necessarily policies-cannot be underestimated in this atmosphere of occupational uncertainty.

All of this adds up to a simple axiom: the journeys fishers made from Srikakulam shows that migration in fishing communities is not a new phenomenon and will continue until there is a paradigm shift in the fisheries sector in India. And so, if we are to frame policies regarding fisheries or the ‘development’ of fishing villages, large-scale migration and the reasons behind it need to be considered too.

For more on coastal India’s past, present, and future, curated by The Bastion and Dakshin Foundation under “The Shore Scene”, click here.

Views expressed are personal | Featured image courtesy of Bipro Behera.

[…] by Madhuri Mondal on how fishworkers have migrated in the past, and migrate in the present. Click here to read part one, on how and why Srikakulam’s fishers spread from Myanmar to Gujarat in colonial and newly […]